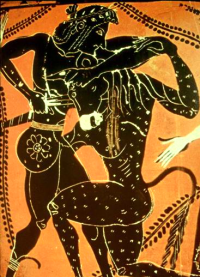

In Greek mythology, the hero Theseus, who slew the Minotaur and escaped its maze, returned from Crete to Athens where the Athenians preserved his ship in seaworthy state for more than a thousand years. It was an emblem of courage and a reminder of a national hero that many Greeks considered more legendary than mythological.

In Greek mythology, the hero Theseus, who slew the Minotaur and escaped its maze, returned from Crete to Athens where the Athenians preserved his ship in seaworthy state for more than a thousand years. It was an emblem of courage and a reminder of a national hero that many Greeks considered more legendary than mythological.

The Ship of Theseus was carefully maintained. Parts that rotted away were replaced with exact replicas. And in a ship made almost entirely of wood, crude iron, rope, and sail, everything rots, so eventually everything gets replaced.

Which makes the identity of the ship an interesting question.

If none of the original parts remains — let’s say even the metal bits have corroded and been replaced — it’s hard to claim it’s the same ship that sailed from Crete to Athens.

To make this obvious, imagine that some point after its return, the entire ship is carted away, and an identical replica moved into its place. The maintenance just accomplishes the same thing piecemeal over a period of time.

The historical Ship of Theseus… but is it really?

To make this interesting, imagine that one of the maintenance workers kept all the replaced parts and rebuilt the original ship in his backyard.

(Alternately, consider the original ship carted away to that backyard.)

When seen as two distinct ships that never touch, it seems clear that the original ship remains the actual historical artifact while the other represents, or stands in for, the original.

It’s less clear when the ship is replaced piece by piece, because when does the original become the copy?

At what point does the one in the backyard become the historical Ship of Theseus?

Does the order of part replacement matter? Is there a key part (the keel or the mainsail) that carries the ship’s identity? Does it matter if the parts are discarded or never assembled?

There is a modern variation on this; it’s often called My Grandfather’s Axe.

It’s been associated with both George Washington (of cherry tree chopping fame) and Abe Lincoln (of general axe chopping fame and, to some, vampire hunter whose preferred weapon was an axe).

It’s been associated with both George Washington (of cherry tree chopping fame) and Abe Lincoln (of general axe chopping fame and, to some, vampire hunter whose preferred weapon was an axe).

That version usually goes something like this:

My grandfather had a wonderful axe that he handed down to my father. At some point, my father had to replace the handle, which he did with an exact replica (same type of wood and everything). I inherited the axe, and recently I had to replace the axe blade (which I did with an exact replica).

Now nothing of the original axe remains. Is it really my grandfather’s axe? What I now hold in my hand has been “the family axe” since my grandfather bought it (and killed his first vampire with it).

If it’s a copy, did it become a copy when my father replaced the handle or when I replaced the blade? Is it the continuous role of Grandfather’s Axe that matters?

Not to be outdone, my favorite science fiction author, Terry Pratchett, tells the axe version in a Discworld story (The Fifth Elephant) that considers a sacred political object that is mysteriously stolen (from a locked room!) but later recovered.

Or is it? It appears the recovered object is a copy.

Or is it? It appears the recovered object is a copy.

And it turns out that the one that was stolen was also a copy.

Which makes perfect sense when you think about it.

Even very large scones, even of dwarf bread, do not last for centuries. Of course it’s a copy. Had to be.

But the role of the Scone of Stone, that never changes, the role endures!

Which brings us to the idea of continuity.

The Dwarf’s Scone of Stone, the Greek’s Ship of Theseus, the family axe, along with state roles like Presidents and Kings and Queens; these are continuous roles that are generally not fulfilled by the same continuous physical entity.

The old phrase, “The King is dead! Long live the King!” (which confused the crap outta me when I was young) speaks to how kingship transfers from person to person.

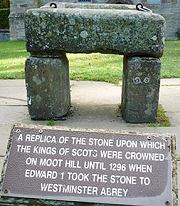

Scottish Stone of Scone

Terry Pratchett (I think in either Lords and Ladies or Carpe Jugulum) once said that kingship travels instantaneously — way faster than the speed of light!

(Which isn’t really a challenge on Discworld where light moves leisurely — even sluggishly in the morning.)

Here’s what makes all this interesting…

Physically, humans are replaced entirely every seven years or so. We have a new pancreas roughly every 24 hours. (This doesn’t happen all at once, obviously, but cell by cell — as if maintenance workers were replacing the rotted bits.)

This includes our brain cells, of course. Even the machinery of the mind is replaced.

Yet our minds seem continuous. Our patterns of consciousness do evolve and change over time, but we seem to have a continuous awareness. We have what is sometimes called a unitary experience.

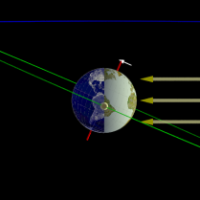

Recently the YouTube video below got me thinking about the supposed paradox of Theseus’s Ship, and while I don’t see much actual paradox in the physical example (it depends on original material versus defined role), it did generate some speculation about our minds.

(Which is really the whole point of the Ship of Theseus metaphor.)

For a moment, it occurred to me that the spark of continuous awareness might be evidence of something like a soul or, at least, an indication that the human mind is unique in interesting ways.

(Put that way, almost anything can be seen as interesting. If you can find something that’s truly not interesting, that is interesting.)

But imagine the following:

There is a computer designed to calculate the digits of pi. Which go on forever, so this computer cranks out pi digits until it finally dies of old age.

Calculates tons & tons of p!

In the meantime, it is maintained in good condition, and many parts can be (and are) replaced to keep it running. Even the algorithm that calculates the next digits can be patched to make it more efficient if a new method is found.

At some point vital parts can no longer be maintained, the machine dies, and the calculation stops.

If, as many believe, our minds are the result of a calculation, then this is a good analogue for what happens with humans. But (it is supposed) our minds don’t calculate pi; they calculate consciousness.

In the pi computer, even if it’s strictly a hard-wired computer, and even if it’s a mechanical calculator, we’re very clear on what comprises the algorithm and what comprises the matrix for the algorithm.

That’s the missing piece with software AI.

That’s the missing piece with software AI.

We have no idea how to separate the mind’s supposed “software” from the brain’s obvious hardware.

(Crucially: It may not be possible. Mind may supervene on the entire physical system. I am decidedly among those who believe mind is not an algorithm. See Information Processing.)

Either way, it’s interesting to think about the continuous «I» that each of us lives with. Just what is that core of personality who survives so intact all the years of our life as our body changes and ages?

Are we not, in so many ways, the same person we were as a kid, or in high school, or in college? And having learned and experienced, are we not, in so many ways, that same person?

How we change, what new things we take on board; and how we stay the same, what things we try to retain; these are a big part of what defines our character, nature, and personality.

So build and maintain your ships wisely! Use your grandfather’s axe.

March 20th, 2016 at 5:24 am

I’m not even convinced that consciousness is continuous. Sometimes when I wake up in the morning, I have to remind myself who I am and what I am supposed to be doing. There’s an idea that every time we go to sleep we die, and a near-identical copy of us rises the next day.

I think that what the Ship of Theseus really teaches us is that concepts like identity, that we can apply rigorously to mathematical objects, aren’t strictly valid when applied to physical objects, and we need to explain more precisely what we mean when we say that something is “the same.”

if anyone did ever manage to separate the mind’s software from the brain’s hardware, then the idea of “I” would be invalidated and we would have to rethink the whole concept from the bottom up.

March 20th, 2016 at 11:30 am

“Sometimes when I wake up in the morning, I have to remind myself who I am…”

Once the confusion lifts, do you believe your memories belong to anyone other than you? Are they your memories?

“There’s an idea that every time we go to sleep we die, and a near-identical copy of us rises the next day.”

Do you take that idea seriously? 🙂

“I think that what the Ship of Theseus really teaches us is that […] we need to explain more precisely what we mean when we say that something is ‘the same.'”

Agreed! (And very much a point of the post.)

“if anyone did ever manage to separate the mind’s software from the brain’s hardware, then the idea of ‘I’ would be invalidated and we would have to rethink the whole concept from the bottom up.”

Because?

Assuming software AI is possible (which I believe you do?), then the «I» is necessarily comprised of the brain’s HW and (assumed) SW. Further, under that assumption, some other combination of HW and SW must also produce that «I».

Why does that invalidate the idea of the «I»?

March 20th, 2016 at 1:08 pm

“Are they your memories?”

of course! But what that really means is the point of this post!

“Do you take that idea seriously?”

I would give it a 50% probability. But that doesn’t stop me going to sleep peacefully at night.

“Because?”

Because multiple copies of “me” might exist.

March 20th, 2016 at 1:55 pm

“But what that really means is the point of this post!”

So what do you think it means? (That they’re your memories and seem to indicate your continuous past.)

“I would give it a 50% probability.”

Do you really mean you think it’s just as possible as not that “every time we go to sleep we die, and a near-identical copy of us rises the next day.”

What about the way the brain stays very active during sleep? Brain wave change during sleep or unconsciousness, but they don’t go away. You clearly don’t mean “die” in the physical sense; the body remains alive during sleep, unconsciousness, even coma.

“Because multiple copies of ‘me’ might exist.”

Wouldn’t they all have the «I»?

There might be a conflation of two ideas here. The idea of continuity (which applies to your «I»’s sense of “me”) and the idea of the «I» (which applies to your phenomenological sense of experiencing reality).

To each of us they do appear the same, since our «I» seems continuous (although you seem to be disputing that).

If software AI permits multiple copies, each would have their own sense of the «I», but presuming AI software can be stopped, copied, or deleted, our sense of continuity needs to include branches and gaps.

Software AI puts things in Ship of Theseus territory — the purely physical. Analysis of the Ship shows that resolving the paradox is largely a matter of definition and provenance.

At that level, there really isn’t any paradox. I see it more, as you said, a thought-starter about identity as well as a thought-starter about how consciousness differs (or doesn’t) from physical objects. That’s also a kind of identity question, but with a side of human brain-mind problem thrown in.

(My kinda entree! XD )

March 21st, 2016 at 4:03 am

So I think that the human animal is a physical being with a non-physical mind that inhabits its own abstract space. Consciousness of that mind is interrupted to a greater or lesser extent by sleep, and so the “I” may be discontinuous in nature. If that separation is real (I’m not a sleep expert), then the “I” is a series of “I”s with temporal separations. Of course the “I” is discontinuous in many other ways too – there are two brains and many sub-brain units.

Plus, like you grandfather’s axe, the “I” changes very substantially over time.

“I think, therefore I am,” is therefore a very crude approximation of how the “I” really exists.

Now at present, even though it has a complex granular structure, the “I” is contained within a single physical body. If “uploading” could ever happen, then copies of the mind could be made. This would make the implicit problems about the “I” much more explicit and obvious. Even people who never think about what the “I” means would be forced to give it some thought. We would need to create new legal and ethical rules for how that worked.

As you say, there’s no paradox, unless we insist that shorthand ways of thinking about identity (my memories, my grandfather’s axe, etc) have some kind of deep truth.

As an aside, if it became possible to create multiple copies of the self, I would be first to sign up. Call me egotistical, if you like. 🙂

March 21st, 2016 at 10:54 am

“I think that the human animal is a physical being with a non-physical mind that inhabits its own abstract space.”

That sounds like a soul or something. 😀

What creates this non-physical abstract space? (Is it the same sort of space inhabited by an algorithm?)

“…the ‘I’ is a series of ‘I’s with temporal separations.”

We might be running afoul of two ways something can be continuous.

I mean it in the sense of continuous identity, not in the sense of an unbroken stream of consciousness (which would be impossible for human beings anyway).

I think we’re on the same page when we agree that the memories are our memories. They belong to the «Me» that’s been with us as long as we’ve been alive.

When philosophers talk about the “unity of experience” that’s what they’re usually talking about.

“Plus, like you grandfather’s axe, the ‘I’ changes very substantially over time.”

Really, it’s the «Me» that evolves. The «I» is just the experience of existing, the phenomenology of qualia, and that is fairly consistent throughout our lives.

“Now at present, even though it has a complex granular structure, the ‘I’ is contained within a single physical body.”

I think you’re still conflating the ideas of the «I» and the «Me».

If copies could be made, presumably each would have their own (self-contained) «I».

But your «Me» would branch to the copies where it would begin to diverge.

That said, software AI with uploaded minds would definitely take us into a close examination of both the «I» and the «Me». The former is the Holy Grail of AI. Both raise ethical and legal questions, but the latter does especially. (Do all my «Me»s have legal access to my stuff?)

“As an aside, if it became possible to create multiple copies of the self, I would be first to sign up.”

Heh. I’m quite confident that, if it’s even possible (and I don’t think it is), it’s way beyond our lifespans. It doesn’t seem to be a nut we’re close to cracking.

And I’m certain that uploading existing minds into software is the very last (and way least likely) thing we’ll accomplish. Every other goal of AI needs to be solved first.

Even if we gain the knowledge, the practical aspects may make it impractical. We’re talking petabytes, if not exabytes, of data.

March 21st, 2016 at 11:45 am

“Is it the same sort of space inhabited by an algorithm?”

Exactly so.

Me vs I? The first is an object, the second a subject. That’s all I know.

March 21st, 2016 at 1:36 pm

The thing about algorithms and math is that we see the connection between the abstraction and its physical instances. We can look at any physical computer (or physical manifestation of math) and see how the abstraction arises.

Currently not only do we have no clue about that wrt the mind, but we don’t even know if there is an algorithmic abstraction. (And, as you know, I say there isn’t.)

Not that this really has anything to do with the current post, and we’ve talked the AI aspects to death in the past, don’t you think?

“Me vs I? The first is an object, the second a subject. That’s all I know.”

The «I» is the experience of existing, the phenomenology of qualia. We all have a basically identical «I» (one assumes) in that everyone experiences phenomena.

The «Me» is your store of accumulated memories, experiences, and learning. Everyone has a different «Me».

March 21st, 2016 at 2:20 pm

Well I don’t know if there is an algorithm in the Turing sense, but there is information being moved about, and that’s what I’m talking about when I refer to a non-physical mind in an abstract space. That’s how I think of it.

March 22nd, 2016 at 12:13 am

“Well I don’t know if there is an algorithm in the Turing sense,”

(Sidebar question: Then have you become agnostic or skeptical regarding software AI? I ask because, in the past, you’ve asserted a positive belief in a computational theory of mind.)

“[T]here is information being moved about…”

Right.

I had to wind this back to figure out where this was supposed to be headed. It was about the abstraction of the human mind, and that was in regard to the continuity (or not) of our personal experience (our «Me»), and that was off your very first sentence in this thread:

“I’m not even convinced that consciousness is continuous.”

I think we agree the «I» experiences sleep (or unconsciousness or even coma) on a very different level than wakefulness. That you respond to external input (including being wakened) during sleep seems to indicate a “standby” state of sorts that is aware of external input.

There is even evidence that people experience something while anesthetized or in a coma, so our conscious mind may experience a discontinuity, but who’s to say our subconscious mind does?

Regardless of how continuous (or not) the «I» seems phenomenologically, the «Me» equally seems continuous (phenomenologically). Our blurry-eyed response upon waking not withstanding. XD

So given the nuance we’ve added during our discussion, how say you now?

March 22nd, 2016 at 3:00 pm

I haven’t changed my “mind” about the nature of the mind – I was just pushing that issue to one side so as not to get side-tracked. 🙂

When I wake up, sometimes I am alert and jump out of bed to pursue my day’s goals without hesitation. On other days (especially if I have a power recharge in the afternoon) I awake unaware of what time it is, what day it is, what my name is, and what I am supposed to be doing. I have to re-load those facts into RAM and spend some time booting up before my apps are ready to launch. 🙂

Once I fainted, and although I was unconscious for about 30 seconds, I experienced it as a split-second break in my awareness, and couldn’t understand how I had moved from a standing position to lying on the floor instantaneously.

I was once under general anaesthetic for several hours, and (unlike during sleep) when I woke I had no sensation that any time had passed. So I think the body’s “awareness clock” must stop during such periods of deep unconsciousness.

Those seem like real breaks in consciousness. I think that the brain is constantly experiencing temporal discontinuities of one kind or another, and that on the whole it is a rather flaky device that is basically duct-taped together to make it function adequately. Mine is, at least.

March 22nd, 2016 at 5:22 pm

Okay. Just to be sure I understand you: You feel there is no distinction between what our body (including our physical brain) experiences, what our full mind (including subconscious) experiences, and what our awake mind experiences? These temporal discontinuities occur on all three levels?

(As a side note: I’ve experienced a few forms of unconsciousness, including a general anesthetic. Which I have to say was awesome! XD Reality literally blinked from watching them do the injection to the nurse standing over me saying “That’s it, all done!” The only after effect was feeling very happy and a little bit float-y. 😎 )

March 23rd, 2016 at 4:14 am

No, the opposite!

March 23rd, 2016 at 9:35 am

I’m confused.

“Those seem like real breaks in consciousness.”

Do you mean consciousness in the awake sense (“I woke up after a nap.”) or conscious in the AI sense (“The conscious mind”)?

Obviously I completely agree with the former, but I’ve been leaning against the latter. I don’t know that the subconscious experiences discontinuities.

“I think that the brain is constantly experiencing temporal discontinuities of one kind or another…”

I’ve been disputing that. I’m not convinced the brain experiences any real discontinuity at all.

What distinction are you drawing between these three?

March 23rd, 2016 at 11:04 am

Well I can’t know what the subconscious experiences. perhaps enough of the mind continues that the whole thing can be regarded as a continuous whole. Who knows?

But I experience normal, waking consciousness as a rush of competing thoughts and sensations. Thoughts drift into focus for a while, then are replaced by others. It feels like lots of voices beckoning for attention, and I don’t think I’m insane. If you’ve every tried meditation, you’ll know how much noise and chaos goes on inside your head all the time. It’s almost impossible to think sometimes …

So I think the “I” is something of an illusion, in the specific sense that the brain/mind operates more like a community than a singular entity.

March 23rd, 2016 at 11:57 am

“Who knows?”

Scientists. XD

“I don’t think I’m insane.”

I’m pretty sure we would have noticed!

“So I think the ‘I’ is something of an illusion, in the specific sense that the brain/mind operates more like a community than a singular entity.”

I very much agreed the mind is legion! That doesn’t invalidate the «I», though.

The «I» is just the fact that you experience the world.

March 21st, 2016 at 4:04 am

So why do you use the English spelling of axe instead of the US ax?

March 21st, 2016 at 10:58 am

The distinction isn’t as sharp as for, say, color-colour or analyze-analyse (let alone hood-bonnet or trunk-boot 🙂 ). Both forms are used in the USA. (Wiktionary says some use the two forms to disambiguate between the weapon and the tool, but doesn’t say which is which!)

Plus, I like vowels and don’t want them to be lonely.

March 27th, 2016 at 1:18 pm

I love the Ship of Theseus paradox. And the fact that you squeezed in “Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Hunter.” (In a writing workshop I attended a few years back, there was a contest to see who could write the best terrible trendy title. I forget which one won, but there were some good ones. This was the example used to explain the contest.)

I tend to think that identity of objects is a little different from identity of self. The Ship of Theseus as a not-person-object is the easier one to deal with. The extreme POVs:

a) Materialist: The ship is nothing but it’s original parts, so once all of its parts are gone—or it’s reached a critical mass of loss, or some other materialist criterion—the ship is not the same. It’s another ship altogether.

b) Platonist: The ship is an idea, a design, regardless of what it’s made of. As such, it will always exist. Even if there are millions of replicas.

My thoughts: “The ship of Theseus” is both a and b. In this particular case, we’re dealing with an oft-used example of a tension between material reality and ideal reality. As a paradox, the ship of Theseus IS both, literally. There might be some way around this by talking about the ship of Theseus outside the paradox it’s usually intended to conjure up, but that’s rare.

Now you could talk about other ships, other artifacts, and say “this one’s original” and “this one’s not original” based on the material. That’s because we’re looking for historical meaning. Original vs. copy matters a great deal then. So if someone took an artifact and replaced it with newer parts bit by bit, they’d be destroying the artifact as an historical record…as, well, an artifact. Same goes for historical vehicles…people care a great deal about getting original parts when they restore a car, but I have no idea at which point the car becomes no longer historical. (Can I use a copy of that particular part, that one screw, for instance, or do I have to really get a screw that was from a particular time period? And does the screw count even then as “original”?) Here we have a continuum, probably based on how much we care about how accurately historical a thing is.

In other cases, like, say, the ordinary speed boat, we don’t really care about it’s parts or what it’s made of just so long as it continues to meet the criteria of “speed boat.” What we care about there is the function, the idea. Replacing the speed boat bit by bit doesn’t make it a different thing altogether. It’s still my speed boat that takes me across the water at fairly high speeds.

So all of the above sounds very subjective—you know I like that sort of thing—but I really do think it’s a matter of language. And a matter of language is not “just” a matter of language. The way we consider an object has a great deal to do with what it means, and even what it is in some cases.

On the self…I tend to go with Kant. If we want the self to be some consistent or persistent thing (not that it will live forever, but you know what I mean), the transcendental unity of apperception does the trick. Personality changes, my body certainly changes, etc. The feeling we have of a self can’t be explained away as an illusion, it must be dealt with directly…but what IS it? For epistemological reasons, I tend to think that something so pervasive in our experience can’t be dismissed so readily, yet the self doesn’t seem to me to be much more than this unity that you brought up. (Or we could be more specific and describe the unity, which might turn out to rely on other factors, etc., but let’s keep it simple for now.) It’s a unity that keeps me on this side of sane, for sure, but I can’t imagine experience without it. (A sort of Kantian way of thinking.) 🙂

But this is a very contentious subject, so I’ll play devil’s advocate:

You could argue that “unity” is nothing really, just an unreliable subjective experience. It’s not a self, just a part of our mental machinery. It’s a ghost in the machine, and ghosts don’t exist.

You could argue that the self isn’t unified, that we’re making that up. (Enter the subconscious, the unconscious, multiple personality disorders, or whatever here, if you like, or not.)

You could argue that unity is not what we mean by “self,” even if it does seem to accurately explain our experience. When we talk about the self, we’re talking about a person with personality traits, not some unity, some blank and utterly empty “I” that accompanies all my apperceptions. That’s just semantics. There might really be a unity of apperception, but that doesn’t address the question of self in any meaningful way. (I think this is the best argument.)

March 28th, 2016 at 9:32 am

“[P]eople care a great deal about getting original parts when they restore a car, but I have no idea at which point the car becomes no longer historical.”

Cars are one example I didn’t have room for in the piece, but which I thought might come up in discussion. As I understand it, when it comes to historical cars, the ideal is that any replacement parts were manufactured in the era of the car and for that car. This allows one to say the car is “as if” if was new in its own era.

Less ideal would be parts manufactured in the modern era, but for that car and per original specs. And it gets less and less ideal from there as one gets further and further from the idea of “original parts.” As you said, “a continuum.”

Obviously I agree completely about Materialist versus Platonist views. 🙂

It’s probably even easier with the axe, since it has just two parts. Other than fulfilling some family role as “Our Axe” it seems obvious it’s no longer really Grandfather’s Axe as soon as either the blade or handle is replaced.

A more precise use of language might have us saying, “The axe my grandfather bought (and which we’ve repaired many times).” Or just, “the family axe.” As you point out with your speedboat example, the function is generally the point when it comes to axes and boats and such.

As you also point out, it seems different when it comes to self and other person-objects. And you know how much I like Kant, so we’re aligned there, too.

“The feeling we have of a self can’t be explained away as an illusion, it must be dealt with directly…but what IS it?”

And the apparent qualitative difference between person-objects and not-person-objects seems to make this an interesting question.

Or is it simply that person-objects are so much more complex than the not-person-objects that it only looks like there is a huge difference.

“But this is a very contentious subject, so I’ll play devil’s advocate:”

Oh, oh! I’ll do my best against your philosophical might! XD

“It’s a ghost in the machine, and ghosts don’t exist.”

Even if the subjective experience is unreliable, it still exists, which seems to prove that ghosts of some sort do exist in this machine.

“You could argue that the self isn’t unified, that we’re making that up.”

All of us in such a universal fashion? I suppose it’s possible, and it’s actually an argument that atheists make (whether they realize it or not). The apprehensions of reality that so universally lead every culture towards religious ideas seems to indicate a perception of something true… or a global human tendency.

It raises the question: Why? What’s it for?

It turns out that primitive societies with “king gods” (who laid down moral and social law) could grow much larger than societies without one. I’ve long wondered if religion had an evolutionary value, and it seems it might.

Is there an evolutionary value to phenomenal experience that tricks us all into thinking a unified identity lives in our head?

“You could argue that unity is not what we mean by ‘self,’ even if it does seem to accurately explain our experience.”

What about when the personality becomes drastically altered (say through Alzheimer’s)? Those who love someone who has become altered that much love the person (the unity?) they knew. I suppose there’s a fine line between a collection of acquired personality traits and the unity that supposedly underlies them.

We certainly assume some sort of unity when dealing with others. We expect them to remember previous conversations, for instance.

In the discussion with Steve, we found it necessary to distinguish between the «I» and the «Me». The former is the moment-to-moment experience of experiencing; the latter is that acquired set of traits and experiences.

I agree very much that the «I» isn’t what we mean when we think of others. We think about their «Me». (Really, a big problem for AI and philosophy here is that the «I» of anyone else isn’t accessible except through personal testimony. We’re all assuming we’re all experiencing the «I» in a similar fashion.)

“There might really be a unity of apperception, but that doesn’t address the question of self in any meaningful way.”

I agree. It doesn’t address it, but it does make it interesting! XD

January 5th, 2021 at 10:10 am

[…] My Grandfather’s Axe has turned to be a popular post, too, which makes me happy. I’m kinda proud of that one (it’s #2 this year and #2 overall). […]

July 4th, 2021 at 2:13 pm

[…] My Grandfather’s Axe (5071/903) […]

November 15th, 2022 at 6:55 am

What excellent writing! 👏👏👏

November 15th, 2022 at 7:50 am

Welcome new visitor, and thank you for your kind words!

January 14th, 2023 at 3:08 pm

[…] My Grandfather’s Axe (2016, 6031) […]

January 19th, 2023 at 7:25 am

1) “they calculate consciousness.”

2) “what is that core of personality ”

3) “Are we not, in so many ways, the same person we were as a kid”

4) “what defines our character, nature, and personality.”

Hmmm, well, I do address all those curiosities in my book, “Election 2016”; but very briefly:

1) I think that might be backwards. Consciousness is because of the ability to calculate. (see selfawarepatterns latest post).

3) Yes. “The child is father to the man” (Wordsworth, 1802. Predates Freud.)

2 & 4) I’m with you here. I submit that character, personality, soul & nature, are similar enough to be the same thing. Personality being our “personal reality” which remains the same once fully formed (at around 22 years). It is Forged in the formative years. To change the core of Self (one’s personality) is really hard work – the stuff of psychoanalysis. I’ve been working on it with psych-girl for over 5 years now. We’ve come to an understanding … 🙂

~ then there is “The soul of man”. Great song by Bruce Cockburn.

January 19th, 2023 at 12:07 pm

1) Keep in mind, under computationalism, there are two uses of “calculate” here: Firstly, the belief the brain is a computer, and what it computes (calculates) is human consciousness. Secondly, because of consciousness (however it arises), we can do half-assed math (calculate). We’re usually not very good at it. Mike (SelfAwarePatterns) and I debated this for something like eight years, so I’m quite familar with his take on it.

2) Just an aside that here I meant the sum total of our entire history to “now” (whenever “now” happens to be). In this case, what happened yesterday, last week, or last year, can have more weight than what happened in our youth.

3) Totally (and good quote). However, the next sentence asks (in what I later realized was extraordinarily bad phrasing) if it isn’t true that we’re not the same, that we do evolve over time. And I think we do. Much of my core comes from my formative years (my “Wonder Bread years” — not many get that reference anymore), but that core has evolved over time. I am definitely not who I was in my teens or twenties. I’m not even who I was in my forties!

4) I would argue there are shades of meaning between those, but I take your meaning. And I definitely agree with your general premise that our core values and worldviews are formed early and tend to persist. But, exactly as you say, we can (and should!) work on ourselves. (I’ve been doing that since my 20s which is exactly why I have changed. I don’t have to tell you: it’s a process!)

Bruce Cockburn? A favorite artist, a beloved album, and faithful cover! It was written by the great Blind Willie Johnson.

January 19th, 2023 at 12:08 pm

For comparison:

It even kinda has that old time-y sound!

January 19th, 2023 at 3:32 pm

errg ” Keep in mind, under computationalism, there are two uses of “calculate” here:”

I am not sure what that means. I’m a psych-guy. Keep that in mind? I.e. the unseen, the unconscious.

January 19th, 2023 at 4:02 pm

Perhaps I’ve misunderstood. You called out my phrase “they calculate consciousness” and commented:

“I think that might be backwards. Consciousness is because of the ability to calculate. (see selfawarepatterns latest post).”

I’m not sure what you’re referring to in Mike’s post, but I took you to mean that our human consciousness is what allows us to “calculate” (do math, figure stuff out, etc). Which is true, but not what I was talking in the post.

Under computationalism (which Mike accepts and I’m skeptical about) the brain (“hardware”) is viewed as a computer running “software” — the mind. By “calculate” I was referring to the putative computation done by the brain computer, not what our minds can “calculate”.

That help any?

January 19th, 2023 at 4:47 pm

Somewhat? I’m well into my whiskey brain now so … . I wish we could all gather ’round a campfire and converse. Psych-girl? she’d be taking notes. and laugh/smirk/nod – men. Yep. and up her fee.

January 19th, 2023 at 6:46 pm

Think of it as the difference between the CPU calculations your computer makes to run the calculator app versus the math calculations the calculator app does when you use it.

August 15th, 2023 at 3:11 pm

[…] My Grandfather’s Axe (6,169): For a while I thought this post would be more of a contender for first place, but it lags behind by over 2,000 hits, so obviously not. On the other hand, it’s nearly 2000 hits ahead of the third-place post (below). Lately, interest seems to have dropped off rather severely, but it remains one of my favorite posts. One I’m proud of. […]

September 5th, 2023 at 5:59 pm

[…] My Grandfather’s Axe (3591) […]

September 5th, 2023 at 6:11 pm

[…] My Grandfather’s Axe (March 2016; 1017) This one, about identity, seems increasingly popular. It had only 61 hits in 2016, but 369 the year following, and 587 already this year. […]

January 17th, 2024 at 4:00 pm

[…] a while, I thought My Grandfather’s Axe was going to become my #1 post, but views tapered off considerably in the previous two […]