Tag Archives: algorithm

Imagine the watershed for a river. Every drop of water that falls in that area, if it doesn’t evaporate or sink into the ground, eventually makes its way, through creeks, streams, and rivers, to the lake or ocean that is the shed’s final destination. The visual image is somewhat like the veins in a leaf. Or the branches of the leaf’s tree.

Imagine the watershed for a river. Every drop of water that falls in that area, if it doesn’t evaporate or sink into the ground, eventually makes its way, through creeks, streams, and rivers, to the lake or ocean that is the shed’s final destination. The visual image is somewhat like the veins in a leaf. Or the branches of the leaf’s tree.

In all cases, there is a natural flow through channels sculpted over time by physical forces. Water always flows downhill, and it erodes what it flows past, so gravity, time, and the resistance of rock and dirt, sculpt the watershed.

The question is whether the water “computes.”

Continue reading

16 Comments | tags: algorithm, computation, computationalism, computer code, computer model, computer program, consciousness, full-adder, Theory of Consciousness, theory of mind, Turing Machine | posted in Computers, Philosophy, Science

Previously, I wrote that I’m skeptical of interpretation as an analytic tool. In physical reality, generally speaking, I think there is a single correct interpretation (more of a true account than an interpretation). Every other interpretation is a fiction, usually made obvious by complexity and entropy.

Previously, I wrote that I’m skeptical of interpretation as an analytic tool. In physical reality, generally speaking, I think there is a single correct interpretation (more of a true account than an interpretation). Every other interpretation is a fiction, usually made obvious by complexity and entropy.

I recently encountered an argument for interpretation that involved the truth table for the Boolean logical AND being seen — if one inverts the interpretation of all the values — as the truth table for the logical OR.

It turns out to be a tautology. A logical AND mirrors a logical OR.

Continue reading

9 Comments | tags: algorithm, AND gate, boolean logic, computation, computationalism, consciousness, human consciousness, interpretation, logic gate, NAND gate, NOR gate, OR gate, Theory of Consciousness, theory of mind, truth table | posted in Computers, Math, Philosophy

Back at the start of March Mathness I promised the math would be “fun” (really!), but anyone would be forgiven for thinking the previous two posts about Special Relativity weren’t all that much “fun.” (I really enjoy stuff like that, so it’s fun for me, but there’s no question it’s not everyone’s cup of tea.)

Back at the start of March Mathness I promised the math would be “fun” (really!), but anyone would be forgiven for thinking the previous two posts about Special Relativity weren’t all that much “fun.” (I really enjoy stuff like that, so it’s fun for me, but there’s no question it’s not everyone’s cup of tea.)

Trying to reach for something a bit lighter and potentially more appealing as the promised “fun,” I present, for your dining and dancing pleasure, a trio of number games that anyone can play and which might just tug at the corners of your enjoyment.

We can start with 277777788888899 (and why it’s special).

Continue reading

4 Comments | tags: 277777788888899, algorithm, calculation, Collatz conjecture, computation, Mandelbrot, mathematics, multiplicative persistence, Numberphile | posted in Math

Over the last few weeks I’ve written a series of posts leading up to the idea of human consciousness in a machine. In particular, I focused on the difference between a physical model and a software model, and especially on the requirements of the software model.

Over the last few weeks I’ve written a series of posts leading up to the idea of human consciousness in a machine. In particular, I focused on the difference between a physical model and a software model, and especially on the requirements of the software model.

The series is over, I have nothing particularly new to add, but I’d like to try to summarize my points and provide an index to the posts in this series. It seems I may have given readers a bit of information overload — too much information to process.

Hopefully I can achieve better clarity and brevity here!

Continue reading

30 Comments | tags: AI, algorithm, brain, brain mind problem, chaos theory, computationalism, computer model, computer program, consciousness, human brain, human consciousness, human mind, information theory, mind, My brain is full, stored program computer, Theory of Consciousness, Von Neumann architecture | posted in Computers

No, sorry, I don’t mean the Bletchey Bombe machine that cracked the Enigma cipher. I mean his theoretical machine; the one I’ve been referring to repeatedly the past few weeks. (It wasn’t mentioned at the time, but it’s the secret star of the Halt! (or not) post.)

No, sorry, I don’t mean the Bletchey Bombe machine that cracked the Enigma cipher. I mean his theoretical machine; the one I’ve been referring to repeatedly the past few weeks. (It wasn’t mentioned at the time, but it’s the secret star of the Halt! (or not) post.)

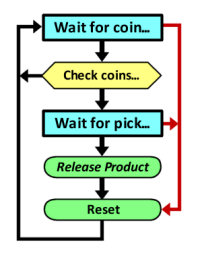

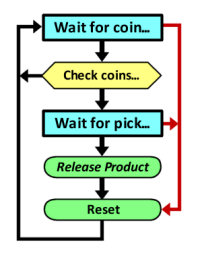

The Turing Machine (TM) is one of our fundamental definitions of calculation. The Church-Turing thesis says that all algorithms have a TM that implements them. On this view, any two actual programs implementing the same algorithm do the same thing.

Essentially, a Turing Machine is an algorithm!

Continue reading

13 Comments | tags: Alan Turing, algorithm, Church-Turing thesis, flowchart, state diagram, Turing Halting Problem, Turing Machine, Universal Turing Machine | posted in Computers

Last time we considered the possibility that human consciousness somehow supervenes on the physical brain, that it only emerges under specific physical conditions. Perhaps, like laser light and microwaves, it requires the right equipment.

Last time we considered the possibility that human consciousness somehow supervenes on the physical brain, that it only emerges under specific physical conditions. Perhaps, like laser light and microwaves, it requires the right equipment.

We also touched on how Church-Turing implies that, if human consciousness can be implemented with software, then the mind is necessarily an algorithm — an abstract mathematical object. But the human mind is presumed to be a natural physical object (or at least to emerge from one).

This time we’ll consider the effect of transcendence on all this.

Continue reading

58 Comments | tags: AI, algorithm, brain mind problem, computationalism, computer model, computer program, consciousness, human brain, human consciousness, human mind, mind, software model, Theory of Consciousness, transcendental numbers, Yin and Yang | posted in Computers

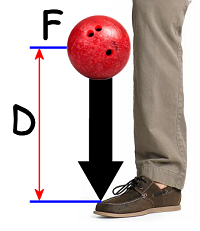

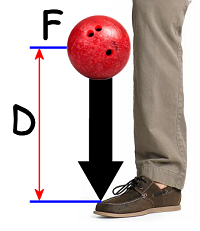

“Ouch!”

Over the past few weeks we’ve explored background topics regarding calculation, code, and computers. That led to an exploration of software models — in particular a software model of the human brain.

The underlying question all along is whether a software model of a brain — in contrast to a physical model — can be conscious. A related, but separate, question is whether some algorithm (aka Turing Machine) functionally reproduces human consciousness without regard to the brain’s physical structure.

Now we focus on why a software model isn’t what it models!

Continue reading

41 Comments | tags: AI, algorithm, bowling ball, brain mind problem, Church-Turing thesis, computationalism, computer model, computer program, consciousness, hot resistor, human brain, human consciousness, human mind, laser light, magnetron, microwaves, mind, software model, Theory of Consciousness | posted in Computers

Last time I introduced four levels of possibility regarding how mind is related to brain. Behind Door #1 is a Holy Grail of AI research, a fully algorithmic implementation of a human mind. Behind Door #4 is an ineffable metaphysical mind no machine can duplicate.

Last time I introduced four levels of possibility regarding how mind is related to brain. Behind Door #1 is a Holy Grail of AI research, a fully algorithmic implementation of a human mind. Behind Door #4 is an ineffable metaphysical mind no machine can duplicate.

The two doors between lead to physical models that recapitulate the structure of the human brain. Behind Door #3 is the biology of the brain, a model we know creates mind. Behind Door #2 is the network of the brain, which we presume encodes the mind regardless of its physical construction.

This time we’ll look more closely at some distinguishing details.

Continue reading

14 Comments | tags: AI, algorithm, brain, calculator, computationalism, computer model, computer program, consciousness, enchanted loom, human brain, human consciousness, LTP, neural correlates, qualia, self-awareness, slide rule, software model, synapse | posted in Computers

Last week we took a look at a simple computer software model of a human brain. (We discovered that it was big, requiring dozens of petabytes!) One goal of such models is replicating consciousness — a human mind. That can involve creating a (potentially superior) new mind or uploading an existing human mind (a very different goal).

Last week we took a look at a simple computer software model of a human brain. (We discovered that it was big, requiring dozens of petabytes!) One goal of such models is replicating consciousness — a human mind. That can involve creating a (potentially superior) new mind or uploading an existing human mind (a very different goal).

Now that we’ve explored the basics of calculation, code (software), computers, and (computer software) models, we’re ready to explore what’s involved in attempting to model a (human) mind.

I’m dividing the possibilities into four basic levels.

Continue reading

18 Comments | tags: AI, algorithm, brain, computationalism, computer model, computer program, consciousness, enchanted loom, human brain, human consciousness, human mind, Isaac Asimov, mind, physicalism, positronic brain, qualia, René Descartes | posted in Computers

The ultimate goal is a consideration of how to create a working model of the human mind using a computer. Since no one knows how to do that yet (or if it’s even possible to do), there’s a lot of guesswork involved, and our best result can only be a very rough estimate. Perhaps all we can really do is figure out some minimal requirements.

The ultimate goal is a consideration of how to create a working model of the human mind using a computer. Since no one knows how to do that yet (or if it’s even possible to do), there’s a lot of guesswork involved, and our best result can only be a very rough estimate. Perhaps all we can really do is figure out some minimal requirements.

Given the difficulty we’ll start with some simpler software models. In particular, we’ll look at (perhaps seeming oddity of) using a computer to model a computer (possibly even itself).

The goal today is to understand what a software model is and does.

Continue reading

4 Comments | tags: algorithm, American checkers, checkers, complexity, computer model, computer program, English draughts, Kolmogorov complexity, software, software model, state space | posted in Computers

Imagine the watershed for a river. Every drop of water that falls in that area, if it doesn’t evaporate or sink into the ground, eventually makes its way, through creeks, streams, and rivers, to the lake or ocean that is the shed’s final destination. The visual image is somewhat like the veins in a leaf. Or the branches of the leaf’s tree.

Imagine the watershed for a river. Every drop of water that falls in that area, if it doesn’t evaporate or sink into the ground, eventually makes its way, through creeks, streams, and rivers, to the lake or ocean that is the shed’s final destination. The visual image is somewhat like the veins in a leaf. Or the branches of the leaf’s tree.

Back at the start of

Back at the start of  Over the last few weeks I’ve written a series of posts leading up to the idea of human consciousness in a machine. In particular, I focused on the difference between a physical model and a software model, and especially on the requirements of the software model.

Over the last few weeks I’ve written a series of posts leading up to the idea of human consciousness in a machine. In particular, I focused on the difference between a physical model and a software model, and especially on the requirements of the software model. No, sorry, I don’t mean the

No, sorry, I don’t mean the

The ultimate goal is a consideration of how to create a working model of the human mind using a computer. Since no one knows how to do that yet (or if it’s even possible to do), there’s a lot of guesswork involved, and our best result can only be a very rough estimate. Perhaps all we can really do is figure out some minimal requirements.

The ultimate goal is a consideration of how to create a working model of the human mind using a computer. Since no one knows how to do that yet (or if it’s even possible to do), there’s a lot of guesswork involved, and our best result can only be a very rough estimate. Perhaps all we can really do is figure out some minimal requirements.