Tag Archives: QM101

The previous post began an exploration of a key conundrum in quantum physics, the question of measurement and the deeper mystery of the divide between quantum and classical mechanics. This post continues the journey, so if you missed that post, you should go read it now.

The previous post began an exploration of a key conundrum in quantum physics, the question of measurement and the deeper mystery of the divide between quantum and classical mechanics. This post continues the journey, so if you missed that post, you should go read it now.

Last time, I introduced the notion that “measurement” of a quantum system causes “wavefunction collapse”. In this post I’ll dig more deeply into what that is and why it’s perceived as so disturbing to the theory.

Caveat lector: This post contains a tiny bit of simple geometry.

Continue reading

13 Comments | tags: measurement problem, QM101, quantum mechanics, quantum physics, Schrödinger Equation | posted in Opinion, Physics

Over the last handful of years, fueled by many dozens of books, lectures, videos, and papers, I’ve been pondering one of the biggest conundrums in quantum physics: What is measurement? It’s the keystone of an even deeper quantum mystery: Why is quantum mechanics so strangely different from classical mechanics?

Over the last handful of years, fueled by many dozens of books, lectures, videos, and papers, I’ve been pondering one of the biggest conundrums in quantum physics: What is measurement? It’s the keystone of an even deeper quantum mystery: Why is quantum mechanics so strangely different from classical mechanics?

I’ll say up front that I don’t have an answer. No one does. The greatest minds in science have chewed on the problem for almost 100 years, and all they’ve come up with are guesses — some of them pretty wild.

This post begins an exploration of the conundrum of measurement and the deeper mystery of quantum versus classical mechanics.

Continue reading

24 Comments | tags: measurement problem, QM101, quantum mechanics, quantum physics | posted in Opinion, Physics

Last time I explored the quantum spin of photons, which manifests as the polarization of light. (Note that all forms of light can be polarized. That includes radio waves, microwaves, IR, UV, x-rays, and gamma rays. Spin — polarization — is a fundamental property of photons.)

Last time I explored the quantum spin of photons, which manifests as the polarization of light. (Note that all forms of light can be polarized. That includes radio waves, microwaves, IR, UV, x-rays, and gamma rays. Spin — polarization — is a fundamental property of photons.)

I left off with some simple experiments that demonstrated the basic behavior of polarized light. They were simple enough to be done at home with pairs of sunglasses, yet they demonstrate the counter-intuitive nature of quantum mechanics.

Here I’ll dig more into those and other experiments.

Continue reading

10 Comments | tags: Bell's Theorem, photons, QM101, quantum mechanics | posted in Physics

Earlier in this QM-101 series I posted about quantum spin. That post looked at spin 1/2 particles, such as electrons (and silver atoms). This post looks at spin in photons, which are spin 1 particles. (Bell tests have used both spin types.) In photons, spin manifests as polarization.

Earlier in this QM-101 series I posted about quantum spin. That post looked at spin 1/2 particles, such as electrons (and silver atoms). This post looks at spin in photons, which are spin 1 particles. (Bell tests have used both spin types.) In photons, spin manifests as polarization.

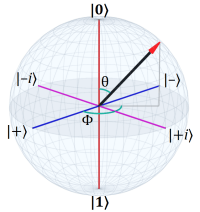

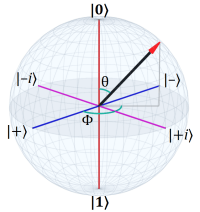

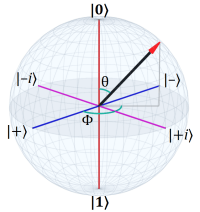

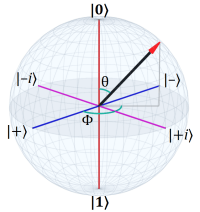

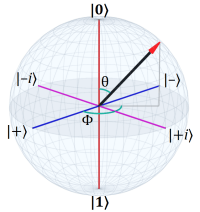

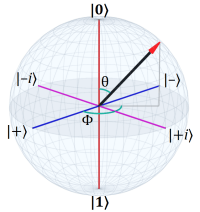

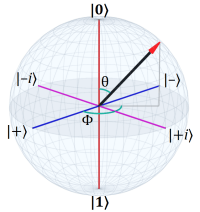

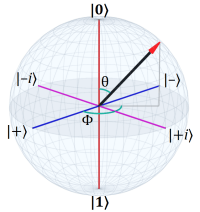

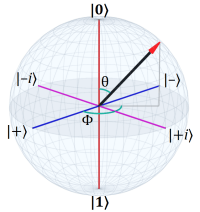

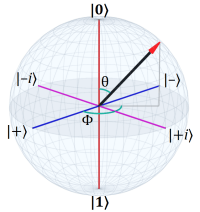

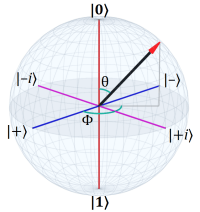

Photon spin connects the Bloch sphere to the Poincaré sphere — an optics version designed to represent different polarization states. Both involve a two-state system (a qubit) where system state is a superposition of two basis states.

Incidentally, photon polarization reflects light’s wave-particle duality.

Continue reading

8 Comments | tags: Bell's Theorem, photons, QM101, quantum spin, wave-function, wave-particle duality | posted in Physics

When I was in high school, bras were of great interest to me — mostly in regards to trying to remove them from my girlfriends. That was my errant youth and it slightly tickles my sense of the absurd that they’ve once again become a topic of interest, although in this case it’s a whole other kind of bra.

When I was in high school, bras were of great interest to me — mostly in regards to trying to remove them from my girlfriends. That was my errant youth and it slightly tickles my sense of the absurd that they’ve once again become a topic of interest, although in this case it’s a whole other kind of bra.

These days it’s all about Paul Dirac’s useful Bra-Ket notation, which is used throughout quantum mechanics. I’ve used it a bit in this series, and I thought it was high time to dig into the details.

Understanding them is one of the many important steps to climb.

Continue reading

14 Comments | tags: bra-ket notation, inner product, matrix multiplication, outer product, QM101, quantum mechanics | posted in Math, Physics

One small hill I had to climb involved the object I’ve been using as the header image in these posts. It’s called the Bloch sphere, and it depicts a two-level quantum system. It’s heavily used in quantum computing because qubits typically are two-level systems.

One small hill I had to climb involved the object I’ve been using as the header image in these posts. It’s called the Bloch sphere, and it depicts a two-level quantum system. It’s heavily used in quantum computing because qubits typically are two-level systems.

So is quantum spin, which I wrote about last time. The sphere idea dates back to 1892 when Henri Poincaré defined the Poincaré sphere to describe light polarization (which is the quantum spin of photons).

All in all, it’s a handy device for visualizing these quantum states.

Continue reading

16 Comments | tags: Bloch sphere, QM101, quantum computing, quantum mechanics, quantum spin | posted in Math, Physics

Popular treatments of quantum mechanics often treat quantum spin lightly. It reminds me of the weak force, which science writers often mention only in passing as ‘related to radioactive decay’ (true enough). There’s an implication it’s too complicated to explain.

Popular treatments of quantum mechanics often treat quantum spin lightly. It reminds me of the weak force, which science writers often mention only in passing as ‘related to radioactive decay’ (true enough). There’s an implication it’s too complicated to explain.

With quantum spin, the handwave is that it is ‘similar to classical angular momentum’ (similar to actual physical spinning objects), but different in mysterious quantum ways too complicated to explain.

Ironically, it’s one of the simpler quantum systems, mathematically.

Continue reading

40 Comments | tags: QM101, quantum mechanics, quantum spin | posted in Math, Physics

Unless one has a strong mathematical background, one new and perhaps puzzling concept in quantum mechanics is all the talk of eigenvalues and eigenvectors.

Unless one has a strong mathematical background, one new and perhaps puzzling concept in quantum mechanics is all the talk of eigenvalues and eigenvectors.

Making it even more confusing is that physicists tend to call eigenvectors eigenstates or eigenfunctions, and sometimes even refer to an eigenbasis.

So the obvious first question is, “What (or who) is an eigen?” (It turns out to be a what. In this case there was no famous physicist named Eigen.)

Continue reading

14 Comments | tags: eigenstate, eigenvalue, eigenvector, matrix transform, QM101, quantum mechanics | posted in Math, Physics

In quantum mechanics, one hears much talk about operators. The Wikipedia page for operators (a good page to know for those interested in QM) first has a section about operators in classical mechanics. The larger quantum section begins by saying: “The mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics (QM) is built upon the concept of an operator.”

In quantum mechanics, one hears much talk about operators. The Wikipedia page for operators (a good page to know for those interested in QM) first has a section about operators in classical mechanics. The larger quantum section begins by saying: “The mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics (QM) is built upon the concept of an operator.”

Operators represent the observables of a quantum system. All measurable properties are represented mathematically by an operator.

But they’re a bit difficult to explain with plain words.

Continue reading

6 Comments | tags: QM101, quantum mechanics, quantum operator | posted in Math, Physics

Last time I set the stage, the mathematical location for quantum mechanics, a complex vector space (Hilbert space) where the vectors represent quantum states. (A wave-function defines where the vector is in the space, but that’s a future topic.)

Last time I set the stage, the mathematical location for quantum mechanics, a complex vector space (Hilbert space) where the vectors represent quantum states. (A wave-function defines where the vector is in the space, but that’s a future topic.)

The next mile marker in the journey is the idea of a transformation of that space using operators. The topic is big enough to take two posts to cover in reasonable detail.

This first post introduces the idea of (linear) transformations.

Continue reading

13 Comments | tags: linear algebra, matrix transform, QM101, quantum mechanics, vector space, vectors | posted in Math, Physics

The previous post began an exploration of a key conundrum in quantum physics, the question of measurement and the deeper mystery of the divide between quantum and classical mechanics. This post continues the journey, so if you missed that post, you should go read it now.

The previous post began an exploration of a key conundrum in quantum physics, the question of measurement and the deeper mystery of the divide between quantum and classical mechanics. This post continues the journey, so if you missed that post, you should go read it now.