The old saying “Spare the rod, spoil the child” has fallen into, shall we say, severe disfavor these days, even as just a metaphor for strict childrearing. And forget about actually spanking your kid — that’s child abuse by modern standards.

The old saying “Spare the rod, spoil the child” has fallen into, shall we say, severe disfavor these days, even as just a metaphor for strict childrearing. And forget about actually spanking your kid — that’s child abuse by modern standards.

At the same time, we seem to be in the midst of a serious and growing mental health crisis among teens, especially in the USA (but also the UK and Australia).

A new book by Abigail Shrier suggests these may be connected.

The book is Bad Therapy: Why the kids aren’t growing up, and it was published less than a week ago (on February 27, 2024). I haven’t read it — childrearing being something of a moot point for me, at least personally — but the review in the current issue of New Scientist caught my eye over breakfast this morning.

[The articles seem to require creating an account, which I don’t need to do because I read the magazine through my Libby library app, so I don’t know if registering allows free access or if there is a paywall to deal with. I’ll quote some relevant bits.]

Shrier is a former opinion columnist for the Wall Street Journal and has one previous book: Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters (2020). The book was, to say the least, controversial. It received strong criticism from both scientific and social sources but has also received strong support.

I have even less to say about transgender than I do about childrearing, both topics being almost entirely outside my experience. The one observation I can make is that the former is yet another social topic we seem unable to discuss honestly. (Comedian Dave Chappell generated major waves just joking about it. Not only can’t we discuss it honestly, we’re not even allowed to joke about it. Which seems tragic to me.)

But this isn’t about that, and I mention Shrier’s first book only to point out that, firstly, she seems to be a controversial author, secondly, she seems to have a conservative slant (if that matters to you), and thirdly, and most importantly, her books are opinion pieces. So, a shaker of salt should be taken with her writing.

That said, there does seem a possible grain of truth. Much of what was in the review of her new book seemed worth consideration. Shrier points to “helicopter parenting” in contrast to the more hands-off approach most adults today remember from their own childhood:

In the past, children didn’t spend a large part of the day being taxied from one stimulating activity to another, but were left to get bored, make up games and rub along with the local kids, being socialised in the process. Their squabbles and scrapes helped foster resilience and turn them into functioning adults, she writes.

The reviewer goes on to say:

Another of Shrier’s targets is the vogue for “gentle parenting”. Previous generations “corrected and punished their way through childrearing”. Today we talk to our kids in the language of therapists, which Shrier satirises as: “Sammy, I see that you’re feeling frustrated. Is there a way you could express your frustration without biting your sister?”

[New Scientist is published in London, hence the British spelling of socialized and satirizes.]

Shrier also targets “therapy-speak” (and “therapy-think”) as a part of a growing negative influence of the mental health industry on family and childhood. One does have to wonder if — despite their clear value in many situations — we haven’t sometimes gone a bit overboard with medication and therapy. What once were seen as just variations in how humans are now are viewed as syndromes to be corrected.

Bottom line, while admittedly Shrier is going by anecdotal evidence and opinion, and also admittedly, sociology is notoriously difficult, but, as New Scientist reviewer, Clare Wilson, concludes, “If only a tenth of what Shrier writes is correct, it would be profoundly alarming.”

Which, I think, is probably the right way to look at it. As with Shrier’s first book, perhaps the value lies in the conversation and thought it can provoke.

That we are seeing a rise in mental health issues in teens seems undeniable. But, as with most social aspects, there are probably myriad contributing factors.

Many have pointed to social media as a source of angst among the young. The problem doesn’t seem to be internet use in general, but with the social media platforms with high engagement. Many feel a strong sense of FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) as well as a strong sense of not measuring up to the supposedly dynamic and exciting lives presented on such platforms.

It’s also possible we’re just getting better at diagnosing mental health issues, as well as being more ready to accept them, but it’s also possible we’ve gone too far along that axis.

Our inadequate education system may also account for some of it. Even the fears of the future induced by population growth, climate change, and economic disparity may be a factor. And one has to wonder what the young make of politics these days.

Bottom line, I think in today’s world, it’s really hard to be a young person.

Hang in there, my friends! Go forth and spread beauty and light.

∇

March 4th, 2024 at 4:15 pm

And interesting element of irony here if our efforts to protect our children have actually put them at risk.

March 5th, 2024 at 10:24 am

“in today’s world, it’s really hard to be a young person.”

No doubt. However, also to be a parent. We’ve all been “a young person” so can relate to that; but not in the age of social media, the Internet, and smart phones. Having raised a Millennial son, and been step-parent to two Gen X daughters – I can say, I don’t know what I’d do today w/r/t the technology and children. I think, overall, it has a negative impact on everyone! And society in general. (As does my psych-girl.)

Anyway – Shrier was on Joe Rogan’s podcast, and there are many clips on Youtube. Did you see any?

March 5th, 2024 at 12:45 pm

Yeah, being a parent is a tough gig, too. When I was young, my parents put limits on how much TV we could watch as well as what we could watch. I remember hanging out at a friend’s house and watching “forbidden” Saturday afternoon movies such as “Hercules and the Ant-Men.”

Sorry, but hard pass on Joe Rogan. And my interest in the topic amounts to “hardly any”. (But isn’t it fun how you can find almost anything on YouTube!) I just thought it was interesting that someone was pushing back on modern childrearing. But I got no dog in that hunt, myself. 😃

March 5th, 2024 at 11:17 am

I’m in the same boat as you in not having kids myself, but helicopter parenting is everywhere and it’s driving me nuts. At the same time where are the parents when their misbehaving kid is getting on my nerves? Suddenly poof. Go figure. The problem is that I don’t feel comfortable telling the kid off because our standards for that sort of thing are so very different from when I was growing up. It used to be that the adult in the room had the final say, but now it’s the kid who has the final say. The kid is always right, their feelings are the only thing that matters. This factors into education in a major way.

March 5th, 2024 at 12:59 pm

Heh, yeah, totally. As we were just talking about, the education system is pretty broken right now.

A while back, while dog sitting Bentley, there were some young kids (visitors, I think) playing outside the next-door condo (which shares a common wall with my living room). Their play had them around the projecting privacy wall and onto the small concrete slab that calls itself my patio. Bentley was going nuts, so I gave them a piece of my mind, and they looked at me like they had no clue. Which, obviously, they didn’t.

I’ve noticed when taking walks that the younger the person I walk past (someone going the other way), the less likely that they’ll even acknowledge my existence, let alone smile or say “Hi.” I think one consequence of social media and the forever-online generation is a stunning lack of social graces and manner. Even the generation raising them seems pretty clueless.

(Aside: Why, oh, why are bathroom, bedroom, and storeroom single words while living room and dining room are two? At least according to my spellchecker. I wonder if it’s to remove the possibility of reading “groom” — livin’ groom and dinin’ groom. Where’s the bride?)

March 5th, 2024 at 1:13 pm

Funny, I’ve noticed the same thing about people walking, although there have been a few delightful exceptions: a 10 year old kid on a bike wearing a hilarious mohawk helmet said “good morning” to me, and the fact that I was shocked says a lot about my expectations these days.

“Aside: Why, oh, why are bathroom, bedroom, and storeroom single words while living room and dining room are two?”

There’s something I’ve never thought about. I have no idea!

March 5th, 2024 at 7:51 pm

Is it a rise truly? I think that we let youth talk about gender, sexuality and mental health challenges. As a Gen Xer I just kept my head down and stuffed all emotion. I think when we give voice to what youth are struggling with, it can be a relief for them.

March 6th, 2024 at 8:21 am

Apparently, yes. According to the US Surgeon General’s report from 2021, “the challenges today’s generation of young people face are unprecedented and uniquely hard to navigate. And the effect these challenges have had on their mental health is devastating.”

The report continues, “Recent national surveys of young people have shown alarming increases in the prevalence of certain mental health challenges—in 2019, one in three high school students and half of female students reported persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, an overall increase of 40% from 2009.” Reports of self-harm, thoughts of suicide, plans for suicide, and actual suicide show rising statistics: “Between 2007 and 2018, suicide rates among youth ages 10-24 in the US increased by 57%.”

Per the review in New Scientist, Shrier tells about how, “when she took her 12-year-old to the doctor with a stomach ache, he was asked questions such as whether he ever felt his family would be better off if he were dead. US schools also routinely use such surveys to ask children if they think of cutting or burning themselves. No one seems to consider the potential for putting ideas in their heads.”

So, I’d say it’s one thing to listen and pay attention to what our kids are saying about their thoughts and perceptions, but there may be some risk in trying to lead the conversation. As we discussed recently, the human brain isn’t fully baked until somewhere in the mid-20s, and children are thus highly suspectable to influences from people they trust. There is, perhaps, something to be said for preserving some of the innocence of childhood, as challenging as that is these days.

March 6th, 2024 at 9:04 am

Listening non-judgementally and refraining from advice is something all adults could work on!

March 6th, 2024 at 9:08 am

Indeed!

March 7th, 2024 at 6:26 pm

I am finally finishing “Far from the Tree.” Two chapters from now is the “Transgender” chapter and I trust Solomon to have a well-founded account. Will comment here again

March 8th, 2024 at 9:26 am

Sure, if you want. I’d never heard of Solomon or his books. Wiki says he’s an author and LGBTQ activist, and his book sounds to be largely anecdotal, so (being a physics and math guy) I’d tend to take him with the same saltshaker I do Shrier. Certainly no harm in hearing from both sides!

March 8th, 2024 at 9:40 am

Nope. This one is all qualitative research backed up by science.

March 8th, 2024 at 11:21 am

Oh, okay. I was just going off what it said on his website: “Drawing on forty thousand pages of interview transcripts with more than three hundred families, Solomon mines the eloquence of ordinary people facing extreme challenges.” There wasn’t anything scientific studies or papers — it’s described as being more about compelling life stories. It does seem clear he’s an LGBTQ activist. Nothing wrong with that, but it does (to me) suggest his views aren’t necessarily balanced. I’ll defer to your reading of the book, though. I’m just going off what I saw on his website and the Wiki articles.

March 9th, 2024 at 6:13 pm

It’s one chapter. The ones on Autism and Schizophrenia for example, and the author is neither, have 73 and 58 citations alone. And his Bibliography is 76-pages long. Yes, he’s gay, but that isn’t the slant of this book with many topics. It’s about identity being different than that of our parents

March 10th, 2024 at 10:45 am

The author’s sexual orientation isn’t relevant to me. His being an activist is. My experience is that activism rarely comes with a balanced view of both sides of an issue. As an antiauthoritarian skeptic, the “trappings of authority” don’t speak to me — there are too many examples where presumed experts and authorities have gotten it wrong. What speaks to me is content and balance.

So, what has the author written that you find compelling? What do you take away and value? Has any of it changed the way you think? Do you agree with every word, or has any of it raised your eyebrows? Do you think he’s “preaching to the choir” or is it likely those who need to hear his message will read and learn?

As an aside: My identity was certainly different from my parents. I was adopted, and it became clear to me early that I was cut from different cloth. Literally, in the genetic sense. There was no lack of love, and certainly parts of them exist in me, but my mind and worldview are significantly different from theirs. I think it’s something of a given that personal identity is, well, personal and particular to the individual.

March 10th, 2024 at 10:54 am

It’s the way in which he has illustrated that identity isn’t just genetic and that exceptionality comes almost forcefully from within. The “Prodigy” chapter was fascinating

March 10th, 2024 at 11:35 am

Oh, mos def. Identity is almost entirely a social construct, whereas being a prodigy is almost entirely genetic — a talent rather than an acquired skill. (The different cloth I referred to was that I was something of a prodigy, so I’ve experienced that from the inside.) Did the book inform you of these or affirm what you already knew?

March 10th, 2024 at 11:45 am

Some of his thesis that he added evidence to is that identity is actually something only from within. Like a drive and so compelling that the child is driven to fulfill it at the expense of family and friends

March 10th, 2024 at 12:14 pm

Identity is certainly personal. We might be using the term differently, since I would say identity is formed over time and very prone to social influences. The brain isn’t fully baked until one’s mid-20s, so I would think identity likewise takes time to grow and mature. (Mine has certainly evolved over time.) In contrast, talents are innate from birth (Mozart being kind of a canonical example).

March 6th, 2024 at 9:29 am

We’re around the same age, and my father did not “spare-the-rod”. Which was not common in the 50’s. Today it would be considered child abuse.

Myself – the thought to strike, spank, whip any of my children (in the 70’s & 80’s) never crossed my mind. It was difficult to navigate proper and effective discipline. We were entering the age of “therapeutic narcissism”.

I walk in “Open Space” daily. For the most part, wilderness ethics apply – you make eye contact and smile, nod, or say “hi”. It’s “friend or foe”. But not with the young – they don’t. They have a hostile (defensive) vibe. Weird s**t going on.

And now, there’s an armed guard at the entrance to the supermarket!

March 6th, 2024 at 10:04 am

We do seem to live in a fraught and over-wrought time. Given our early school experience, who could have predicted metal detectors in grade schools.

I’ve long thought our current narcissism dates back to the “Me” decade, the 1980s. I think it was a reaction to the hippie decade, the 1960s, which preached (and sometimes even practiced) selflessness (I believe Buddhism became popular in the USA then, as did TM, Zen, and other forms of selflessness). The pendulum swings from one extreme to the other. We seem unable to ever let it come to rest in the moderate sensible center.

That said, if you were a young person in the world today, facing climate change and economic hopelessness, and realized it was due to the generations before you fucking up the world good and proper, you might be hostile, too. Our generation, past generations in general, have a lot to answer for.

As an aside, your comment here is #18,000 on this blog! (This one, then, should be #18,001.)

March 6th, 2024 at 2:30 pm

And, when robots are raising our young, they, the robots, won’t be allowed to be at all “strict”. Kids will push parent-bots around, the bots will report the abusive behavior to the parents who will start to dial back the guardrails. “Yeah, go ahead and slap the little shit, just don’t leave a mark (or scar).”

March 7th, 2024 at 8:18 am

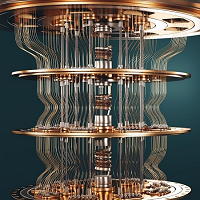

I think we could say that the (virtual) robots already are raising our kids! And actual working robot bodies do already exist — some are in the workplace — but they’re really expensive. (If I had $80K to toss around, I’d buy one of those Spot robot dogs from Boston Dynamics!)