Flat Earth!

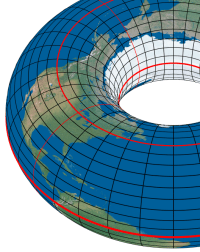

To describe how space could be flat, finite, and yet unbounded, science writers sometimes use an analogy involving the surface of a torus (the mathematical abstraction of the doughnut shape). Such a surface has no boundary — no edge. And despite being embedded in three-dimensional space, the torus surface, if seen in terms of compensating surface metric, is indeed flat.

Yet a natural issue people have is that the three-dimensional embedding is clearly curved, not flat. It’s easy to see how wrapping a flat 2D sheet into a cylinder doesn’t distort it, but hard to see why wrapping a cylinder around a torus doesn’t stretch the outside and compress the inside.

In fact it does, but there are ways to eat our cake (doughnut).

Last week I introduced you to the idea of relative motion between frames of reference. We’ve explored this form of relativity scientifically since Galileo, and it bears his name: Galilean Relativity (or Invariance). Moving objects within a (relatively) moving frame move differently according to those outside that frame.

Last week I introduced you to the idea of relative motion between frames of reference. We’ve explored this form of relativity scientifically since Galileo, and it bears his name: Galilean Relativity (or Invariance). Moving objects within a (relatively) moving frame move differently according to those outside that frame.