It’s been a while, but the two previous posts in this series (this one and this one) explored the mechanism behind partial differential equations that equate the time derivative (the rate of change), with the second spatial derivative (the field curvature). The result pulls exceptions to the average back to the average in proportion to how exceptional they are.

It’s been a while, but the two previous posts in this series (this one and this one) explored the mechanism behind partial differential equations that equate the time derivative (the rate of change), with the second spatial derivative (the field curvature). The result pulls exceptions to the average back to the average in proportion to how exceptional they are.

Such equalities appear in many classical physics equations where they have clear physical meaning. Heat diffusion (explored in the previous posts) is a good example.

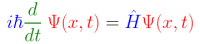

In quantum mechanics, they also appear in the Schrödinger Equation.

I’ll say upfront no one really knows what the physical meaning of this one is, but here we’re going to take a (shallow) look at its mathematical meaning. I’ll come back to the issue of physical meaning another time.

Here’s one way (of many) to write the Schrödinger Equation:

This is a time-dependent version for a case with only one physical dimension — movement along the x axis. I’ll expand on that below, but first a quick introduction of the cast. From left to right:

Blue: the imaginary unit, i, and the ubiquitous quantum constant, h-bar (h). Both contribute to the quantum nature of the equation. The first means quantum calculations necessarily use complex numbers. The number i often appears in classical physics, but usually just as a convenience for easier calculation. In quantum math, complex numbers seem required. The constant, h-bar (the reduced Planck constant h÷2π), provides both the quantization constant and the units needed to balance the equation.

Green: d/dt, an operator that returns the first derivative of time. This is an operator, so it applies to the term that comes after it (the wavefunction) and gives us the time derivative (the rate of change with respect to time) of that term. [See QM 101: What’s an Operator? for more on operators.]

Red: (capital) Greek letter Psi (Ψ), the quantum wavefunction for the system in question. This is one of the key pieces of the equation, and it appears on both sides of the equality. Note that it takes two parameters, x and t. The latter tells us this form of the Schrödinger Equation is time-dependent (time is a parameter). The former is the single dimension of movement. (A version for three-dimensional space requires x, y, and z.)

Equals sign: The above terms must give the same value as the terms below.

Blue: H-hat, the quantum Hamiltonian operator for the system in question. This is the other key piece of the equation, and, as with the wavefunction, it must be constructed specifically for the system in question. H-hat is an operator (signified by the hat), so it acts on the term that follows it (the wavefunction).

Red: Psi, again, the quantum wavefunction, same as above. As with the Hamiltonian, Psi must be constructed for the specific system in question. Because this formulation of quantum mechanics is a wave mechanics, Psi typically consists of a set of sine waves of different frequencies and amplitudes.

[In the same way that any sound is a combination of sine waves, a quantum wavefunction for a given system is a combination of sine waves (in complex space). But unlike sound, no one knows the physical meaning of these waves. They seem to be waves of probability, whatever that might mean.]

In summary, there is the wavefunction, which appears on both sides of an equality, and on each side, it’s operated on by an operator. On the left side, the operator returns the time derivative — how fast Psi is changing at moment t. On the right side, Psi is operated on by the Hamiltonian, which embodies the energy and mass of the system. As we’ll see below, the Hamiltonian includes a second derivative of space, which tells us how fast the wavefunction is changing along the X-axis.

§

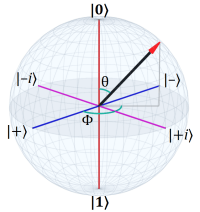

The quantum wavefunction, Ψ(x,t), embodies the quantum state. We typically visualize it as a vector moving in Hilbert space under the influence of the wavefunction. Given a position, x, and a time, t, the wavefunction returns a probability density. (The square of which gives the actual probability of finding the particle at that location at that time, should we look for it.)

There’s a lot to dig into with wavefunctions, but for now it’s enough that the wavefunction is a mathematical function that takes inputs and returns a value. Different systems require different wavefunctions. In the simple one-dimensional cases used for illustration, the wavefunction has an x parameter (position) and a t parameter (time). The value it returns therefore depends on both position and time.

Note that a wavefunction returns a value for all positions and all times. The quantum state evolves smoothly and completely predictably as determined by the wavefunction. This is why quantum mechanics — with a critical exception — is considered fully deterministic. But the exception, when two systems interact causing apparently random “collapse” of the wavefunction, is a central aspect of the “weirdness” of quantum mechanics. As with the physical meaning of the wavefunction, no one yet understands wavefunction collapse. [See these posts for more on collapse.]

The wavefunction appearing on both sides is an important part of how these equations work. For example, the heat diffusion equation had the heat function on both sides of the equals sign. The left side takes the time derivative while the right side takes the second derivative of the position. In this sense, such equations are a bit like eigenfunction equations:

Where the vector |ψ〉 appears on both sides of the equality. On the left, it’s acted on by O-hat (an operator of some kind that acts on the vector). On the right, it’s acted on by the eigenvalue lambda (λ), which only scales the vector. For the equality to be true, the action of the operator on the left must also only scale the vector — so the vector has to be an eigenvector. [See QM 101: Eigen Whats? for more on eigenvectors.]

Along those lines, there is a version of the Schrödinger equation that looks like this:

The Hamiltonian operator is on the left now (because, as above, the eigen equation usually has the operator on the left). On the right, the energy eigenvalue, E, also acts on Ψ but can only scale it (not move it). That means the Hamiltonian must also only scale Ψ for the equation to work.

§

The other major player in the equation is that blue capital H with the circumflex (called a hat, so the variable is called H-hat). This is the quantum Hamiltonian defining the potential and kinetic energy environment of the wavefunction.

Its exact mathematics depend on the system in question. For our simple one-dimensional example, we can define it like this:

The blue brackets replace the H-hat variable. Note that it is divided into left and right parts by the plus sign. The left part describes the kinetic energy of the particle. Note the mass of the particle, m, appears in this part. And the quantizer, h-bar, also appears.

The function V(x,t) defines the potential energy due to the environment. If the particle is moving through free space and not under the influence of external forces (the simplest possible case), this term vanishes.

Most importantly, on the left side of the Hamiltonian we see the second (partial) spatial derivative: ∂²/∂x². Recall that this describes the curvature of the wavefunction at x.

Because the Schrödinger Equation is an equality, the value on the left of the equal sign must match the value on the right. As with the diffusion equation, the left value reflects the rate of change (in a given spot) over time while the right value reflects the curvature of the wavefunction (in a given spot at a given time).

[BTW: This requires solving a partial differential equation, which can be difficult, especially for more complicated Hamiltonians. Basically, one has to find the right wavefunction to make the equality true.]

§

And lastly, a few more words about the blue ih on the very left of the Schrödinger Equation. I mentioned that h-bar provides the necessary units to balance the equation. The Planck constant is 6.626×10⁻³⁴ joule per cycle (J·Hz⁻¹). The reduced version, h÷2p, is 1.05 ×10⁻³⁴ joule per second (J·s⁻¹).

So, the units provided are joule per second (the joule is a unit of energy). Note that h-bar also appears in the Hamiltonian, providing the units for the right side.

The imaginary unit, as mentioned, places the math in the complex domain, and this seems unavoidable in the quantum realm. Nature, at this level, seems to use complex math (and no one is quite sure what that means physically).

There are some notable points, though. Complex numbers allow a wavefunction to interfere with itself (which we see happening in two-slit demonstrations). They also make oscillation a natural feature, which is a natural fit for a wave mechanics. One place they appear often in classical physics is in calculations for the wave mechanics of optics or radio.

The imaginary unit turns up again in definitions of the wavefunction, where, again, it’s involved in oscillation — the production of waves. Here’s an example of a very simple wavefunction:

This generates a single-frequency wave and might represent a particle with a well-known momentum state. Note how the parameters x and t appear in the exponent of the exponential. The k variable is the wave number — it controls the frequency of the wave. The omega (ω) variable controls the phase of the wave.

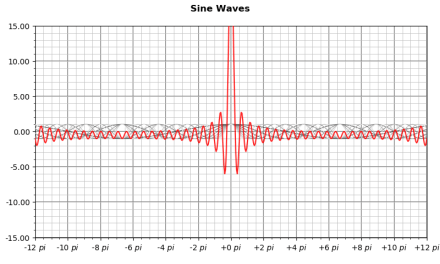

This is the simplest possible example of a wavefunction. Most definitions involve a series of sine waves with different frequencies and amplitudes. For instance, a position wavefunction is wave packet of many waves whose sum creates a single most-likely location for the particle:

The contributing sine waves are shown in light grey. The red curve — representing the most probable location of the particle — is their sum.

§ §

One last note: the Schrödinger Equation is not relativistic. In calculations with it, inertial observers moving at different speeds will see different waves and thus assign different energies or momentums to particles. The Schrödinger Equation is only useful in contexts where that doesn’t matter.

There are relativistic equations for quantum mechanics, but they are most definitely topics for another time. (They’re still ahead of me on my journey, so I’m hardly ready to post about them!)

Note also that things get a lot more complicated when, as we must for real-world calculations, include a particle’s spin and other quantum properties. Most uses of the Schrödinger Equation involve only a particle’s momentum versus position, so that’s all the information the wavefunction must embody. Other properties make it more complicated.

Fundamentally, that quantum mechanics is a wave mechanics traces back to the notion Louis de Broglie startled us with in 1924, that all matter — not just light — is wave-like (experimentally proved in 1927).

So, it really does make sense to represent particles as a set of sine waves.

Stay waving, my friends! Go forth and spread beauty and light.

∇

September 20th, 2023 at 2:46 pm

When reality waves, wave back!

September 20th, 2023 at 2:53 pm

I do sometimes feel that, despite being a wave mechanics, QM doesn’t take the de Broglie matter wave aspect of reality seriously enough. Seems as if many of the supposed weirdness might go away if we did. Superposition and interference certainly don’t seem as mysterious with matter waves — more the expected behavior.

Einstein’s spookiness remains, though. So does the apparent non-locality of entanglement (which was not what Einstein meant by spooky action at a distance — he was referring to the instantaneous vanishing of the wavefunction upon collapse).

September 20th, 2023 at 4:42 pm

This is way beyond my limited mind could comprehend. I got a headache no, wher’s my asprines.

September 20th, 2023 at 4:49 pm

Ha, I don’t blame you! I’m writing this QM-101 series for people like me who have an avid interest in quantum mechanics but were never schooled in, just read whatever pop-science books about it they could. A few years ago, I started trying to learn the mathematics, and much of it is beyond me, too, but what I’ve managed to pick up has been fun, so I’m spreading it around for others who are trying to jump that gap.

September 20th, 2023 at 4:43 pm

2 spelling mistakes. How did that happened.

September 20th, 2023 at 4:50 pm

If you were using your phone, it’s no surprise. Such tiny keys. I’m amazed every time I manage to pull off a chat on my phone. I’ll take a full keyboard any day (and I still end up doing a lot of backspacing).