The weather has been so weirdly warm this month that I never got around to a Friday Notes for February, so I’m extending the month. Call it a leap year “plus one”. Truth is, I’m at long last finally starting to reach the bottom of my pile. A lot of what’s left is trivial, silly, or outdated, and I may end up doing a thorough spring cleaning on them.

The weather has been so weirdly warm this month that I never got around to a Friday Notes for February, so I’m extending the month. Call it a leap year “plus one”. Truth is, I’m at long last finally starting to reach the bottom of my pile. A lot of what’s left is trivial, silly, or outdated, and I may end up doing a thorough spring cleaning on them.

The ultimate goal is for the Notes to be about contemporaneous things rather than from old notes that have been fermenting in the pile.

But for a bit longer, it’ll be a combination of both, so off we go.

Some notes that didn’t make it into my recent post, The Irrational Square (because I forgot I’d jotted them down while thinking about the post — even when I write things down, I forget them):

Squares are cool because they’re the quintessential expression of two-dimensional space. They’re part of a progression of such quintessential expressions that begins with the zero-dimensional point. The one-dimensional line embodies extent in one dimension. The square embodies extent in two dimensions, the cube in three, the tesseract in four, and so on to higher dimensions. [See this post for more.]

In all cases, they’re governed by a single parameter: the length of a side. That’s what makes them so quintessential. That lone parameter embodies the very notion of extent along a dimension.

The other simple shape is the circle (in two dimensions), sphere (in three), or 4+ dimensional hyperspheres. And these, too, are governed by a single parameter: the radius. But note that, starting from the zero-dimensional point, there really is no one-dimensional circular shape, no analog to the one-dimensional line. So, as simple as the circular shapes are, I don’t see them as quintessentially embodying the very notion of dimensional space.

Something cool about both is that the derivative of their area or volume turns out to be their circumference or surface area. [See this post for details.]

And, as mentioned in that recent post, both these simple shapes, when examined closely, force us to accept the irrational numbers.

Back in the day, it wasn’t hip to be square, but squares are actually pretty cool.

§

Minor pet peeve: People who start a paragraph with, “Actually, …” It’s something I try to never do.

Actually, I generally succeed.

§

Languages evolve, and English is a particularly dynamic language. Many other languages end up borrowing English neologisms. Contrast that with German, for instance, which is notorious for creating words by stringing existing ones together:

Betäubungsmittelverschreibungsverordnung

A 40-character word that means “narcotic prescription ordinance”. On the other hand, English lacks great and useful words such as Weltschmerz and Schadenfreude. [See this post about the former word.]

But my note here concerns the evolution of language through misuse. Recently, in a New Scientist article, an author wrote:

I would have struggled to point to it on a map, let alone name which ocean it is.

(Emphasis mine.) To me, that’s backwards. The “let alone” clause should name the more difficult or challenging notion compared to the one named in the first clause. Presumably, picking an ocean is easier than picking a specific island in that ocean. Try reading it the other way around:

I would have struggled to name which ocean it is, let alone point to it on a map.

Doesn’t that feel more sensible? Admittedly, one has to think about it a bit, but you’d like to think a writer for a science magazine would take more care. It’s a trivial thing, but I worry about what we lose when our language becomes less precise. The old argument is, “Well, you know what I meant, right?” And, indeed, yes, in this case, despite a jarring sense of dislocation, the meaning is clear.

But sometimes it may not be. Communication, like the tango, takes two.

§

And yet, bear with me for a story from long ago (mid-1980s, I believe):

I had one of those minor life-changing moments where you suddenly see the world from another viewpoint and realize there’s a completely valid way of looking of things that had never occurred to you.

I was at a large family holiday gathering; the sort where you meet relatives you didn’t know you had or, as in this case, meet new spouses (of relatives I’d forgotten I had).

The spouse in question was a professional linguist. “Ah, ha!” I thought sub-consciously. “Here’s a chance for some professional validation on a point that’s been bothering me, but which seems to escape or not bother others.”

So I popped the question, “[As a professional linguist] Doesn’t it bother you how the language has devolved?”

The surprise answer was that, no it didn’t, because professional linguists study the language as it evolves, and linguistic evolution is neither “good” nor “bad”, it simply is (in dynamic languages).

I was left unvalidated but a bit wiser.

But I still regret the devolution of language. Useful terminology becomes diluted through misuse. Speech seems to be more and more context-dependent, iconic, and downright sloppy. (And by “iconic” I refer to desktop or app icons, those simplified pictograms that stand for something more complex. I’ve been complaining for a decade now about how iconic and lazy our storytelling is.)

§

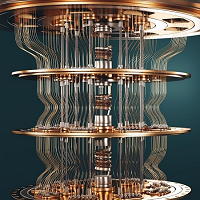

It blows my mind, so I have to share this chart (of local temps in February) again:

The highs range from +18° to +65° with an average high of +42.6°. The lows range from +4° to +39° with an average low of +24.6. Not a minus sign in sight! All of which is unheard of.

We had seven days with a high in the 40s and ten days with a high in the 50s (and one with a high +65°). There were only six days with a low below +20° and six with a low in the 30s (and 17 with a low in the 20s).

Mind blown (although maybe melted is a better word under the circumstances)!

§

Life is shit and chocolate. This applies to everyone and everything.

I suspect it’s like those optical illusions that are two pictures in one, but you can only see one or the other (for example, the faces/vase and the rabbit/duck illusions).

We simply can’t see both at the same time; we see one or the other depending on how we look at it.

Last night, watching an episode of Northern Exposure (a great TV series from the 1990s), I heard a fitting story told by the character Marilyn Whirlwind (Elaine Miles). As best as I can retell it:

There was a Chief who owned a fine horse. Everyone said how lucky he was. The Chief said, “Maybe.” Then the horse ran away. Everyone said he was unlucky. The Chief say, “Maybe.” Later, the horse returned with a fine string of ponies. Everyone said how lucky he was. The Chief said, “Maybe.” The Chief’s son was riding one of the ponies when he fell and broke his leg. Everyone said how unlucky this was. The Chief said, “Maybe.” Later the Chief led a raid against an enemy tribe, and many fine young men were killed. But the Chief’s son, because of his broken leg, stayed home and lived.

Yin-Yang, lucky-unlucky, faces-vase, it’s all in how you look at it. And sometimes, if you wait, things change.

§

A very old note due to a 2012 article in The Daily Beast, Consumption Makes Us Sad? Science Says We Can Be Happy With Less:

It may seem as though “how much is enough” is a very individual question. But it turns out that psychology has a good deal to offer us in the way of an answer. Psychology has developed a pretty rich understanding of what it is that produces happiness—what is sometimes called life satisfaction or subjective well being. And for the most part, what produces happiness isn’t stuff. People thrive when they have a network of close relations to others and when they have meaningful work that they find engaging. Stuff just doesn’t do it. And one major reason stuff doesn’t do it is a pervasive phenomenon known as hedonic adaptation.

Hedonic adaptation is just a fancy label for what we already know: we get used to things. The new car gets us all excited—for a while. But before long, it’s just our ride. The new tablet or smartphone is so enticing that we can’t keep our hands off it. But before long, it’s just another way for people we don’t want to hear from to lay responsibilities on us. There’s no denying that we get tremendous pleasure from the things we have. But the pleasure is disappointingly short-lived. And although this adaptation happens to us again and again, we never seem to learn to anticipate it. The result is that even when we get exactly what we want, we often end up disappointed.

This ties in with other studies I’ve read about that suggest that too many choices in life can also be source of discontent. Have you ever gotten stuck (like Buridan’s Ass) trying to pick what to watch amid the vast array of possibilities? It’s interesting that our rich and varied lifestyle may actually be a source of life dissatisfaction.

So, food for thought, if you ever find yourself wondering what’s missing in life. Maybe it’s not what’s missing so much as all the stuff that’s already there.

This also ties in with yesterday’s post about our obsession with growth. Simply put, humanity has become a victim of its own success.

§

As long as I’m quoting old texts, here’s another I found worth saving. It’s from The Trouble with Physics (2006), by one of my favorite theoretical physicists, Lee Smolin:

Science is one of several instruments of human culture that arose in response to the situation we humans have found ourselves in since prehistoric times: We, who can dream of infinite time and space, of the infinitely beautiful and the infinitely good, find ourselves embedded in several worlds: the physical world, the social world, the imaginative world, and the spiritual world.

It’s a condition of being human that we have long sought to discover crafts that give us power over these diverse worlds. These crafts are now called science, politics, art and religion. Now, as in our earliest days, they give us power over our lives and form the basis of our hopes.

Nice sentiment! One reason I like Smolin is his embrace of philosophy in science, something that many scientists sorely lack. The book is, as the title suggests, an examination of where physics seems to have run off the rails (or jumped the shark, if you prefer).

I agree and have written many times here about fantasy and science fiction in science. [See, for instance, Fairy Tale Physics, Our BS Culture, and Our Fertile Imagination for just a few examples.]

As an aside, theoretical physicist Peter Woit, the same year, wrote Not Even Wrong, which is a similar analysis that focuses on the foolishness known as String Theory.

§

For Christmas, and as a reward for all the Bentley-sitting I do (which, believe me, is its own reward, so this was gravy), BentleyMom gifted me with a set of four copper mugs for Moscow Mules. If you like mixed drinks and have never had a Moscow Mule, I highly recommend you try one. They’re currently my favorite mixed drink.

I discovered them several years ago while sitting in a bar with my bro-in-law. There was a row of shiny copper mugs on a shelf behind the bar, and I asked what they were for. The bartender replied they were for Moscow Mules. Never heard of them, says I, what’s in them? She listed the ingredients, which sounded delicious, so I ordered one.

And it was just as delicious as it sounded. Here’s a recipe:

- 1.5 ounces of vodka

- 0.5 ounces of lime juice

- 4.0 ounces of ginger beer

- 0.5 ounces of limoncello (optional)

- ice cubes

- lime wedge for garnish

- mint leaves for garnish

Ginger beer comes in 12-ounce cans, and I recommend using an entire can, so triple the first two ingredients to 4.5 ounces of vodka and 1.5 ounces of lime juice (and an ounce of the limoncello). The tripled recipe, along with the ice, fills two of the copper mugs to the brim.

Those copper mugs are said to add to the taste, the interaction between the ingredients and the copper. (One of these days I’ll try one in a glass to see if it tastes different.) Some have expressed concern about the potential for copper poisoning, but others feel the cold temperature and short durations involved remove any problem.

But none for Bentley! She has a hard time holding the mug in her paws.

§ §

Speaking of mixed drinks, I celebrated an expensive week with a couple (okay, three) caramel appletinis last night. Sour apple flavored vodka and butterscotch schnapps in roughly equal amounts, but more vodka and less schnapps unless you like them really sweet and butterscotch-y.

I would have preferred a Mule, but I’ve had that flavored vodka and schnapps in my fridge since around 2003. Decided I’d use them up despite not being particularly into appletinis anymore (my ex-wife and I were—discovered them in the bar of the 50s Prime Time Café at MGM Studios at Disneyworld—one of the few places you can get drinks there).

The week was expensive because Tuesday I did my taxes and owed the Feds again (but got some back from the state). On Wednesday I took my car in for service (and got a rental while they worked on it), and that ended up being over $2,400 all told. Ouch!

But it’s two huge items off my TODO list, and that feels pretty good!

Stay linguistic, my friends! Go forth and spread beauty and light.

∇

March 1st, 2024 at 7:37 pm

Actually… 😉

Linguistics is an interesting field. I gathered from watching John McWhorter on the Great Courses that linguists are constantly asked about why the English language is going down the tubes, but they don’t see it that way. McWhorter talks about how English has become grammatically streamlined over time because it’s one of the high contact languages that gets influenced by other cultures, their languages, and people who learn it as a second language. So while our vocabulary is immense, the grammar gets whittled down over long periods of time. Whereas a fairly insulated language like Navajo is left to evolve without those outside influences and it ends up being mind-bogglingly complex.

March 3rd, 2024 at 9:13 am

Ah, that makes a lot more sense than the usual canned answer that linguists, like anthropologists, are just observers who make no value judgement.

I hadn’t really thought about this until I pulled that bit out of an old notes file for the post, but I think what most mean (or at least what I mean) by the decay of language is the content rather than its structure, and I’m not sure linguists really address content. From what little exposure I’ve had to them, they seem to be entirely about structure. And, I would guess, how that structure is used by people — the various deviations from the current standard whatever that is.

I’m more focused on content — what people are saying (regardless of how they use grammar — that long-ago conversation with that relative stuck with me as far as language structure). I’ve pondered, if I could figure out how, doing an analysis of content of, say, the last two centuries (or even just one). Word vocabulary would be an easy metric, but I’d like to come up with some sort of content metric, something that considers our conceptual vocabulary. And that’s where I get stuck.

It feels as if we’ve become more simplistic but that could be my bias, my cynicism, my disdain for modern culture, so I need an “objective” metric. (That is to say, one that removes any bias on my part. 😉)

March 3rd, 2024 at 5:33 pm

I think to the extent that content can’t be separated from structure, linguists have to pay attention, but they don’t focus on it. They’re looking at languages from a long and far away view of things that most of us don’t know about. It very interesting stuff. I think they like to say they make no value judgements in the sense that they don’t think it’s important to “preserve the English language” and stuff like that. Where we see some sort of deficiency, they just see change as normal. What they like to look at is patterns of change, the way certain vowels have a tendency to drop off at the ends of words, and some look for universal grammar a la Chomsky (and that’s the stuff that will make your eyes cross).

I’m not sure vocabulary would be a good metric, actually. Having a small vocabulary doesn’t necessarily mean anything in terms of how you use language. I tend to think philosophers who avoid terminology explain things in a clearer way than those who like rely on the big words.

I think maybe the problem isn’t language, per se, but us. Maybe we have become too simplistic in our thinking. It could be that simple! 🙂

March 3rd, 2024 at 7:18 pm

Absolutely, and my interest is in how our speech, writing, and storytelling might reflect that!

Where a vocabulary analysis might make some sense is in an apples-to-apples comparison. For example, take a magazine that’s been published for at least 100 years and examine the articles over their span to see if vocabulary has reduced. As you said earlier, English total vocabulary is very large, but has our day-to-day working vocabulary become smaller? It’s a fair point that that may not track the richness of the content, but it at least would be an easier proposition than trying to analyze concept vocabulary. (On the other hand, it could also be a case of looking for your keys under the streetlamp because that’s where you can see.)

Something I’ve noticed reading some of the British mysteries (Agatha Christie, et many aliae) is the expectation that the reader is familiar with the works of Shakespeare and with Greek mythology — things that were once part of a good British education. There are also Latin and French phrases thrown around quite a bit, and I suspect there was also some expectation readers would understand many of those.

But that’s a texture I don’t see much in modern popular writing. And, indeed, how many readers today are familiar with the classics? Yet, it could be the same kind of topical writing that we do see today, with current events and modern popular media uses as references.

March 3rd, 2024 at 8:59 pm

The problem with tracking vocabulary is that it’s generally acknowledged that meanings can be expressed equally by languages with much smaller vocabularies. Consider the French “connaitre” (to be acquainted with) vs. “savoir” (to know). I’ve heard people claim that the French must think differently than we do because we don’t have that distinction in English, but of course we do, we just don’t have that distinction wrapped up in one word.

Other interesting things I learned about linguistics: We tend to think of grammar as being logical, but from a grand point of view, it just looks like a really a big hot stinking mess. Not logical. We tend to think gendered pronouns actually signify something about gender and shape the way we think—but meh, not really. Despite the millions of articles saying they do. (I guessed as much myself when I learned that the French word for vagina is masculine).

I imagine if you’re a linguist, the fact that we can communicate with each other must look like a miracle.

But yeah, I suspect the reason our writing doesn’t contain reference in Latin and Greek is because we’ve stopped caring about learning dead languages. That’s for the dead white guys. What could we possibly learn from them? 😉

I’d say what’s gone down the tubes is education in general. But maybe I’m wrong!

Here’s an old article, but you might find it interesting (I just skimmed it, and it seems similar enough to what I learned from McWhorter on the Great Courses):

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/aug/15/why-its-time-to-stop-worrying-about-the-decline-of-the-english-language

March 4th, 2024 at 9:07 am

Yes! Nail on the head. I’ve been ranting about the “Death of a Liberal Arts Education” since the 1970s! Exactly. Education has been watered down to the point some schools are largely holding pens for our young. (It just wrecks me that we don’t take teachers more seriously. It’s as if we don’t take the future seriously, which is weird and wrong to me.)

And I’ve long believed how we express ourselves reflects that. One place I notice it is in the sloppiness of more formal writing (magazine articles, for example). But as with most social observations, the observer has to try to overcome biases, and social observation is very tricky. I’ve never been able to come up with a decent metric, just vague notions of ‘concept complexity’ or ‘degree of nuance’.

The German words Weltschmerz and Schadenfreude are also examples of what you’re saying about vocabulary. We don’t have single words for those concepts, but we certainly don’t lack those concepts. Somewhere not long ago I read a bit about how we had our emotions, and some understanding of those emotions, long before we had words for them. The infamous example is the myth about how “Eskimos have 50 words for snow.” That wasn’t quite true to begin with (an anthropologist’s error that got perpetuated in the literature), but more to the point, even without living with snow constantly, we have many concepts of it: powdery snow, wet snow, drifting snow, blowing snow, yellow snow, slush, sleet, etc.

So, I agree a vocabulary comparison between languages only provides an exploration of the languages in question. Still, I think the apples-to-apples comparison I mentioned — say within the scope of a single magazine — might be interesting. Perhaps in just showing how vocabulary has evolved over time, even if it ultimately doesn’t say much about our culture.

Totally agree about grammar. I’m not sure anyone trying to learn English (or, for that matter, most modern languages) finds much logic in grammar. Languages evolve like coral, growing in every direction, and, as you said originally, English is notorious because of that high contact with so many other linguistic influences.

“I imagine if you’re a linguist, the fact that we can communicate with each other must look like a miracle.”

Ha! And, indeed, despite something like 10,000 years of practice, we still often fail to communicate!

March 3rd, 2024 at 7:19 pm

P.S. And, yeah, the idea of preserving the English language is a non-starter. That’s really what my relative cured me of!

March 2nd, 2024 at 7:02 pm

I love Bentley. I hope that my posts don’t start with “actually.” Cheers!

March 3rd, 2024 at 9:16 am

Ha, everyone loves Bentley, she’s utterly adorable!

I can’t recall any of your posts starting with “Actually.” It’s usually the beginning of a response to someone that one is about to school in something. It rankles because it’s a subtle snarky way to assert dominance.

March 3rd, 2024 at 9:19 am

Politeness would be to rephrase what someone is saying and then expressing yourself (actually) 🙂

March 3rd, 2024 at 9:58 am

Yes indeed! The feedback shows you heard and understood them (and ensures you did understand them). A lot of pointless arguments could be avoided if more people did this. In tense situations, it’s even wise to avoid words like “but” that directly contradict. Better to, as you say, just express yourself.

As an aside, another that rankles is “I don’t disagree with you.” Such a mealy-mouthed way of agreeing, usually when someone is forced to agree by facts or logic but secretly still doesn’t.

March 3rd, 2024 at 10:01 am

Hahahaha.

March 20th, 2024 at 2:43 pm

[…] The temps in February — traditionally our coldest month — were so bizarre that I made a chart to share [see Friday Notes (Feb 30, 2024)]. […]