Robot Apocalypse!

Recently, fellow WordPress blogger Anonymole mentioned in a comment here that he enjoyed Day Zero, a 2021 science fiction novel by C. Robert Cargill. I checked out the Wikipedia article about it, and thought it sounded interesting. Turned out my library had it, so I checked it out (in both senses of the word).

Recently, fellow WordPress blogger Anonymole mentioned in a comment here that he enjoyed Day Zero, a 2021 science fiction novel by C. Robert Cargill. I checked out the Wikipedia article about it, and thought it sounded interesting. Turned out my library had it, so I checked it out (in both senses of the word).

And I agree! It’s very good, and I’d recommend it for any science fiction fan, especially fans of hard SF. It’s the story of a robot uprising that kills most of the humans but as told from the first-person point of view of one of the robots.

It’s the story of his desperate attempt to save the child he was bought to nourish and protect as the world crumbles around them.

Catherine Aird & Lawrence Block

It has been just over six months since my last Mystery Monday post. It’s not that I haven’t been reading mystery novels (my second-favorite genre) but that I just haven’t been moved to write a post (a bit of a general problem the last year or so).

It has been just over six months since my last Mystery Monday post. It’s not that I haven’t been reading mystery novels (my second-favorite genre) but that I just haven’t been moved to write a post (a bit of a general problem the last year or so).

But I haven’t been idle, quite to the contrary. I’ve now gone through the other three (of the five) character series by Lawrence Block (Keller the Killer, Chip Harrison, and Evan Tanner). Prolific writer, Block.

And I’ve read nearly all of the Sloan and Crosby murder mysteries (also known as the Chronicles of Calleshire) by yet another British writer, Catherine Aird.

Margery Allingham & Ellery Queen

If you search for [queens of crime] you’ll turn up four names: Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Ngaio Marsh, and Margery Allingham. They’re all leading lights from the Golden Age of Detective Fiction.

If you search for [queens of crime] you’ll turn up four names: Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Ngaio Marsh, and Margery Allingham. They’re all leading lights from the Golden Age of Detective Fiction.

I’ve known about and read Christie and Sayers since grade and high school, respectively. I’d seen Ngaio Marsh’s name many times over the years but don’t recall ever seeing Allingham’s. Recently I’ve worked through Marsh’s oeuvre. Now I’m exploring Allingham’s.

I’m also working through another queen: Ellery Queen.

Ngaio Marsh

Back in February, I posted about how I was starting to explore murder mystery author P.D. James (1920-2014). As it turned out, I came to decide she wasn’t really my cup of tea. I’ll say a bit more about that later in this Mystery Monday post, but the main topic today is Ngaio Marsh (1895-1982), a murder mystery author from New Zealand who definitely is my cup of tea.

Back in February, I posted about how I was starting to explore murder mystery author P.D. James (1920-2014). As it turned out, I came to decide she wasn’t really my cup of tea. I’ll say a bit more about that later in this Mystery Monday post, but the main topic today is Ngaio Marsh (1895-1982), a murder mystery author from New Zealand who definitely is my cup of tea.

She’s a close contemporary of Agatha Christie (1890-1976), born just five years later and dying just six years after Christie did. She lived 86 years compared to Christie’s 85.

More relevant to me, she’s a close contemporary in terms of her murder mysteries. I’ve read 15 of her novels so far and have thoroughly enjoyed each one.

Rucker: Juicy Ghosts

For today’s Sci-Fi Saturday, we have Juicy Ghosts (2021), the latest novel from mathematician turned science fiction writer Rudy Rucker. The library blurb describes it as “a fast-paced adventure novel, with startling science, engaging dialog — and a happy ending. […] It’s also a redemptive political tale, reacting to the chaos of a contested US presidential election.”

For today’s Sci-Fi Saturday, we have Juicy Ghosts (2021), the latest novel from mathematician turned science fiction writer Rudy Rucker. The library blurb describes it as “a fast-paced adventure novel, with startling science, engaging dialog — and a happy ending. […] It’s also a redemptive political tale, reacting to the chaos of a contested US presidential election.”

It’s very clear from the text — and explicit in his Afterward — that the novel was inspired by recent American politics. The story features a cruel tyrannical President who, backed by Big Money, steals a third term.

And is taken down by technological wizards. As the blurb said, a happy ending.

P.D. James

Yesterday I at long last dipped my toe into yet another author I’ve been meaning to explore for (quite literally) many decades: P.D. James (1920-2014). My dad — from whom I inherited my love of mysteries — thought she was pretty good, so she’s been on my list for a long time.

Yesterday I at long last dipped my toe into yet another author I’ve been meaning to explore for (quite literally) many decades: P.D. James (1920-2014). My dad — from whom I inherited my love of mysteries — thought she was pretty good, so she’s been on my list for a long time.

While not nearly as prolific as the great Dame Agatha Christie, James very much follows in, and even extends, the tradition of British murder mysteries.

So far, I’ve only read a bunch of her short stories and gotten started on one of her novels — which I’ll be returning to and curling up with as soon as I finish this (hopefully short) post.

Asimov, Gibson, Gaiman…

The Sci-Fi Saturday posts lately have reported on books by Robert J. Sawyer, my new favorite science fiction author, or on books by Ben Bova, one of the notable stars in the SF firmament. A couple of posts recommended interesting movies (this one and that one).

The Sci-Fi Saturday posts lately have reported on books by Robert J. Sawyer, my new favorite science fiction author, or on books by Ben Bova, one of the notable stars in the SF firmament. A couple of posts recommended interesting movies (this one and that one).

This month I’ve been exploring other things. For instance, other parts of YouTube than I usually frequent (see yesterday’s post). Relevant here, other science fiction authors. (And maybe a TV show if there’s space.)

Today’s post reports on books by: Isaac Asimov, William Gibson, Neil Gaiman, and James S. A. Corey.

Sawyer: WWW

What if, as more than one science fiction story has imagined, the sheer size and complexity of the World Wide Web made it become self-aware. And, what if, contrary to most of those stories, it was wonderful in every sense of the word. What if it meant world peace, freedom, and humanity at long last growing up.

What if, as more than one science fiction story has imagined, the sheer size and complexity of the World Wide Web made it become self-aware. And, what if, contrary to most of those stories, it was wonderful in every sense of the word. What if it meant world peace, freedom, and humanity at long last growing up.

That’s the vision Robert J. Sawyer presents in his WWW trilogy, which consists of Wake (2009), Watch (2010), and Wonder (2011). It’s the tale of a young woman blind from birth who gains sight, a bonobo-chimpanzee hybrid who makes a choice, and an emergent machine-based superintelligence who wants to serve man.

And not, he adds, in the cookbook sense.

Robert J. Sawyer

Quite some years ago, poking around Apple’s collection of science fiction eBooks, I noticed Calculating God (2000), by Robert J. Sawyer. I’d never heard of him but got the impression he was a literary author who’d written a science fiction novel about God.

Quite some years ago, poking around Apple’s collection of science fiction eBooks, I noticed Calculating God (2000), by Robert J. Sawyer. I’d never heard of him but got the impression he was a literary author who’d written a science fiction novel about God.

But the book’s description intrigued enough to add to my wish list. It sat there for years. An unknown author, a very long reading list, and Apple’s obnoxious prices, all conspired to keep me from buying it. Recently I noticed Apple had removed it from their catalog.

The library didn’t have it either, but an author search turned up lots of his other SF novels. I tried one, loved it, then tried three more with good result. We seem to have similar interests and sensibilities.

Stephenson: The Big U

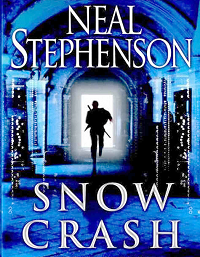

Last post I mentioned that I’d started reading The Big U (1984), by Neal Stephenson, one of my favorite authors. (See these posts.) Other than a few books done with co-authors, I’ve read nearly everything of his. The exceptions are The Baroque Cycle trilogy (which I’ve been putting off) and, until now, The Big U, his very first novel.

Last post I mentioned that I’d started reading The Big U (1984), by Neal Stephenson, one of my favorite authors. (See these posts.) Other than a few books done with co-authors, I’ve read nearly everything of his. The exceptions are The Baroque Cycle trilogy (which I’ve been putting off) and, until now, The Big U, his very first novel.

Stephenson didn’t become popular until his third novel, Snow Crash (1992), which is still one of my favorites (perhaps, in part, because it was the first of his novels that I read). As with his second novel, Zodiac (1988), his first is a biting present-day social satire and not really science fiction.

That said, it does involve nuclear waste, giant mutant rats, and a student-made rail gun.

Smolin: Einstein’s Unfinished Revolution

Earlier this month I posted about Quantum Reality (2020), Jim Baggott’s recent book about quantum realism. Now I’ve finished another book with a very similar focus, Einstein’s Unfinished Revolution: The Search for What Lies Beyond the Quantum (2019), by Lee Smolin.

Earlier this month I posted about Quantum Reality (2020), Jim Baggott’s recent book about quantum realism. Now I’ve finished another book with a very similar focus, Einstein’s Unfinished Revolution: The Search for What Lies Beyond the Quantum (2019), by Lee Smolin.

One difference between the books is that Smolin is a working theorist, so he offers his own realist theory. As with his theory of cosmic selection via black holes (see his 1997 book, The Life of the Cosmos), I’m not terribly persuaded by his theory of “nads” (named after Leibniz’s monads). I do appreciate that Smolin himself sees the theory as a bit of a wild guess.

There were also some apparent errors that raised my eyebrows.

Reynolds, Bova (redux)

Two weeks ago, for Sci-Fi Saturday I posted about Absolution Gap (2003), by Alastair Reynolds. It’s the third book in his Revelation Space series. If you read the post, you know I didn’t care for it. Really didn’t care for it, especially after some disappointment with his writing style in the second book in the series, Redemption Ark (2002).

Two weeks ago, for Sci-Fi Saturday I posted about Absolution Gap (2003), by Alastair Reynolds. It’s the third book in his Revelation Space series. If you read the post, you know I didn’t care for it. Really didn’t care for it, especially after some disappointment with his writing style in the second book in the series, Redemption Ark (2002).

Now I’ve read Inhibitor Phase (2021), the last book of the series. For the first three-quarters of the book, I was once again rather enjoying Alastair Reynolds. Unfortunately, the last quarter, not to mention the resolution to the series, was a huge disappointment.

In that previous post I also mentioned Uranus (2020), by Ben Bova. Now I’ve read the sequel, Neptune (2021), and it was… strange.

Baggott: Quantum Reality

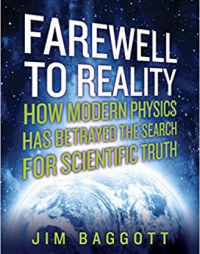

I recently read, and very much enjoyed, Quantum Reality (2020) by Jim Baggot, an author (and speaker) I’ve come to like a lot. I respect his grounded approach to physics, and we share that we’re both committed to metaphysical realism. Almost two years ago, I posted about his 2014 book Farewell to Reality: How Modern Physics Has Betrayed the Search for Scientific Truth, which I also very much enjoyed.

I recently read, and very much enjoyed, Quantum Reality (2020) by Jim Baggot, an author (and speaker) I’ve come to like a lot. I respect his grounded approach to physics, and we share that we’re both committed to metaphysical realism. Almost two years ago, I posted about his 2014 book Farewell to Reality: How Modern Physics Has Betrayed the Search for Scientific Truth, which I also very much enjoyed.

This book is one of a whole handful of related books I bought recently now that I’m biting one more bullet and buying Kindle books from Amazon (the price being a huge draw; science books tend to be pricy in physical form).

The thread that runs through them is that each author is committed to realism, and each is disturbed about where modern physics has gone. Me, too!

Bova, Stephenson, Reynolds

Because they are intended for mass consumption, there are few modern science fiction movies or TV shows that really hit the mark for me. Sturgeon’s famous statement about everything being 90% crap seems even more true with mass media. It’s no less true of science fiction books, but there are so many more of those that it’s easier to find good ones. The trick is finding good authors.

Because they are intended for mass consumption, there are few modern science fiction movies or TV shows that really hit the mark for me. Sturgeon’s famous statement about everything being 90% crap seems even more true with mass media. It’s no less true of science fiction books, but there are so many more of those that it’s easier to find good ones. The trick is finding good authors.

Neal Stephenson is one author that usually delivers for me. Ben Bova is another good one, although until recently it was decades since I read his work. Alastair Reynolds, compared to them, is a new entry on the scene. All three write hard SF — my favored flavor of science fiction.

Unfortunately, the last Reynolds books I read was a disappointment.

Egan: Zendegi

Greg Egan is among my favorite science fiction authors. He especially stands out to me if I limit the field to authors currently writing. Egan might not be a working scientist, but he has a degree in mathematics and his work is known in that field. His math and physics background shine brightly in his science fiction writing and that light is why I like his stories so much. I love hard SF most, and Egan delivers the goods.

Greg Egan is among my favorite science fiction authors. He especially stands out to me if I limit the field to authors currently writing. Egan might not be a working scientist, but he has a degree in mathematics and his work is known in that field. His math and physics background shine brightly in his science fiction writing and that light is why I like his stories so much. I love hard SF most, and Egan delivers the goods.

I just finished his 2010 novel, Zendegi. There have been some recent disappointments from my reading list (including the last Egan story I read), so it’s nice to read a book that I thoroughly enjoyed and find worth posting about.

Zendegi is about what it means to be human…

“King”: FKA USA

Yesterday I finished FKA USA (2019), by “Reed King” — a pseudonym of a “New York Times bestselling author and TV writer.” It was a new book at my library, and the blurb about it concluded, “FKA USA is the epic novel we’ve all be waiting for about the American end of times, […] It is a masterwork of ambition, humor, and satire with the power to make us cry, despair, and laugh out loud all at once. It is a tour de force unlike anything else you will read this year.”

Yesterday I finished FKA USA (2019), by “Reed King” — a pseudonym of a “New York Times bestselling author and TV writer.” It was a new book at my library, and the blurb about it concluded, “FKA USA is the epic novel we’ve all be waiting for about the American end of times, […] It is a masterwork of ambition, humor, and satire with the power to make us cry, despair, and laugh out loud all at once. It is a tour de force unlike anything else you will read this year.”

Sounded good. It had a long wait list, so I put it on hold back in mid-October. It became available in mid-December. It weighs in at over 1000 e-pages, so it’s taken me a few days to finish. The length is one reason though. I didn’t find the book to be much of a page-turner, and I’m afraid I skimmed bits of the last chapters.

Victoria wasn’t amused; I wasn’t engaged. Or amused.

VanderMeer: Annihilation

I originally planned this Sci-Fi Saturday post as a positive review of the Southern Reach trilogy by Jeff VanderMeer, but Burns really nailed it about plans “gang aft agley.” I’ll tell you right now I bailed about halfway through the second book because I wasn’t enjoying the read, was utterly bored by the story, and had found VanderMeer’s writing style annoying from the beginning.

I originally planned this Sci-Fi Saturday post as a positive review of the Southern Reach trilogy by Jeff VanderMeer, but Burns really nailed it about plans “gang aft agley.” I’ll tell you right now I bailed about halfway through the second book because I wasn’t enjoying the read, was utterly bored by the story, and had found VanderMeer’s writing style annoying from the beginning.

So this isn’t a positive review, but I’m willing to credit much of the lack of connection on my taste, both with regard to content and to writing style. The author and the trilogy are held in high regard, and I don’t at all dispute the quality of the storytelling. It’s just not for me.

His Wiki page says he’s compared to Borges and Kafka (which seems apt), and I’ve never cared that much for their writing, either.

Zer0s and Burning Roses

I’ve been a voracious reader all my life, and as much as my college career pointed towards one in movies or TV, I’ve always ranked books as vastly superior. Put it this way: Although I once presumed (and still do) to be worthy of making TV shows or movies, I’ve never felt skilled enough — or driven enough — to write fiction.

I’ve been a voracious reader all my life, and as much as my college career pointed towards one in movies or TV, I’ve always ranked books as vastly superior. Put it this way: Although I once presumed (and still do) to be worthy of making TV shows or movies, I’ve never felt skilled enough — or driven enough — to write fiction.

Which no doubt contributes to my admiration and appreciation of those who can pull me into their fictional world and entertain, educate, or enlighten me with only their words (no score, no images, no editing).

Last week I read Zer0s (2015), by Chuck Wendig, and Burning Roses (2020), by S.L. Huang, and thoroughly enjoyed both. In fact, I gulped down both of these fast-paced (and very different) adventures in single sittings. Both would make pretty good movies, too.

Ellis: The Truth of the Divine

Last year I read and very much enjoyed Axiom’s End (2020), a debut novel by film critic and YouTuber Lindsay Ellis. It’s the first book of her Noumena series, which is about powerful aliens showing up on an unsuspecting Earth. It made the New York Times Best Seller list and generated a fair amount of favorable attention.

Last year I read and very much enjoyed Axiom’s End (2020), a debut novel by film critic and YouTuber Lindsay Ellis. It’s the first book of her Noumena series, which is about powerful aliens showing up on an unsuspecting Earth. It made the New York Times Best Seller list and generated a fair amount of favorable attention.

Earlier this year I preordered the second book, The Truth of the Divine (2021), and it finally dropped last month. I had high hopes and much anticipation about where Ellis would take her story. Sadly, I found myself sorely disappointed by this second installment. This isn’t a positive review.

For balance I’ll mention two books I did enjoy, Neuromancer (1984), by William Gibson, and a new comedy by David Brin.

Egan: Orthogonal Series

Generally I like my SF hard, even diamond hard. I don’t disdain fantasy; some of my favorite stories are fantastic. (As I’ve said often, Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series is my #1, my proverbial desert island companion.) But I definitely lean towards harder SF.

Generally I like my SF hard, even diamond hard. I don’t disdain fantasy; some of my favorite stories are fantastic. (As I’ve said often, Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series is my #1, my proverbial desert island companion.) But I definitely lean towards harder SF.

Growing up it was, of course, the Holy Trinity, Asimov, Clarke, Heinlein, but there was also Clement, Niven, and many others who stirred a large measure of science into their fiction. More recently the list of hard SF authors includes Forward, Steele, Stephenson, and a particular favorite of mine, Greg Egan.

I can safely say his Orthogonal series is as hard as science fiction gets.

Butler: Kindred

Not long ago I posted All the Christie as a follow-up to an earlier post about Agatha Christie. I’d read her when I was younger but only realized what an extraordinary writer (and person) she was when I revisited her work recently.

Not long ago I posted All the Christie as a follow-up to an earlier post about Agatha Christie. I’d read her when I was younger but only realized what an extraordinary writer (and person) she was when I revisited her work recently.

In contrast, I knew Octavia E. Butler only by reputation and some short stories I’d read. This past August I finally set out to correct this egregious oversight for a serious science fiction fan. As it turned out, I sat down to a delicious feast by another extraordinary cook. I relished every crumb, from appetizer to dessert. (I even shamelessly licked the plate.)

The dessert was her finest (and most popular) dish, Kindred (1979).

Butler: Parable Series

This past August I posted about Octavia E. Butler, a highly regarded science fiction author I finally got around to exploring. Now that I’ve read all her work (but for one novel), I’ve gone from being very impressed to being slightly in awe. Her reputation is very well deserved.

This past August I posted about Octavia E. Butler, a highly regarded science fiction author I finally got around to exploring. Now that I’ve read all her work (but for one novel), I’ve gone from being very impressed to being slightly in awe. Her reputation is very well deserved.

Recently I finished her two-book Parable series, Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998). It’s the story of a woman’s lifelong journey building what she names Earthseed, a modern religion with a concrete goal.

What blew my mind, though, was how eerily prescient her President Jarret was of our POTUS45. Nailed it — including the infamous slogan.

Wilczek: Fundamentals

I just finished Fundamentals: Ten Keys to Reality (2021), by Frank Wilczek. It’s yet another book explaining fundamental physics for lay readers, and it does so pretty much entirely within the bounds of mainstream science. I enjoyed reading it, but it’s mainly a review of physics as we know it.

I just finished Fundamentals: Ten Keys to Reality (2021), by Frank Wilczek. It’s yet another book explaining fundamental physics for lay readers, and it does so pretty much entirely within the bounds of mainstream science. I enjoyed reading it, but it’s mainly a review of physics as we know it.

I saw it on the library’s list of new books and put it on hold back on May 14th. It didn’t become available until September 3 — more than a three-month wait. Apparently lots of people wanted to read it.

Bottom line, I recommend it as an easy and enjoyable read, especially for those with a more casual interest in physics.

Monday the Blogger Posted

The last few months I’ve been dipping into the Rabbi Small murder mysteries, which are written by author and professor of English Harry Kemelman (1908–1996). The series is in the Amateur Sleuth sub-genre. In this case the amateur who is constantly solving murders is a Jewish rabbi.

The last few months I’ve been dipping into the Rabbi Small murder mysteries, which are written by author and professor of English Harry Kemelman (1908–1996). The series is in the Amateur Sleuth sub-genre. In this case the amateur who is constantly solving murders is a Jewish rabbi.

The Tony Hillerman books (Leaphorn and Chee) are filled with Navajo background. The Jonathan Gash books (Lovejoy) are filled with antiques background. The Lawrence Block books (Bernie the burglar) are filled with burglary background. In all cases, this background enriches the reading and can be educational (the Hillerman books especially).

Harry Kemelman’s books are enriched by all the Jewish background.

Smolin: Time Reborn

I’ve been reading science texts almost as long as I’ve been reading anything. Over those years, many scientists and science writers have taught me much of what I know about science. (Except for a Computer Science minor, and general science classes, most of my formal education was in the Liberal Arts.)

I’ve been reading science texts almost as long as I’ve been reading anything. Over those years, many scientists and science writers have taught me much of what I know about science. (Except for a Computer Science minor, and general science classes, most of my formal education was in the Liberal Arts.)

Recently I read Time Reborn (2013), by Lee Smolin, a theoretical physicist whose personality and books I’ve enjoyed. I don’t always agree with his ideas, but I’ve found I do tend to agree with his approaches to, and overall sense of, physics.

However in this case I almost feel Smolin, after long and due consideration, has come around to my way of thinking!

Octavia E. Butler

Retirement, along with online access to the library, has opened the door to exploring authors I’ve meant to read for ages. For example, I’d always meant to read one of my dad’s favorite books, The Name of the Rose (1980) by Umberto Eco, but it wasn’t until last year that I finally did (and it was really good; I can see why he loved it).

Retirement, along with online access to the library, has opened the door to exploring authors I’ve meant to read for ages. For example, I’d always meant to read one of my dad’s favorite books, The Name of the Rose (1980) by Umberto Eco, but it wasn’t until last year that I finally did (and it was really good; I can see why he loved it).

As a fan of literary science fiction for over six decades, I’ve long felt pressure to explore the works of Octavia Butler (1947–2006). Over the years, in collections, I’ve read some of her short stories (and found them tasty). It was only in the last month or so that I finally got into her novels.

And, my, oh my! She is every bit as good as everyone says she is.

Like Being a Dog

Back in 1974 Thomas Nagel published the now-famous paper What is it like to be a bat? It was an examination of the mind-body problem. Part of Nagel’s argument includes the notion that we can never really know what it’s like to be a bat. As W.G. Sebald said, “Men and animals regard each other across a gulf of mutual incomprehension.”

Back in 1974 Thomas Nagel published the now-famous paper What is it like to be a bat? It was an examination of the mind-body problem. Part of Nagel’s argument includes the notion that we can never really know what it’s like to be a bat. As W.G. Sebald said, “Men and animals regard each other across a gulf of mutual incomprehension.”

But in What It’s Like to Be a Dog: And Other Adventures in Animal Neuroscience (2017) neuroscientist Gregory Berns disagrees. In his opinion Nagel got it wrong. The Sebald Gap closes from both ends. Firstly because animal minds aren’t really that different from ours. Secondly because we can extrapolate our experiences to those of dogs, dolphins, or bats.

I think he has a point, but I also think he’s misreading Nagel a little.

All the Christie

Okay, not all the Agatha Christie — not yet — but I’m getting close. I’ve read all the Hercule Poirot short stories and novels (save one; the last). I’ve read all the Miss Marple novels and all the Tommy and Tuppence novels (but none of the short stories in either case). I’ve read a few of the stand alone novels, but there are a number of those to go. (I’ve even read a collection of her plays.)

Okay, not all the Agatha Christie — not yet — but I’m getting close. I’ve read all the Hercule Poirot short stories and novels (save one; the last). I’ve read all the Miss Marple novels and all the Tommy and Tuppence novels (but none of the short stories in either case). I’ve read a few of the stand alone novels, but there are a number of those to go. (I’ve even read a collection of her plays.)

The very last novels are disappointing, but the vast bulk of Christie’s work is a genuine treasure. To be honest, I never realized how engaging and wonderful her writing actually is. I’ve been a Poirot fan since childhood but never explored her other work because I saw it as ‘too old-fashioned and ordinary.’ My mistake!

Speaking of better late than never, recently I’ve finally explored a few other mystery authors, one of which was long overdue…

The Long Baxter

After eight books I think it’s safe to say that I am not, and probably never will be, a fan of science fiction author Stephen Baxter. Just over a year ago I read his Manifold trilogy and was notably underwhelmed (see this post about book one and this post about the whole trilogy).

After eight books I think it’s safe to say that I am not, and probably never will be, a fan of science fiction author Stephen Baxter. Just over a year ago I read his Manifold trilogy and was notably underwhelmed (see this post about book one and this post about the whole trilogy).

Recently I finished The Long Earth, a five-book series Baxter co-authored with my all-time, no-exceptions, favorite fiction author, Terry Pratchett. The series is based on an interesting parallel worlds idea from a short story, The High Meggas, Pratchett wrote back in the mid-1980s.

Much to my disappointment, I was also notably underwhelmed by this series.

Scalzi: The Interdependency

I thoroughly enjoyed the first John Scalzi book I read, Redshirts. I thought it was delightful and definitely my kind of book. I also very much enjoyed the second Scalzi book I read, The Android’s Dream. Because of that, I’ve been looking forward to reading his trilogy, The Interdependency.

I thoroughly enjoyed the first John Scalzi book I read, Redshirts. I thought it was delightful and definitely my kind of book. I also very much enjoyed the second Scalzi book I read, The Android’s Dream. Because of that, I’ve been looking forward to reading his trilogy, The Interdependency.

This past week, courtesy of online library books, I finally did, and I do regret to report that I found the series rather underwhelming. I ended up skimming through the last half of the last book just to find out how it all turned out.

I think the biggest issue for me was lack of action. There was a ton of narration, explanation, internal monologue, and talking, but there wasn’t much action.

2020 Mystery Wrap-up

In light of yesterday’s post, I was initially a bit confused. Is this, because it’s a wrap-up, the last Mystery Monday post of 2020 or, per yesterday, the first one of 2021? I say we wait until after the popping of the champagne corks, so this is the last one of the past year.

In light of yesterday’s post, I was initially a bit confused. Is this, because it’s a wrap-up, the last Mystery Monday post of 2020 or, per yesterday, the first one of 2021? I say we wait until after the popping of the champagne corks, so this is the last one of the past year.

No question that this is a wrap-up of an active reading year when it comes to (murder) mysteries. I’ve enjoyed the genre from a very early age (the enjoyment was handed down by my dad). In this atrocious year, they’ve provided a welcome escape and respite.

The year also marks my return to library lending, albeit electronically.

Ball: Beyond Weird

I just finished reading Beyond Weird: Why Everything You Thought You Knew About Quantum Physics Is Different (2018) by science writer Philip Ball. I like Ball a lot. He seems well grounded in physical reality, and I find his writing style generally transparent, clear, and precise.

I just finished reading Beyond Weird: Why Everything You Thought You Knew About Quantum Physics Is Different (2018) by science writer Philip Ball. I like Ball a lot. He seems well grounded in physical reality, and I find his writing style generally transparent, clear, and precise.

As is often the case with physics books like these, the last chapter or three can get a bit speculative, even a bit vague, as the author looks forward to imagined future discoveries or, groundwork completed, now presents their own view. Which is fine with me so long as it’s well bracketed as speculation. I give Ball high marks all around.

The theme of the book is what Ball means by “beyond weird.”

Brave New World

In every literary genre (in every type of art, really), there are classics that stand out and often participate in forming the language, or at least some of the territory, of the genre. That is part of what makes these works classics. (Lord of the Rings is an ultimate classic — all Medieval fantasy since is in reference to it.)

In every literary genre (in every type of art, really), there are classics that stand out and often participate in forming the language, or at least some of the territory, of the genre. That is part of what makes these works classics. (Lord of the Rings is an ultimate classic — all Medieval fantasy since is in reference to it.)

I suspect all serious readers have a classic or two they’ve never gotten around to. Last week I finally got around to reading the classic science fiction novel, Brave New World (1932), by Aldous Huxley.

For a novel written 88 years ago, it’s surprisingly prescient and relevant.

Gleick: The Information

I just finished The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood (2011), by historian author James Gleick. This past summer I read his book, Time Travel (2016), which was about time travel in fiction and in our hearts. [see Passing Time (My bad; it should have been titled Gleick: Time Travel, but I can never resist a pun.)]

I just finished The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood (2011), by historian author James Gleick. This past summer I read his book, Time Travel (2016), which was about time travel in fiction and in our hearts. [see Passing Time (My bad; it should have been titled Gleick: Time Travel, but I can never resist a pun.)]

If you read my post about the time travel book, you know I didn’t care for it, although I place the blame on my expectations, not the book. I do find Gleick, as I said then, “ambling, rambling, and meandering,” but I’m sure many greatly enjoy his excursions. I ended that review mentioning I’d like to read another book of his (a trend takes two data points).

The Information is that book, and I did like it more than Time Travel.

Math Books

There are many science-minded authors and working physicists who write popular science books. While there aren’t as many math-minded authors or working mathematicians writing popular math books, it’s not a null set. I’ve explored two such authors recently: mathematician Steven Strogatz and author David Berlinski.

There are many science-minded authors and working physicists who write popular science books. While there aren’t as many math-minded authors or working mathematicians writing popular math books, it’s not a null set. I’ve explored two such authors recently: mathematician Steven Strogatz and author David Berlinski.

Strogatz wrote The Joy of X (2012), which was based on his New York Times columns popularizing mathematics. I would call that a must-read for anyone with a general interest in mathematics. I just finished his most recent, Infinite Powers (2019), and liked it even more.

Berlinski, on the other hand, I wouldn’t grant space on my bookshelf.

Tess Gerritsen

One of the ways I’ve coped during this insanest of years is by escaping into fiction, and it’s hard to beat the sheer escapism of a good murder mystery. Science fiction, my other favorite escapist drug, particularly the good stuff, is often parable, prophecy, or pointed social examination, but a murder mystery is typically just a rippin’ good yarn.

One of the ways I’ve coped during this insanest of years is by escaping into fiction, and it’s hard to beat the sheer escapism of a good murder mystery. Science fiction, my other favorite escapist drug, particularly the good stuff, is often parable, prophecy, or pointed social examination, but a murder mystery is typically just a rippin’ good yarn.

The older classics especially, for instance Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot and Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe (two favorites of mine), when you come down to it, are utterly preposterous. Fairy tales staring a fussy Belgian with his mustaches or a corpulent epicurean who never leaves his house, both brilliant and eccentric, both prone to that final scene, everyone gathered, for the denouement, “J’accuse!”

Tess Gerritsen’s Rizzoli & Isles series is a very different kind of yarn.

Chambers: Small Angry Planet

Last week I read a science fiction novel I’d seen in a number of “must read” lists: The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet (2014), by Becky Chambers. The title certainly appealed to me, and, along with the book’s cover, it seemed like it might be fun, funny, or even zany.

Last week I read a science fiction novel I’d seen in a number of “must read” lists: The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet (2014), by Becky Chambers. The title certainly appealed to me, and, along with the book’s cover, it seemed like it might be fun, funny, or even zany.

I like to let things unfold, so I usually avoid trailers and reviews until after I’ve seen or read for myself. A few months ago I wrote about Axiom’s End, which I really liked. I was anticipating a similar ‘great new author’ experience. (I’ve also mentioned the S.L. Huang Cas Russell books. I kinda liked those, too, so I’m definitely feeling favorable towards new authors.)

Unfortunately, I didn’t like this book at all.

Old School Viral

Remember when “going viral” didn’t mean hospitalization and possible death? (Obviously if we go back even further to the original meaning, it did.) I had an old post go briefly and mildly viral last week. Big traffic spike with a very rapid tail-off. Most bemusing.

Remember when “going viral” didn’t mean hospitalization and possible death? (Obviously if we go back even further to the original meaning, it did.) I had an old post go briefly and mildly viral last week. Big traffic spike with a very rapid tail-off. Most bemusing.

I’ll tell you about that, and about a spike on another post, this one weirdly seasonal — huge spike ever September for three years now. I have no idea what’s going on there. Most puzzling.

There is also a book about the friendship and conflict between Albert Einstein and Erwin Schrödinger that I thoroughly enjoyed despite it not being my typical sort of reading (I’ve never gone in much for either history or biography).

Agatha Christie

Shakespeare talked about the ages of man, and it’s well known that age seems to revert us to our youth. The last handful of years that’s been true for me with regard to mystery authors. For the first time in many decades I’m reading (or rather re-reading) Dorothy L. Sayers (Lord Peter Wimsey), Rex Stout (Nero Wolfe), and others from my past.

Shakespeare talked about the ages of man, and it’s well known that age seems to revert us to our youth. The last handful of years that’s been true for me with regard to mystery authors. For the first time in many decades I’m reading (or rather re-reading) Dorothy L. Sayers (Lord Peter Wimsey), Rex Stout (Nero Wolfe), and others from my past.

This month I’ve been enjoying Agatha Christie and her Hercule Poirot novels. I got into them after finishing a collection of 51 short stories starring her famous Belgian detective (with his “egg-shaped head” and giant mustaches). Reading those put me in the mood to revisit the novels.

And I must say I’ve been thoroughly enjoying them!

Sci-Fi September

The post’s title is something of a misnomer (as there has been little, if any, science fiction for me this month), but I have an absolute and abiding affection for alliteration. (Which explains Sci-Fi Saturday, Mystery Monday, TV Tuesday, and Wednesday Wow.) I couldn’t resist the title once it popped into my mind.

The post’s title is something of a misnomer (as there has been little, if any, science fiction for me this month), but I have an absolute and abiding affection for alliteration. (Which explains Sci-Fi Saturday, Mystery Monday, TV Tuesday, and Wednesday Wow.) I couldn’t resist the title once it popped into my mind.

Seriously, about the only SF in September was opening and shelving a box of books. But since October will be so political, I want to clear some notes. Call it a Fall Clearance — Low, Low Prices! — Everything Must Go!

Some rake their lawn of fallen leaves. For me, it’s that pile of notes that I seem unable to ever fully vanquish.

The Last Book Box

In a post six years ago I mentioned that I’d finally gotten around to unpacking a box of books that had been sitting in a closet since I moved into the place. The problem I always have when I move (aside from all the book packing) is shelf space. I prefer the kind of shelves mounted on the wall, so I have to recreate shelf space every time.

In a post six years ago I mentioned that I’d finally gotten around to unpacking a box of books that had been sitting in a closet since I moved into the place. The problem I always have when I move (aside from all the book packing) is shelf space. I prefer the kind of shelves mounted on the wall, so I have to recreate shelf space every time.

Not that my memory for what I mentioned in a post six years ago is sharp. Or even exists. I noticed the post had some views recently, so I re-read it. The line caught my eye because last week I opened the last unopened box of books.

And I found some old science fiction friends!

Ellis: Axiom’s End

I actively try to avoid “the buzz” — for most definitions of the word (“beer buzz” is a whole other thing than I’m talking about here). I mean the buzz of current memes and all the popular things I’m supposed to think, feel, and be. As I’ve said before, I’m deliberately allergic to trendy — I refuse to swim in the main stream.

I actively try to avoid “the buzz” — for most definitions of the word (“beer buzz” is a whole other thing than I’m talking about here). I mean the buzz of current memes and all the popular things I’m supposed to think, feel, and be. As I’ve said before, I’m deliberately allergic to trendy — I refuse to swim in the main stream.

That applies especially to the books, TV shows, or movies, that I’m supposed to see. I’m even more resistant to things I’m supposed to either hate or love. (I still have never seen ET — never will.) I generally don’t read or watch reviews until after I’ve read or watched what they review.

Which brings me to Axiom’s End (2020) a debut novel by Lindsay Ellis.

Morell: Animal Wise

I recently read Animal Wise: How We Know Animals Think and Feel (2013) by Virginia Morell, correspondent for Science and contributor to National Geographic, Smithsonian, and other publications. She’s author of several books including Wildlife Wars (2001), which she co-authored with Richard Leakey.

I recently read Animal Wise: How We Know Animals Think and Feel (2013) by Virginia Morell, correspondent for Science and contributor to National Geographic, Smithsonian, and other publications. She’s author of several books including Wildlife Wars (2001), which she co-authored with Richard Leakey.

Morell takes us on a tour of current research into the minds of animals, starting with ants and working up through various species to our primate relatives. Dear to my heart, she reserves the last chapter for our best friends, dogs.

I found it a wonderful exploration with some real eye-openers.

Old Friends

There are many kinds of “comfort food” we resort to, from actual food — pizza always seemed a good choice in my view — to all the other distractions we use to give ourselves a bit of relief from the stresses of life. (Of course, that sort of thing can become addictive, but that’s another topic.)

There are many kinds of “comfort food” we resort to, from actual food — pizza always seemed a good choice in my view — to all the other distractions we use to give ourselves a bit of relief from the stresses of life. (Of course, that sort of thing can become addictive, but that’s another topic.)

Books have been a life-long escape to joy for me. Some are educational, and I love learning new things, but I think the best escape comes from fiction, and especially those fictions with long-running characters — people one comes to know. Sherlock Holmes, for example, is someone I’ve known for over 50 years.

And so are Hercule Poirot and Perry Mason.

The Expanse: Disappointment

I feel like a jilted lover. Or a very disappointed one. I found what seemed a delightful bit of science fiction color in an otherwise increasingly grey and dismal world. I let myself get attached (despite a few alarm bells going off in my head). I thought I’d found something truly worthwhile — something to invest myself in.

I feel like a jilted lover. Or a very disappointed one. I found what seemed a delightful bit of science fiction color in an otherwise increasingly grey and dismal world. I let myself get attached (despite a few alarm bells going off in my head). I thought I’d found something truly worthwhile — something to invest myself in.

And it seemed really good at first. There was all the excitement of exploring something new and interesting. But after that great start, there came a most unwelcome left turn into a stinking swamp I want no part of.

This isn’t a Sci-Fi Saturday post or a TV Tuesday post… this is a spleen vent.

Passing Time

I just finished Time Travel: A History (2016) by science historian and author James Gleick. The New York Times Book Review, Anthony Doerr described it as, “A fascinating mash-up of philosophy, literary criticism, physics and cultural observation.” I agree with that description minus the word fascinating. I would have said tedious.

I just finished Time Travel: A History (2016) by science historian and author James Gleick. The New York Times Book Review, Anthony Doerr described it as, “A fascinating mash-up of philosophy, literary criticism, physics and cultural observation.” I agree with that description minus the word fascinating. I would have said tedious.

This is not the book’s fault. I’m not saying it’s bad. There was nothing I disagreed with. There were even a few parts I got into. The problem is I found it ambling, rambling, and meandering. It wasn’t incoherent, but it seemed disconnected to me.

Overall I found it easy to put down and hard to pick back up.

The Subtle Art

A few weeks ago a friend loaned me The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck (2016), by Mark Manson. I just finished it, and — while I’m not a big fan of self-help books — I give this one an Ah! rating. Manson’s approach, contrary to our modern norm, is not about finding happiness, but about choosing the pain worth seeking (and letting the happiness come through our fulfillment).

A few weeks ago a friend loaned me The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck (2016), by Mark Manson. I just finished it, and — while I’m not a big fan of self-help books — I give this one an Ah! rating. Manson’s approach, contrary to our modern norm, is not about finding happiness, but about choosing the pain worth seeking (and letting the happiness come through our fulfillment).

The subtle part is that not giving a f*ck doesn’t mean one stops caring. The subtle part is learning to be selective about what matters to us.

The counterintuitive part is that chasing happiness leads to misery.

Cool Elmore Leonard

For this Mystery Monday I want to tell you about a great American writer whose name you might not know: Elmore Leonard (1925–2013). As with Philip K. Dick, another great American writer, it’s quite possible you’ve seen a movie based on his work without realizing it. In fact, Elmore Leonard gives Stephen King a run for the money when it comes to works adapted to film.

For this Mystery Monday I want to tell you about a great American writer whose name you might not know: Elmore Leonard (1925–2013). As with Philip K. Dick, another great American writer, it’s quite possible you’ve seen a movie based on his work without realizing it. In fact, Elmore Leonard gives Stephen King a run for the money when it comes to works adapted to film.

Two of my very favorite films, Get Shorty (1995) and Jackie Brown (1997), are adaptations of Leonard’s novels. The former is the second film that restarted John Travolta’s career, and many believe the success of the film greatly depends on the source material (I quite agree).

If you like crime fiction, you definitely want to get into Elmore Leonard.

Parker: Humble Pi

I just finished Humble Pi (2019), by Matt Parker, and I absolutely loved it. Parker, a former high school maths teacher, now a maths popularizer, has an easy breezy style dotted with wry jokes and good humor. I read three-quarters of the book in one sitting because I couldn’t stop (just one more chapter, then I’ll go to bed).

I just finished Humble Pi (2019), by Matt Parker, and I absolutely loved it. Parker, a former high school maths teacher, now a maths popularizer, has an easy breezy style dotted with wry jokes and good humor. I read three-quarters of the book in one sitting because I couldn’t stop (just one more chapter, then I’ll go to bed).

It’s a book about mathematical mistakes, some funny, some literally deadly. It’s also about how we need to be better at numbers and careful how we use them. Most importantly, it’s about how mathematics is so deeply embedded in modern life.

It’s my third maths book in a month and the only one I thoroughly enjoyed.

Tegmark: MUH? Meh!

I finally finished Our Mathematical Universe (2014) by Max Tegmark. It took me a while — only two days left on the 21-day library loan. I often had to put it down to clear my mind and give my neck a rest. (The book invoked a lot of head-shaking. It gave me a very bad case of the Yeah, buts.)

I finally finished Our Mathematical Universe (2014) by Max Tegmark. It took me a while — only two days left on the 21-day library loan. I often had to put it down to clear my mind and give my neck a rest. (The book invoked a lot of head-shaking. It gave me a very bad case of the Yeah, buts.)

I debated whether to post this for Sci-Fi Saturday or for more metaphysical Sabbath Sunday. I tend to think either would be appropriate to the subject matter. Given how many science fiction references Tegmark makes in the book, I’m going with Saturday.

The hard part is going to be keeping this post a reasonable length.

Secret Code II

I’ve written about secret codes before. The Pigpen cipher was pretty simplistic, almost more a child’s game, but the Playfair cipher was a bit more interesting. That one came from a murder mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers. Today I thought I’d show you another simple code from another mystery novel.

I’ve written about secret codes before. The Pigpen cipher was pretty simplistic, almost more a child’s game, but the Playfair cipher was a bit more interesting. That one came from a murder mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers. Today I thought I’d show you another simple code from another mystery novel.

1829 2125 0038 2226 1600 2125 0027 1722 4200 1829 1600 4219 2518 1617 1900 4122 3916 3200 3700 4019 0025 2016 0028 1724 2718 2241 4400 2118 0020 2516 2500 1829 1600 1819 2316 1517 2118 1617 0038 2226 1643 0015 2921 3829 0030 2025 1800 2425 2521 2841 2500 4120 4240 1617 2500 1822 0018 2916 0031 1619

Stop! See if you can decode the above before continuing.

Stephenson: D.O.D.O.

Neal Stephenson, like Greg Egan, is a hard science fiction author who never fails to delight me with something new and tasty. Both Stephenson and Egan seem able to leave footprints in otherwise well-trodden ground. Stephenson, in particular, often makes me LOL.

Neal Stephenson, like Greg Egan, is a hard science fiction author who never fails to delight me with something new and tasty. Both Stephenson and Egan seem able to leave footprints in otherwise well-trodden ground. Stephenson, in particular, often makes me LOL.

That’s not an acronym I use very often, but it seems especially appropriate here given this post is about The Rise and Fall of D.O.D.O., by Neal Stephenson and Nicole Galland. The book has so many tongue-in-cheek military acronyms (DODO, DTAP, DEDE, MUON, etc) that it has a glossary at the back.

The story concerns parallel worlds, wave-function collapse, and witches.

Wynne: Dog is Love

Recently I read Dog is Love, Why and How Your Dog Loves You (2019), by Clive D.L. Wynne, an animal behavior scientist who specializes in dogs. Despite the loaded word “love” in the title, this is a science book about a search for hard evidence.

Recently I read Dog is Love, Why and How Your Dog Loves You (2019), by Clive D.L. Wynne, an animal behavior scientist who specializes in dogs. Despite the loaded word “love” in the title, this is a science book about a search for hard evidence.

Dr. Wynne is a psychology professor at Arizona State University and director of their Canine Science Collaboratory. He’s written several other books about animal cognition: The Mental Lives of Animals (2001), Do Animals Think (2004), Evolution, Behavior and Cognition (2013).

The book is the story of Wynne’s search for exactly what it is that makes dogs special and how they got that way.

Manifold: Trilogy

Recently I posted about Manifold: Time, the first book in a trilogy by Stephen Baxter, a writer new to me. As I wrote, I wasn’t very whelmed, but a bad meal at a new restaurant can be a fluke — it’s only fair to give the chef at least one more chance. (A single data point doesn’t mean much.) And I did find the overall themes a little intriguing.

Recently I posted about Manifold: Time, the first book in a trilogy by Stephen Baxter, a writer new to me. As I wrote, I wasn’t very whelmed, but a bad meal at a new restaurant can be a fluke — it’s only fair to give the chef at least one more chance. (A single data point doesn’t mean much.) And I did find the overall themes a little intriguing.

As it turned out, I rather enjoyed the second one, Manifold: Space. The story stayed grounded and engaged me throughout, plus there were several cool science fiction ideas I’d never encountered before (which is kinda the point of reading hard SF). So a definite thumbs up on book number two.

Unfortunately the third book, Manifold: Origin, didn’t do much for me.

Fairy Tale Physics

My voracious reading habit has deep roots in libraries. The love of reading comes from my parents, but libraries provided a vast smörgåsbord to browse and consume. Each week I’d check out as many books as I could carry. I discovered science fiction in a library (the Lucky Starr series, with Isaac Asimov writing as Paul French, is the first I remember).

My voracious reading habit has deep roots in libraries. The love of reading comes from my parents, but libraries provided a vast smörgåsbord to browse and consume. Each week I’d check out as many books as I could carry. I discovered science fiction in a library (the Lucky Starr series, with Isaac Asimov writing as Paul French, is the first I remember).

Modern adult life, I got out of the habit of libraries (and into book stores and now online books). But now the Cloud Library has reinvigorated my love of all those free books, especially the ones I missed along the way.

For instance, Farewell to Reality: How Modern Physics Has Betrayed the Search for Scientific Truth (2014), by Jim Baggott.

Joe, Jim and Bernie

Yá’át’ééh! Fans of the Hillerman books will immediately recognize the three names in the title as Joe Leaphorn, Jim Chee, and Bernadette Manuelito (a relatively new addition who doesn’t yet have her own Wiki page). All three are (fictional) police officers working for the (real) Navajo Tribal Police in the American southwest.

Yá’át’ééh! Fans of the Hillerman books will immediately recognize the three names in the title as Joe Leaphorn, Jim Chee, and Bernadette Manuelito (a relatively new addition who doesn’t yet have her own Wiki page). All three are (fictional) police officers working for the (real) Navajo Tribal Police in the American southwest.

I have to call them just “the Hillerman books” now, because after father Tony Hillerman died, daughter Anne Hillerman took up the series and has so far contributed five very worthy stories of her own. (Her vision of the series puts Bernie Manuelito front and center and thus adds fresh air to the 18 books her father wrote.)

I’m a fan of detective novels, especially murder mystery detective novels, and these are without question my second favorite mystery books of all time.

Stephen Baxter: Manifold

Yesterday, courtesy of Cloud Library, I finished Manifold: Time (1999), by Stephen Baxter. It’s my first exposure to Baxter, who has written 60 science fiction novels — none of which I’ve read. Per his Wiki bibliography, he’s written only a half-dozen short stories, also none of which I’ve read. (There are SF authors I’ve only met in short story collections. He isn’t one of them.)

Yesterday, courtesy of Cloud Library, I finished Manifold: Time (1999), by Stephen Baxter. It’s my first exposure to Baxter, who has written 60 science fiction novels — none of which I’ve read. Per his Wiki bibliography, he’s written only a half-dozen short stories, also none of which I’ve read. (There are SF authors I’ve only met in short story collections. He isn’t one of them.)

Time is the first of the Manifold trilogy (which has a fourth book, Phase Space); the second and third books are Space (2000) and Origin (2001). Each of the books tells a separate story in a separate universe.

I enjoyed the first book, but I can’t say I was hugely whelmed.

Fall: or, Dodge in Hell

I finished Fall: or, Dodge in Hell, the latest novel from Neal Stephenson, and I’m conflicted between parts I found fascinating and thoughtful and parts I found tedious and unsatisfying. This division almost exactly follows the division of the story itself into real and virtual worlds. I liked the former, but the latter not so much.

I finished Fall: or, Dodge in Hell, the latest novel from Neal Stephenson, and I’m conflicted between parts I found fascinating and thoughtful and parts I found tedious and unsatisfying. This division almost exactly follows the division of the story itself into real and virtual worlds. I liked the former, but the latter not so much.

Unfortunately, at least the last third of the book involves a Medieval fantasy quest that takes place in the virtual reality. The early parts of the story in the VR are fairly interesting, but the quest really left me cold, and I found myself skimming pages.

I give it a positive rating, but it’s my least-liked Stephenson novel.

Neal Stephenson

I’ve been a fan of Neal Stephenson since Snow Crash (1992), his third novel. I’ve read much of his work — the big exception being The Baroque Cycle, descriptions of which haven’t captured my interest yet. I like his writing enough that I’ll probably enjoy them if I ever take the plunge.

I’ve been a fan of Neal Stephenson since Snow Crash (1992), his third novel. I’ve read much of his work — the big exception being The Baroque Cycle, descriptions of which haven’t captured my interest yet. I like his writing enough that I’ll probably enjoy them if I ever take the plunge.

Stephenson writes pretty hard SF, which I love, and he explores such interesting ideas that I’m generally quite enthralled by what some see as fictionalized physics books. The thing is, I’d enjoy reading those physics books, so having it come coated in any kind of frosting is a win in my (pardon the pun) book.

I’ve just gotten started on his most recent novel, Fall; or, Dodge in Hell.

Nero and Archie

Science fiction has been a deep part of my life since I was a child. I discovered it early and have been reading it ever since I started picking my own reading material. As a consequence, I’ve written a lot of posts on various SF topics, but somehow I’ve never gotten around to writing much about my other favorite genre: detective stories.

Science fiction has been a deep part of my life since I was a child. I discovered it early and have been reading it ever since I started picking my own reading material. As a consequence, I’ve written a lot of posts on various SF topics, but somehow I’ve never gotten around to writing much about my other favorite genre: detective stories.

As with the SF, I discovered Sherlock Holmes early, along with the Agatha Christie detectives, Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot. I fell in love with the idea of the puzzle-solving detective. (I also had a crush on Nancy Drew, but that was a whole other kind of interest.)

Then my dad, who also loved mysteries, introduced me to Rex Stout…

A Bit of Huang and Laurie

For a Sci-Fi Saturday post, this started as a stretch and then some. While Zero Sum Game (2018), by S.L. Huang, has at least a science fiction flavor, The Gun Seller (1996), by Hugh Laurie (yes, that Hugh Laurie), is more fantastical than science fictional. They do have in common a protagonist beyond capable as well as action hero thriller plots.

For a Sci-Fi Saturday post, this started as a stretch and then some. While Zero Sum Game (2018), by S.L. Huang, has at least a science fiction flavor, The Gun Seller (1996), by Hugh Laurie (yes, that Hugh Laurie), is more fantastical than science fictional. They do have in common a protagonist beyond capable as well as action hero thriller plots.

I can redeem the post now that I’ve read The Android’s Dream (2006), by John Scalzi (whom I’ve praised here before for Redshirts). Here, too, is an extremely competent protagonist in an action hero thriller. (As an aside, the two written by men feature a love interest. (While I’m at it, guess which of the three does not have a Wiki page.))

The bottom line: I thoroughly enjoyed all three!

Scalzi: Redshirts

I just finished reading Redshirts, by John Scalzi, and it’s just about the best, most entertaining, brilliant story I’ve read in a good long time. It’s so good that I have to place it with other best-of-kind laugh out loud science fiction delights such as Galaxy Quest and Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

I just finished reading Redshirts, by John Scalzi, and it’s just about the best, most entertaining, brilliant story I’ve read in a good long time. It’s so good that I have to place it with other best-of-kind laugh out loud science fiction delights such as Galaxy Quest and Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

It has a lot in common with Galaxy Quest in being a multi-level utterly ingenious send up and hysterical deconstruction of Star Trek (The Original Series). Scalzi has captured and lampshaded so many of the things fans have discussed over the years. And, as with Galaxy Quest, it’s a pretty good story all on its own.

But it is an absolute must-read for any fan of the original Star Trek.

Dark Run & Ball Lightning

Recently I’ve dedicated myself to catching up on my reading list. Various life distractions have caused me to not read nearly as much as I used to. Actually, it’s more that I haven’t been reading fiction that much lately; I’ve been more focused on news feeds and science (articles and books). I find I miss curling up for hours with a good story, so I’ve determined to return to it.

Recently I’ve dedicated myself to catching up on my reading list. Various life distractions have caused me to not read nearly as much as I used to. Actually, it’s more that I haven’t been reading fiction that much lately; I’ve been more focused on news feeds and science (articles and books). I find I miss curling up for hours with a good story, so I’ve determined to return to it.

Here for Sci-Fi Saturday I thought I’d mention a couple I finished this past week: Ball Lightning, by Liu Cixin, and Dark Run, by Mike Brooks. The former is a standalone novel; the latter is the first (of so far three) in a series.

The Brooks books are sheer adventure yarns, but telling you about Ball Lightning requires a pretty hefty spoiler.

Greg Egan: Quarantine

Last week I read Quarantine (Greg Egan, 1992), a science fiction novel that explores one of the more vexing conundrums in basic physics: the measurement problem. Egan’s stories (novels and shorts) often explore some specific aspect of physics (sometimes by positing a counterfactual reality, as in the Orthogonal series).

Last week I read Quarantine (Greg Egan, 1992), a science fiction novel that explores one of the more vexing conundrums in basic physics: the measurement problem. Egan’s stories (novels and shorts) often explore some specific aspect of physics (sometimes by positing a counterfactual reality, as in the Orthogonal series).

In Quarantine, Egan posits that the human mind, due to a specific set of neural pathways, is the only thing in reality that collapses the wave-function, the only thing that truly measures anything. All matter, until observed by a mind, exists in quantum superposition.

Unfortunately, it’s difficult to explore how this ties into the plot without spoiling it, so I’ll have to tread lightly.

Time and Two Doors

In the last week or so I read an interesting pair of books: Through Two Doors at Once, by author and journalist Anil Ananthaswamy, and The Order of Time, by theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli. While I did find them interesting, and I’m not sorry I bought them (as Apple ebooks), I can’t say they added anything to my knowledge or understanding.

In the last week or so I read an interesting pair of books: Through Two Doors at Once, by author and journalist Anil Ananthaswamy, and The Order of Time, by theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli. While I did find them interesting, and I’m not sorry I bought them (as Apple ebooks), I can’t say they added anything to my knowledge or understanding.

I was already familiar with the material Ananthaswamy covers and knew of the experiments he discusses — I’ve been following the topic (the two-slit experiment) since at least the 1970s. It was nice seeing it all in one place. I enjoyed the read and recommend it to anyone with an interest.

I had a little trouble with the Rovelli book, perhaps in part because my intuitions of time are different than his, but also because I found it a bit poetic and hand-wavy.

Our Existence (part 1)

I’m not quite halfway through Existence, by David Brin, but I’m enjoying it so much I have to start talking about it now. For one thing, it’s such a change from the Last Chronicles, which was a hard slog with a disappointing ending. (Still worth the journey, though.)

I’m not quite halfway through Existence, by David Brin, but I’m enjoying it so much I have to start talking about it now. For one thing, it’s such a change from the Last Chronicles, which was a hard slog with a disappointing ending. (Still worth the journey, though.)

The novel is a standalone, not part of his Uplift Universe, but it apparently can be viewed as a kind of prequel to that reality. However: so far no alien contact, humanity is still on Earth, and computers are not conscious (but AI is very, very good). The year, as far as I can tell, seems to be in the 2040s or 2050s.

At heart, the novel’s theme is the Fermi Paradox; it examines many of the potential Great Filters that might end an intelligent species. But now an alien artifact has been found, a kind of message in a bottle that appears to contain a crowd of alien minds…

Our Existence (part 2)

Recently I wrote that I was reading Existence (David Brin, 2012), a novel I found so striking I had to post about it before I was even halfway through. Now I’ve finished it, and I still think it’s one of the more striking books I’ve read recently. (Although a little blush came off the rose in the last acts.)

Recently I wrote that I was reading Existence (David Brin, 2012), a novel I found so striking I had to post about it before I was even halfway through. Now I’ve finished it, and I still think it’s one of the more striking books I’ve read recently. (Although a little blush came off the rose in the last acts.)

Central to the story is the Fermi Paradox, with a focus on all the pitfalls an intelligent species faces. The tag line of the book, a quote attributed to Joseph Miller, is, “Those who ignore the mistakes of the future are bound to make them.” Brin’s tale suggests that it’s well neigh impossible for an intelligent species to survive their own intelligence.

I’ll divide this post into three parts: Mild spoilers; Serious spoilers; and Giving-away-the-ending spoilers. I’ll warn you before each part so you can stop reading if you choose.

Fantasy Chronicles

Earlier this week I posted about all the TV (5.0!) that I watched while dog-sitting Bentley. There I mentioned how days were allocated to reading in hopes of reducing what has grown to be a rather long To-Read list. (Not to mention the books in my To-Buy list; I really do need to spend more time reading.)

Earlier this week I posted about all the TV (5.0!) that I watched while dog-sitting Bentley. There I mentioned how days were allocated to reading in hopes of reducing what has grown to be a rather long To-Read list. (Not to mention the books in my To-Buy list; I really do need to spend more time reading.)

Central to the plan was, at long last, finishing The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, by Stephen R. Donaldson. Specifically, finishing The Last Chronicles, the third (presumably final) set of the series (“set” because while the first two were trilogies, the third is a tetralogy, with four books).

Unfortunately, for various reasons (or various naps), I only managed to get halfway through the second book.

Greg, Neal, and Hannu

Fair Warning: Next week I have some political and social foaming at the mouth to do over current events and modern society, but that can wait. The weather recently has been too nice for my hot-collar wardrobe. The swelter is supposed to return next week; the forecast is for serious ranting with scattered raving.

Fair Warning: Next week I have some political and social foaming at the mouth to do over current events and modern society, but that can wait. The weather recently has been too nice for my hot-collar wardrobe. The swelter is supposed to return next week; the forecast is for serious ranting with scattered raving.

For the weekend, for Science Fiction Saturday in particular, for all my disdain of movie and TV science fiction (especially TV SF, most of which does nothing for me), literary science fiction is very alive and quite well!

Recently I’ve been enjoying three authors in particular…

Pterry Psnippets #1

As a memorial to the loss of my favorite voice in fiction, I’ve been doing a Sir Terry Pratchett Discworld memorial read. I’d been planning to read the Witches novels again anyway, so I did that and then went on to read the Rincewind novels. Now I’m working my way through the rest in chronological order. I just finished Hogfather.

As a memorial to the loss of my favorite voice in fiction, I’ve been doing a Sir Terry Pratchett Discworld memorial read. I’d been planning to read the Witches novels again anyway, so I did that and then went on to read the Rincewind novels. Now I’m working my way through the rest in chronological order. I just finished Hogfather.

This time, as I go, I’m leaving tape flags behind to mark bits I especially liked and plan to share (and record) here. Part of what is so engaging about the Discworld novels is how intelligent and perceptive the writing is. Pratchett was a brilliant writer. After reading these books many times I’m still learning to appreciate his genius.

Today I thought I’d share some of those flagged bits with you.

Frogs of Fantasy

For my money, Sir Terry Pratchett is the greatest fantasy author ever. That includes Tolkien, Verne, Wells, Burroughs, and Howard. (Martin isn’t even in this conversation to my mind, but then neither is Lucas.) Pratchett’s work has incredible social relevance. His keen sense of people, his deft hand with humor, and his ability to weave a rich, textured story as engaging as it is fantastic, gives his work a substance that sticks to the soul.

For my money, Sir Terry Pratchett is the greatest fantasy author ever. That includes Tolkien, Verne, Wells, Burroughs, and Howard. (Martin isn’t even in this conversation to my mind, but then neither is Lucas.) Pratchett’s work has incredible social relevance. His keen sense of people, his deft hand with humor, and his ability to weave a rich, textured story as engaging as it is fantastic, gives his work a substance that sticks to the soul.

A recurring theme in Pratchett is the power — and the reality — of belief. Is Superman real? Or Sherlock Holmes? If millions believe in them, if so many stories are told about them, how can they not be real? One might say the same of all the gods we worship.

There’s also the bit about the frogs.

Sunday Soul Music

Earlier this week I finished re-reading what might be my favorite Terry Pratchett Discworld novel, Soul Music. When I introduced you to Pratchett and Discworld I mentioned that each novel has its own theme. Nearly all the novels use the same groups of characters, but each revolves around a unique theme (and usually one of the character groups, although cross-over is frequent).

Earlier this week I finished re-reading what might be my favorite Terry Pratchett Discworld novel, Soul Music. When I introduced you to Pratchett and Discworld I mentioned that each novel has its own theme. Nearly all the novels use the same groups of characters, but each revolves around a unique theme (and usually one of the character groups, although cross-over is frequent).

Soul Music is about “music with rocks in it” (in other words: rock music). It’s technically one of the “Death” novels (which is to say that the Discworld avatar of Death is the main character), but it prominently features the Wizards in supporting roles.

And Death’s grand-daughter, Susan. And the spirit of Buddy Holly.

The Colour of Magic

I’ve spent the last two weekends (and many weekday evenings) with an old, dear friend in a magical place. I can no longer remember how I found the place or how I was introduced to my friend. I do know that this year marks the 30-year anniversary of its founding. I think I’ve been here since the beginning. If not, it wasn’t long after.

I’ve spent the last two weekends (and many weekday evenings) with an old, dear friend in a magical place. I can no longer remember how I found the place or how I was introduced to my friend. I do know that this year marks the 30-year anniversary of its founding. I think I’ve been here since the beginning. If not, it wasn’t long after.

So I’ve known and loved this place, and my friend, for long time. Remarkably, the charm has never left it. For three decades (or so) it has delighted me, impressed me, moved me and made me laugh out loud. It is for me the finest of the finest, my favorite favorite. There is none better and very few that come close.

I’m speaking of Terry Pratchett‘s wonderful Discworld books.

A Christmas Carol

Most of us have traditional ways of celebrating or observing the re-occurring events in our lives. An anniversary might call for dinner at a certain restaurant. A promotion or sale might call for buying a round of drinks. The great life milestones — births, graduations, weddings, retirements, deaths — all come heavily freighted with traditional behaviors.

Most of us have traditional ways of celebrating or observing the re-occurring events in our lives. An anniversary might call for dinner at a certain restaurant. A promotion or sale might call for buying a round of drinks. The great life milestones — births, graduations, weddings, retirements, deaths — all come heavily freighted with traditional behaviors.

For me, an important tradition at Christmas time is watching — and reading — the Charles Dickens classic, A Christmas Carol! I think it is one of the most engaging, endearing, wonderful and important stories ever. It is a story of redemption and re-discovery of lost joy. And it is an affirmation that how we choose to live our lives matters.

Plus it has ghosts!

SF: Distress by Greg Egan

It’s official, I really like science fiction author Greg Egan! He’s among the modern science fiction authors; his first SF work, the short story Artifact, was published in 1983, so he’s been writing SF for about 28 years. Like many science fiction authors with a science or technical education, he writes non-fiction as well.

It’s official, I really like science fiction author Greg Egan! He’s among the modern science fiction authors; his first SF work, the short story Artifact, was published in 1983, so he’s been writing SF for about 28 years. Like many science fiction authors with a science or technical education, he writes non-fiction as well.

And here’s the thing: If you like your science fiction hard, you want to know about Greg Egan. He writes SF as hard as any I know. For instance, consider a novel (Incandescence) in which a key plot thread involves alien beings discovering (Einstein’s) General Relativity in a completely different way than Einstein did.