One of the Substack blogs I follow, A Piece of the Pi by Richard Green, is almost ideal from my point of view because it features articles that interest me but only — at most — a few a month (so I needn’t strain to keep up).

One of the Substack blogs I follow, A Piece of the Pi by Richard Green, is almost ideal from my point of view because it features articles that interest me but only — at most — a few a month (so I needn’t strain to keep up).

Which matters because keeping up with dozens of science and math blogs, video channels, and occasional papers takes considerable time away from various hobby projects. But sometimes (and this is the third time Mr. Green has done this) something captures my imagination and sends me off on a tangent.

The results often seem worth sharing, and this is no exception. The delight here is that such a simple idea results in a variety of interesting patterns.

You should read the post (and subscribe to the blog if interesting corners of appeal to you), but the short version is that:

- Given a set of N evenly spaced points around a circle,

- Index them from zero to N-1,

- Draw a line from each point at index j (from 0 to N-1),

- To the point indexed by j×M mod N.

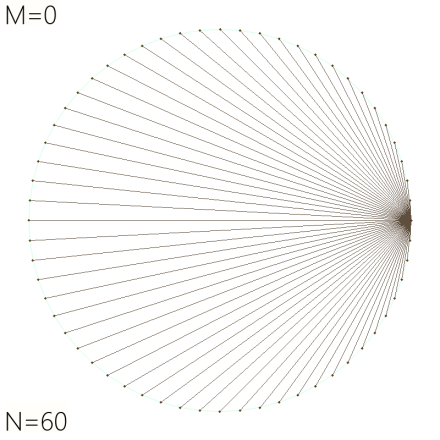

This has a simple idea. A circle and just two parameters: N, the number of points around the circle; and M, the multiplier that determines which point to draw a line to (given the current point around the circle).

The first point, with index zero, never has a line from it because zero times anything is zero, so the line (such as it is) is always from the zeroth point to itself. If the multiplier M is itself zero, all other points have a line to the zeroth point because zero times any index is zero.

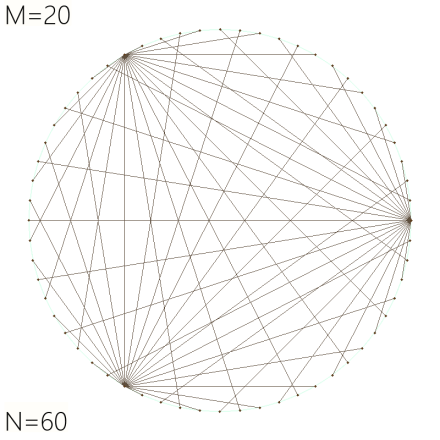

Here’s what that looks like with N=60:

Remember that in geometry, 0° on the circle is at “3 o’clock” and positive angles are measured counterclockwise (negative angles, clockwise). As it happens, these patterns are symmetrical in terms of counter- or clockwise angles, so all that really matters here is that 0° is at “3 o’clock”.

If M=1, then each point has a line to itself because any index times one is that index. So, the image for M=1 is pretty boring:

“Just the dots, ma’am.” Note that making N bigger or smaller just changes the number of dots and what we might think of as the “resolution” of the pattern. (What I mean by this becomes clear below.)

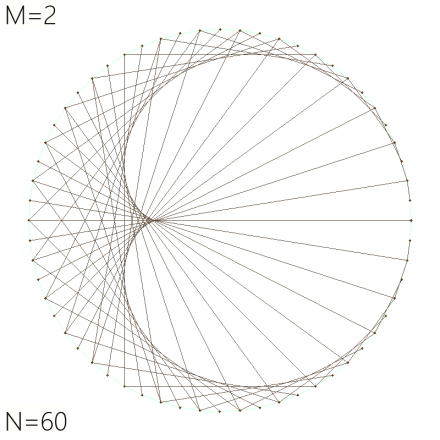

It’s not until M=2 and above that things start to get interesting:

Despite being made entirely of straight lines, a curved shape — a cardioid — emerges from the pattern. Straight rays of light bouncing around inside a round coffee mug create similar patterns (see caustics in optics).

§

Before we continue, let’s take a closer look at the process. While these images are computer-generated, Mary Everest Boole studied them in the late 17th century using cards with punched holes and thread for lines between them. Boole, who was married to that Boole, recommended string art as a way to get kids interested in geometry.

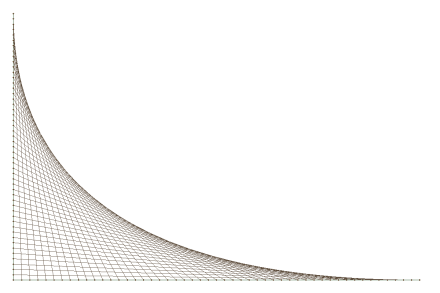

And who among us hasn’t doodled or done this in string:

A graceful curve emerges from a bunch of straight lines. Amazing! 😄

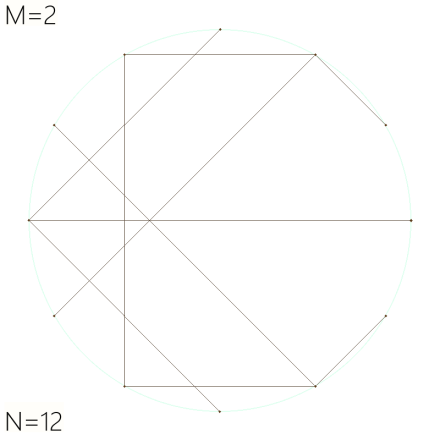

Let’s start with a low resolution one to illustrate the process. Here we’ll set N=12 — like the hours on a clock — and use the first interesting value of M=2:

Let’s take all 12 points in order:

- Zeroth point (at 3 o’clock) connects to itself.

- First point (2 o’clock) connects to second point (1×2).

- Second point (1 o’clock) connects to fourth point (2×2).

- Third point (noon) connects to sixth point (3×2).

- Fourth point connects to eighth point (4×2).

- Fifth point connects to tenth point (5×2).

- Sixth point connects to zeroth point (6×2=12=0).

- Seventh point connects to second point (7×2=14=2).

- Eighth point connects to fourth point (8×2=16=4).

- Ninth point connects to sixth point (9×2=18=6).

- Tenth point connects to eighth point (10×2=20=8).

- Eleventh point connects to tenth point (11×2=22=10).

As I said, very symmetrical.

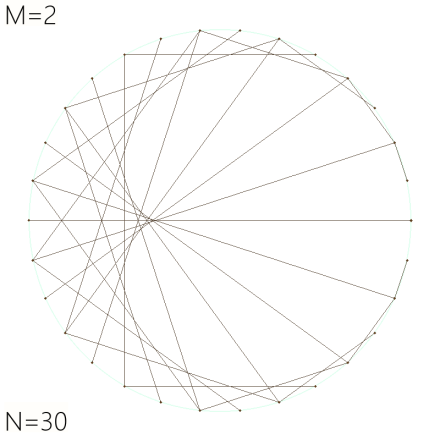

Increasing N just adds more lines allowing the pattern to emerge. It starts to emerge by N=30 but still looks pretty blocky:

As the example above shows that it’s fairly prominent by N=60.

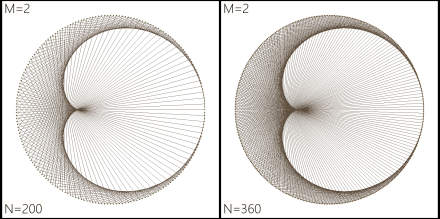

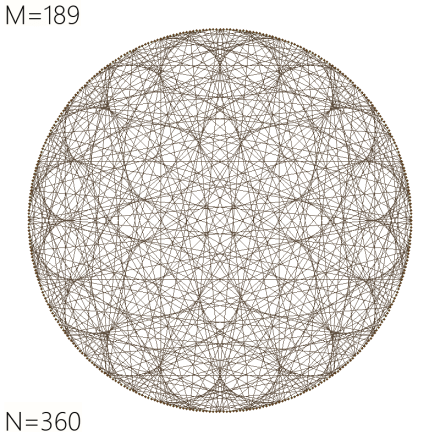

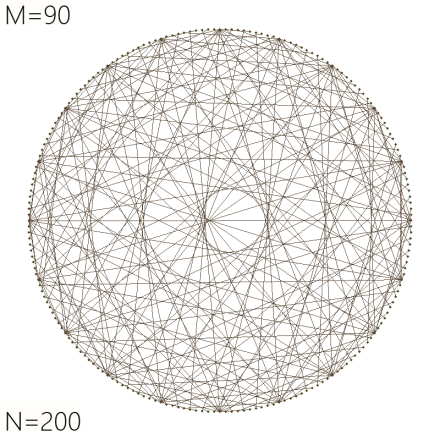

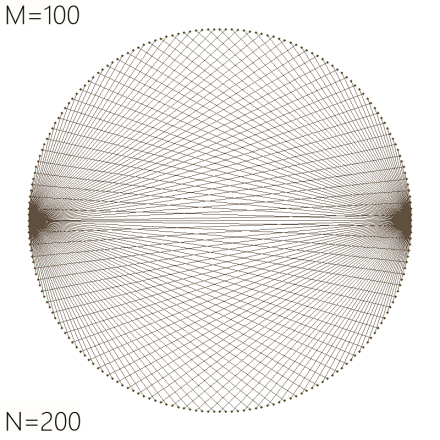

Here, respectively left and right, are N=200 and N=360 (one point every degree around the circle):

Which is interesting enough, curves from lines in a circle rather than between two lines. It’s when we increase M that things start to get interesting.

At first, as we increase M, all that happens is that the pattern develops more “lobes” or “bays” (or whatever you want to call them).

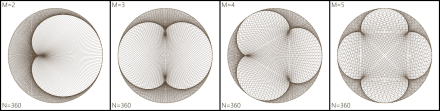

Here are four with M going from 2 to 5:

And from 6 to 12 in steps of 2:

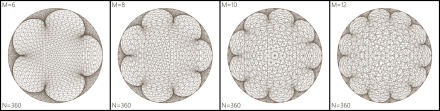

It reminds me a bit of what happens to the Mandelbrot as you increase the exponent that Z is raised to from its normal value of 2 to higher (integer) powers in the equation that determines whether complex coordinate C is in the set or not:

One doesn’t have to use Z², one can use Z³ or Z⁴ or Z⁵ or whatever.

Below are nine renderings of the full Mandelbrot that, from top-to-bottom and left-to-right, start with the normal exponent of 2 and increase it in steps of one up to 10 (note that the number of “lobes” in this case is one less than the exponent):

§

Getting back on point, what’s happening with these stitch graphs is that, as the multiplier increases, the end point of each line rotates further and faster around the circle.

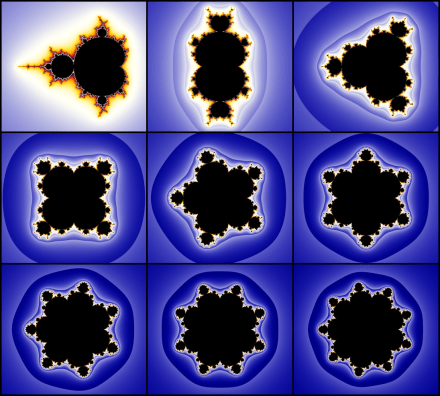

For example, if N=300 and M=100, then — just to pick one — the 42nd point’s line goes to 42×100=4200=0. That’s (exactly) 14 times around the 300-number clock. One might well suspect that M and N values with such a basic ratio (1/3) don’t result in a very interesting — or at least complex — pattern.

One would be right:

The 1/3 ratio is behind that node points at 0°, 120°, and 240° (3 o’clock, 11 o’clock, and 7 o’clock, respectively). The ratio between M and N determines the look or shape of the pattern.

As mentioned above, N just controls the resolution. Here’s the same pattern ratio (1/3) but with M=20 and N=60:

Same three nodal points in the same three positions.

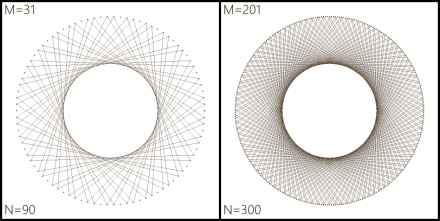

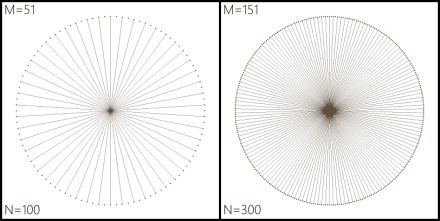

The fun comes from playing around with different values of M (and N, too). Sometimes the lines avoid the center:

And sometimes they all pass through it:

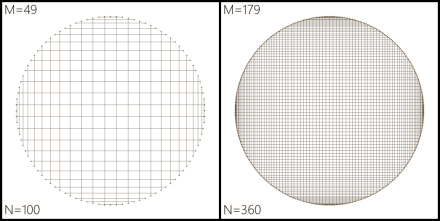

You can even get grid-like patterns:

All depending on the ratio between the values of M and N.

§

That’s pretty much what there is to say. I recommend Richard Green’s article for further details as well as a connection between these patterns and orbiting planets.

§

I’ll end with some of the more interesting and attractive patterns I’ve found so far (some of these are from Green’s post and, as I understand it, from the paper he read that inspired his post).

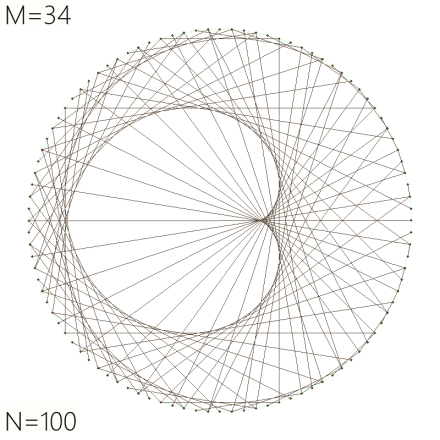

Here’s one that looks like the M=2 example but is more complex because M=34:

With more complex ratios come more complex shapes:

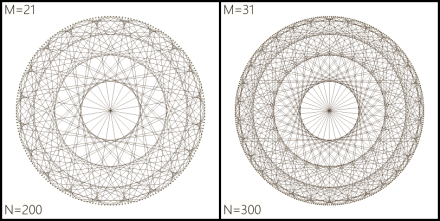

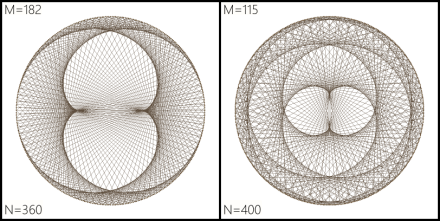

Here are two I especially like:

They have something of a 3D feel to them.

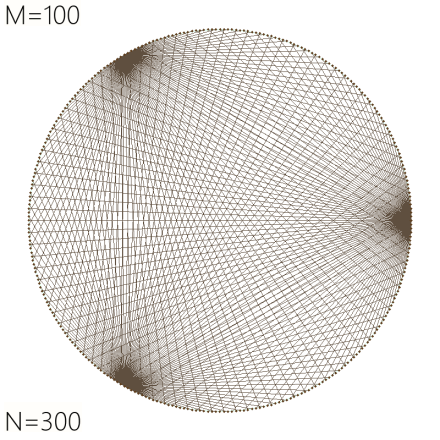

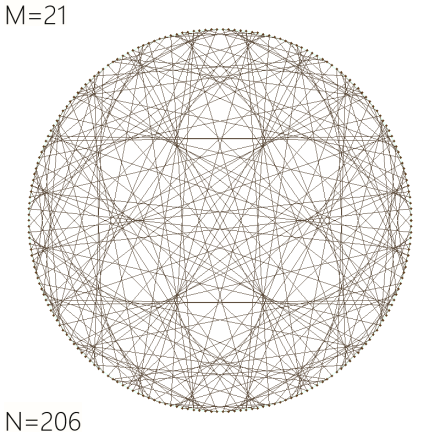

I also really like this one:

And this one:

Or this one:

I’ve seen Middle Eastern art based on patterns like these. An interesting combination of razor-straight lines and graceful curves.

And just to end on a mellow note:

The simplest ratio of all: 1/2.

§ §

Stay straight and curvy, my friends! Go forth and spread beauty and light.

∇

December 12th, 2025 at 12:44 pm

M=189/N=360 looks like a church window to me, especially with the four “chalices” around the innermost third. I love all of these! It’s so mind bending and beautiful to see visual representations of mathematical concepts. I’m not a math/science person, but I love the logic and simplicity of complexity crystallized into clear form before my eyes.

December 12th, 2025 at 2:04 pm

Yeah, it does look like a church window. Richard Green’s post has a link to an online tool you can use to make your own:

https://times-tables.lengler.dev/

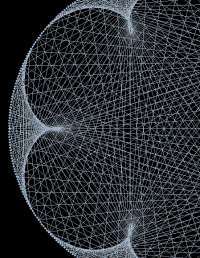

It uses a black background with either white or colored lines. If I have another go at my code, I’d like to add colored lines (and maybe also “dark mode”). What’s interesting about the online tool is that you can rotate the patterns in 3D. It uses a second circle “below” the primary circle as the target for the lines. Switch the camera to perspective and front view to see it best.

December 12th, 2025 at 5:14 pm

Cool!😎

December 12th, 2025 at 2:07 pm

P.S. If you like interesting patterns from simple mathematics, check out Euler Spirals and Pi Paths from four years ago.

January 23rd, 2026 at 9:14 am

[…] the Modular Curve Stitching post last December, I showed diagrams I’d made. I later found out there is a website that […]