Consider the lowly square, a four-sided shape with sides of equal length meeting at right angles. The embodiment of what we’re referring to when we refer to square miles, square kilometers, square inches, or square whatevers. The two-dimensional version of any one-dimensional length.

Consider the lowly square, a four-sided shape with sides of equal length meeting at right angles. The embodiment of what we’re referring to when we refer to square miles, square kilometers, square inches, or square whatevers. The two-dimensional version of any one-dimensional length.

A trivially easy shape to draw, all you need is a straight edge and a compass — the latter for ensuring your corners are right angles (see Plato’s Divided Line for more on using a straight edge and compass). The only simpler shape is the circle.

Yet the simple square threw early mathematicians into a serious tizzy!

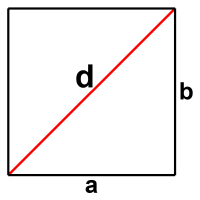

The problem arises when you draw a diagonal line between opposite corners and try to determine the length of the diagonal. Because the corners are all right angles, the diagonal forms a right triangle with the diagonal line as its hypotenuse.

For any right triangle, the Pythagorean theorem says:

And since all sides of a square are equal, and therefore a=b, we can rewrite this as:

And then combine the two like terms to get:

Now we can take the square root of both sides to get:

If the sides of the square have a length of one, then a=1, and we’re left with:

Which was a problem for the ancient Pythagoreans because the square root of two turns out to be what we now call an irrational number. (That means there is no fraction — no rational number — that can express it. It also means that a decimal expression has a non-repeating endless series of digits.)

[The terminology used by the ancient Pythagoreans was to say that the diagonal was incommensurable with the sides. The number was inexpressible and could only be approximated with rational numbers.]

Note that if a, the length of the side, is something other than one, we still have the square root of two, but multiplied by some number, and the result is still irrational. Of course, one could set a to a value that results in a rational product but see below for what happens then.

§

The problem was that the ancient Pythagoreans believed the universe was expressible with rational numbers. There should always be a (perhaps very tiny) rational number that made any length exactly expressible.

The thought of inexpressible numbers was so disturbing to them that, according to legend, they murdered the guy who discovered it, Hippasus of Metapontum, by — because they were at sea at the time — throwing him overboard. (It’s also said that he was merely exiled.)

To be clear, what Hippasus was said to have discovered while on that ship involved the sides of a pentagram, which are also irrational. (It is likely, however, perhaps because of the simplicity of the square, that the square root of two was the first number proved to be irrational.)

Many centuries later, the Arab philosopher Iamblichus wrote:

It is related to Hippasus that he was a Pythagorean, and that, owing to his being the first to publish and describe the sphere from the twelve pentagons, he perished at sea for his impiety, but he received credit for the discovery, though really it all belonged to HIM (for in this way they refer to Pythagoras, and they do not call him by his name).

Pythagoras HIMself predates Hippasus by about a century, so Pythagorean ideas were well set by the time Hippasus upset their apple cart.

§

One might think that setting the diagonal to a rational number, say two, might get us out of this jam. But then we have:

We can square the left side to get:

And then divide both sides by two to get:

And now, taking the square root of both sides, we get:

So, in making the diagonal a rational number, now the sides are irrational.

There’s no escape. The simple diagonal of the simple square leads inescapably to the madness of irrational numbers!

§

We know now that nearly all numbers are, in fact, irrational. The rational numbers, while infinite, are still countable (or more precisely, enumerable). [See More Fraction Fun for details.]

The irrational numbers, however, are uncountable — a different (higher) order of infinity. [See Infinity is Funny for more.] There are infinitely more irrational numbers than rational ones (as weird as that may seem).

§

It’s worth mentioning that the simple circle is also a problem for rationalists. The ration of a circle’s circumference to its diameter is perhaps the most well-known irrational number of them all: pi!

I’ve written about pi (and its double, tau) plenty of times here, so won’t say more here. This post is about squares, not circles!

§ §

Stay irrational, my friends! Go forth and spread beauty and light.

∇

February 26th, 2024 at 12:19 pm

This post is (a) the result of an idle doodle one evening when my mind wandered into the square-diagonal thing, (b) my trying to learn the art of shorter posts, and (c) an effort to write a bunch of Brain Bubbles up to 99 (or maybe 100) and then retire the series (because the notion hasn’t worked out as well as I intended).

February 26th, 2024 at 1:50 pm

The intriguing philosophical thing is this: Were the ancient Pythagoreans right that nature is, in fact, rational?

The irrational numbers, along with the rational numbers, comprise the real numbers, and it’s with the real numbers that all sorts of problems crop up. (And recall that, within the real numbers, the irrational numbers infinitely outnumber the rational ones.)

But it’s possible the real numbers are an abstraction that don’t actually exist in the natural world (just like perfect circles are an abstraction that don’t, indeed can’t, exist in the real world).

Nature being rational, but not real, would solve those issues that arise with irrational numbers.

February 27th, 2024 at 10:57 am

I have a new hobby you might enjoy… 3D printing.

Squares, cubes, spheres, penta-hexa-whata-grams all possible and, through printing, physically palpable.

I’ve designed and printed my own hubs for creating geodesic spheres – 8s & 3s. I think this pastime is right up your alley.

And, they’re cheap. An adequate printer can be had for < $300. And all the software to support them is free.

February 27th, 2024 at 12:52 pm

It’s a cool techno-toy, no doubt — my buddy has one — but I can’t think of any reason to get one myself. I already have shelves and boxes of tchotchkes and souvenirs that I wonder why I still keep. I’ve decided this round of Spring Cleaning is going to see most of them tossed. I bought a scanner a while ago and hardly ever use it. I suspect a 3D printer would go the same route. 🤷🏼♂️

February 27th, 2024 at 1:08 pm

I hear ya.

But, as soon as I started visualizing “things”, actually designing them, printing them and seeing them in real life… I was hooked.

Sure you can download and print a millions doodads. And that’s fun and all. But, it’s the realization of an idea: Can I print a tetrahedron inside a cube, inside a dodecahedron inside a … And have it all work?

Parametric design (using a spreadsheet), and being able to change numbers, changing a design – pop – and then printing it. It’s a different world you won’t understand until you do it.

February 27th, 2024 at 1:55 pm

Oh, I totally get that! Let me ask, I know you’re a software guy, do you have any background in hardware or carpentry or anything like that? What I’m asking is if you have any experience in design and construction. If it’s your first real experience with design and build, I can fully appreciate the fun you’re having right now! Making something you designed can be a heady experience!

I was a (mostly electronics) hardware guy since grade school and learned some carpentry from my dad. I was also involved in designing and implementing stage lighting (mostly plays, some musical performances or dance), and in college I was a film and television major, which involves lots of designs and builds (sets, costumes, etc). I’ve been designing and building stuff all my adult life. Maybe that’s why the idea of 3D printing doesn’t grab me? (Or am I just cynical and jaded? Probably both.)

Totally get parametric design and agree it’s cool. I’m sure we’ve both done that with code we’ve written, and most of my 3D designs use it. For instance, in this 3D model of a telco crossbar switch:

That I’m working on for a blog post (and possibly a YouTube video) I’m planning. (Telco relay-based switching systems have been a fascination of mine for a long time. Very amazing what can be done with relay logic.)

February 27th, 2024 at 6:06 pm

I started out in my 20’s building electronics systems for battery powered forklifts. Lots of soldering, testing, PCB board layout, enclosure design. I also restored old cars with the boss of the electronics shop I worked in. Pre-War BMWs: welding, body work, general mechanicals. And I did stints framing homes and roofing here and there.

The software came later in life – and started with Motorola assembler for a discharge circuit I designed.

But, it’s been decades since any of that. The fact that I’ve had these ideas swirling around and now finally I have both the construction capability and the Arduino coding capability — now’s the time to get this stuff done.

I’d have never done it without my son buying this 3D printer for me for xmas. The tiniest nudge was all it took…

February 27th, 2024 at 7:46 pm

That early stuff sounds cool. Working on cars and building houses are two skills I never had much exposure to (and wish I had — especially the house-building). I have a buddy who’s a bit of a gearhead, and I picked up a few things, but only a few.

For me, software began with a college class (see this post). It was a duck-water experience. The next semester I added a CS minor. It was just a beloved hobby for years, but it eventually became my career. Funny how things happen. (My early assembler was Z80 and 6502. And Donald Knuth’s MIX!)

I’m guessing that some part of the fun for you is doing this with your kid. I’d be way more into doing something like that if I had someone to share the fun with. And, totally, as you say, after decades to have the chance to dive into that design and build cycle. I can definitely see the attraction!

When they get to the point I could make a functioning electronic device… that would be something! It’d be amazing to actually make a working crossbar switch. (Although what’d I do with it…🤔)

February 27th, 2024 at 11:46 am

Oy, math!

February 27th, 2024 at 12:52 pm

Please don’t throw me overboard!! 😯

March 1st, 2024 at 2:23 pm

[…] notes that didn’t make it into my recent post, The Irrational Square (because I forgot I’d jotted them down while thinking about the post — even when I write […]

March 14th, 2024 at 12:19 pm

[…] good old Pythagoras and his famous theorem (which I referenced recently in The Irrational Square). In English, the square of the hypotenuse of a right triangle is the sum of the squares of the […]