It’s been a while since my last Sidebands post. That’s partly because I’ve been working on a project that I’m sure will become a multi-post series and thought it would be nice to start with #81. But I’m not done (or actually started on the writing) yet, and this one has also been lurking for a while.

It’s been a while since my last Sidebands post. That’s partly because I’ve been working on a project that I’m sure will become a multi-post series and thought it would be nice to start with #81. But I’m not done (or actually started on the writing) yet, and this one has also been lurking for a while.

Essentially, I needed to figure out how to join a cone to a sphere in a seamless way (as in the picture here). This requires the sides of the cone meet the sphere at a tangent point.

It’s yet another case of actually needing the trigonometry I learned in school.

This need came up last March in my Where is the Platonic Realm? post over on my Substack blog. The post addressed the ago-old question about the reality (or lack thereof) of the Platonic Realm.

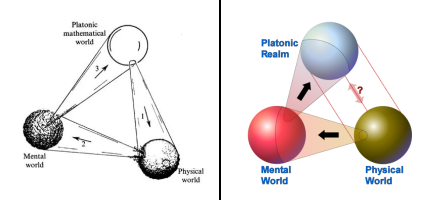

The post in part riffed on a diagram I’d seen Roger Penrose use in several of his books:

On the left, Penrose’s diagram showing the relationships between the Physical World, the Mental World, and the Platonic Realm. On the right, a more colorful (and slightly adjusted) version I made using a 2D paint program.

I’m not going to discuss the Platonic Realm here. If interested, see the Substack post.

One thing to notice here — the thing relevant to this post — is how the cones linking worlds expand such that their bases exactly encompass the spheres. Geometrically, the cone sides meet the sphere at a circle of tangent points on the sphere.

The 3D modeling tool I use, POV-Ray, requires four parameters to define a cone shape:

- base X, Y, Z coordinates

- base radius

- top X, Y, Z coordinates

- top radius (zero for pointy tip)

It’s similar to defining a cylinder by its end points and radius, but with two radii, one for each end. I need the end points and base radius (I can assume the cone’s tip is pointy). I can place the cone tip at the center of the sphere the cone “emanates” from (the source sphere), which gives me one easy end point.

The problem is the base end point and radius. A simple (but unsatisfactory) approach is to put the cone’s base at the center of the target sphere. But this is unsatisfactory because the cone does not meet the sphere at a circle of tangent points:

The cone disappears inside the sphere, and the points where it does are clearly not tangent points. (That the cone sides go into the sphere means they cannot be tangent.)

I couldn’t quite solve it back in March, so I went with the simple (unsatisfactory) version:

(I’ll again refer you to the post if you’re curious why there are now four worlds or why they’re in a line.)

As you can see, the cone sides go into the spheres. It was (just barely) acceptable for the post, but I wasn’t thrilled. I wanted my tangent cones. And I wanted to solve the problem.

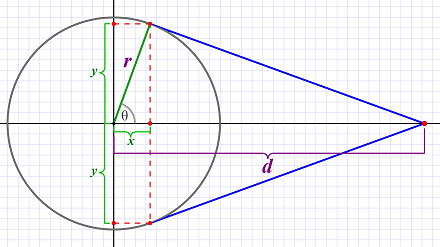

Which seemed to look like this:

I needed x and y (or possibly just the angle theta). The x value would determine the cone’s base point, and the y value would determine its radius. But all I had was the distance d and the sphere’s radius r (which we can assume is 1.0 for simplicity).

It seemed the crucial requirement was the [x, y] point where the cone’s sides touch the sphere. Or maybe it was the angle theta (θ) from which I could get x=cos(θ) and y=sin(θ). But I found myself a bit stuck on how to fine either of those. The only other apparent fact is that the cone’s side (blue line) meets the radius (green line) at a 90° angle — the very definition of a tangent.

But everything seemed to revolve around finding either theta or, if not that, in some other fashion finding x and y. Perhaps if I were a better mathematician the solution would have been readily apparent, even trivial, but I’m not, and it wasn’t.

There were two obvious edge cases:

Firstly, the case where the cone has zero length. It would be located on the sphere itself, and the tangents would be vertical lines. So, this case has x=1 and y=0. The angle theta (green line) would be zero.

Secondly, the other extreme:

Now the cone’s tip is infinitely far away, and the tangents are straight horizontal lines touching the top and bottom of the sphere. Now, x=0, y=1 (and -1), and theta is 90°.

All other cases fall between these two (impossible) extremes.

One other case seemed helpful because it was easy to see what it should be:

If we set theta to 45°, then x and y are both simply 1/√2 (with y having both positive and negative values). Even better, the cone’s sides must be at a 45° angle (because they’re necessarily perpendicular to the radius at that point). That means the cone’s tip has to be 2x from the center.

The problem here is that we’re starting with the angle theta, and that’s the thing I need to figure out for a given cone tip distance. As it turns out, starting with theta does lend itself to fairly easily deriving the distance d, but that’s not what I needed.

I thought, though, that if I could figure out the math behind this case, maybe I could figure out how to solve what seemed the much harder case. I started with the blue cone line being perpendicular to the green radius line. The slope of the green line is y/x or tan(θ) (alternately sin(θ)/cos(θ) because that’s the same as y/x).

The perpendicular slope of the blue line then is x/y or cot(θ) — alternately cos(θ)/sin(θ). The x value, of course, is cos(θ). That means the cone’s length extends from x to where the blue line meets the X-axis. That blue line starts at a height of y above that axis, and its slope determines how far it must go to reach the X-axis:

Where CBR is cone-base-radius — which is sin(θ) — and CS is cone-slope — which is cot(θ) — and d is the distance from the cone’s base to its tip. We can rearrange this:

And then to:

We know cot is cos/sin and that dividing by a/b is the same as multiplying by b/a, so:

The cone’s base starts at x — cos(θ) — so the actual distance from the sphere’s center to the cone’s tip is:

Which is just great if I want to start with theta and derive the distance to the cone’s tip (which I don’t). I did do some renderings to test my math, though:

I used semi-transparent cones so I could see several sizes at once. I was bothered by the visible rings where the cone touches the sphere but decided it was probably an interaction between two the objects. Sure enough, with an opaque surface texture:

Seamless! The lede picture for this post shows another example with a shorter cone.

But still not what I need.

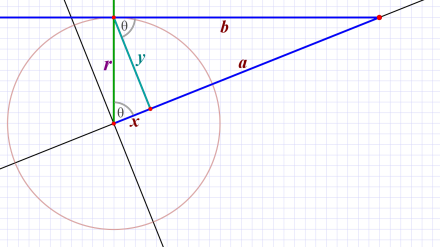

I was mucking about with the above formula trying to find a way to make it do what I wanted and happened to redraw things in a way that gave me an idea:

What I noticed is that the two triangles are congruent — not just both right-angle triangles but sharing all the same angles. That means:

Since we’re looking for the value of a, we can rearrange this to:

And because x=cos(θ) and y=sin(θ), this becomes:

Verifying the math above (which is nice but still doesn’t help me find the tangent point).

It did get me thinking more about the triangles, and that led to this:

If I rotate things so that the tangent point is at the top of the circle, finding that tangent point is trivially easy. It’s just a horizontal line at the radius. The line into the sphere’s center is also simple (and is the former X-axis). I know the radius r and the distance d (which is x+a in the diagram above, so a is just d–x). This lets me calculate b using Pythagoras:

I don’t know x, y, or a, yet, but now I do have all three sides of the outer triangle: d (x+a), b, and r:

And note that the triangle is not a right triangle, so the usual trigonometry tricks won’t work here. But the Law of Cosines will. Given a (non-right) triangle:

We have three equalities:

We’re interested in the one labeled alpha (α) above — that’s our theta. We can rearrange the second Cosine Law to get:

In the examples shown above, r=10 and d=25 (or you can scale it down to a unit circle with r=1.0 and d=2.5). This means b is:

And then theta is:

And now we can calculate x and y:

And now we have what we need to position the cone, so we’re done!

§ §

Stay calculating, my friends! Go forth and spread beauty and light.

∇

June 25th, 2025 at 5:13 pm

Oh, damn. I hit that too-damn-obvious Publish button before I finished the post. But it’s done now.

June 27th, 2025 at 9:19 am

Do I understand this post? No. But was it fun to read? Yes!😀

June 27th, 2025 at 4:58 pm

Well, I’m glad you enjoyed it!