You may remember learning way back in grade school that you can’t divide by zero. You may remember being told that division by zero is undefined. But have you ever wondered why we can’t divide by zero? Couldn’t the answer just be zero? We get zero when we multiply by zero, so why not when we divide?

You may remember learning way back in grade school that you can’t divide by zero. You may remember being told that division by zero is undefined. But have you ever wondered why we can’t divide by zero? Couldn’t the answer just be zero? We get zero when we multiply by zero, so why not when we divide?

But dividing is the opposite (or inverse) of multiplying, so if multiplying by zero gives zero, then maybe dividing by zero gives us… infinity? But infinity isn’t a number (it’s an idea), so that doesn’t work, either.

In this post I’ll dig into why division by zero is undefined.

An easy way to see the problem is through the long division process we learned back in the same grade school that taught us we can’t divide by zero.

Before we get started, to make sure we’re all on the same page, we can write a division problem in (at least) three ways. One is the long division process we’re about to explore, and it’s the only one of these three that enables the calculation of a decimal answer. For example, we can write 1 ÷ 4 = 0.25, but it takes long division (or a calculator) to determine the answer on the right.

The paragraph above contains a second way: using the division symbol (÷). The horizontal line, with one dot above and one below, represents the third way to represent a division: as a fraction. All three ways involve the same two numbers:

(LaTeX doesn’t have a good way (that I know of) to represent the long division, so I did the best I could to show it. You may have to use your imagination a little.)

One thing to remember here, a fraction is a division.

§ §

Getting back to long division, let me start with a very simple example, 8 ÷ 2, which we know is exactly 4, because two goes into eight exactly four times. Another way to figure it — because division is serial subtraction — is that we can subtract two from eight four times (with nothing left). In both cases, then, the answer is exactly four.

Figure. 1

The long division process breaks a division into a series of smaller parts. In this case, 8 ÷ 2 (see Figure 1.), the dividend, the eight, goes inside the lines on the right while the divisor, the two, goes outside on the left.

This may feel backwards from the 8 ÷ 2 way of writing it. It may also feel backwards compared to the 8/2 way of writing the division as a fraction. One has to think right-to-left when reading the division “eight divided by two.” So, just be aware that it’s easy to get turned around with long division.

Once we’ve written the division, we can proceed with the calculation. First, we ask if the divisor “goes into” the dividend and, if so, how many times. For this, the divisor must be smaller than the dividend. In this case, two is smaller than eight, so we can continue. And it’s easy to see that two goes into eight exactly four times. (Or can be subtracted from eight exactly four times.)

So, we write a four above the dividend (8), multiply it times the divisor (2) to get 8, and we write that below the dividend. Then we subtract this from the dividend, and the result is zero. That means we’re done and have an exact answer (4).

§

That calculation had only one part, and it was easily done, but this is just a starting point. Now, let’s try something with multiple parts.

Figure 2.

Let’s reverse the above division and see what we get with 2 ÷ 8. (See Figure 2.) The answer might not spring to mind immediately this time — we might need long division to figure it out.

This calculation ends up having three parts (which correspond to the three digits in the answer).

In the first part, we see that eight does not go into two, so we write a zero above it. Zero times eight is zero, so we write a zero below the two and do the subtraction.

Which gives us two again. Which isn’t zero, so we must continue. We bring a zero down from the dividend (we add zeros for each part after the first in long division). That dropped down zero makes the new dividend twenty.

In the second part, we see that eight goes into twenty twice, so we write a two above and a sixteen (two times eight) under the twenty. This time the subtraction gives us four. Which isn’t zero, so we’re not done. We bring down another zero to turn the four into a forty.

In the third part, we see that eight goes into forty (exactly) five times. We write the five above and the forty below. This time the remainder of the subtraction is zero, so now we’re done, and the answer is 2 ÷ 8 = 0.25.

§

But what happens if we try to divide something by zero?

Figure 3.

Let’s try dividing eight by zero (8 ÷ 0). As Figure 3 shows, this doesn’t work. As it turns out, we can get any answer we want.

We start, as always, by writing the dividend (8) on the right inside the lines and the divisor (0) on the left outside the lines.

Now we ask how many times zero goes into eight. Alternately, how many times can we subtract zero from eight? Apparently, the answer is as many times as we like. In this first round, let’s try eight, so write eight above the dividend and eight times zero (=zero!) below it. We subtract zero from eight and end up with eight again.

Which should right away show us this is futile. We’re right back where we started, dealing with eight. But let’s continue for two more steps and try some different partial quotients (the digits above the dividend that comprise the answer).

The procedure requires we drop down a zero, so now the dividend is eighty, and we have the same problem, only bigger. How many times does zero go into eighty? Eight didn’t buy us much, so let’s use the highest possible digit: nine. But nine times zero is again zero, and now the subtraction leaves us with eight hundred. Our problem is even bigger!

The remainder will continue to grow for however long we try to carry on. Worse, we obviously can use any quotient digits we want. It seems the answer to 8 ÷ 0 is all possible answers.

Bottom line, long division breaks down and is useless when dividing by zero.

§ §

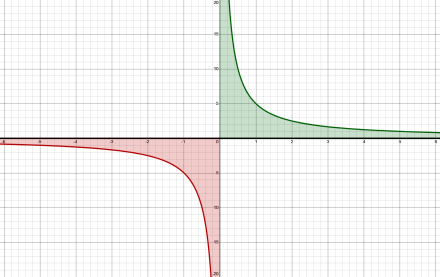

What about the fractional representation? Is there any meat on that bone? We could try graphing n/x for some constant n and see what happens at x=0:

Figure 4. Graph of n/x (for n=5).

As x approaches zero, the value of n/x approaches infinity. In calculus terms, we say that the limit of n/x, as x approaches zero, is infinity. This has led to the suggestion that division by zero returns infinity. But infinity isn’t an actual number, so the idea is already in trouble.

More importantly, as the graph shows, n/x approaches negative infinity when x approaches zero from the negative side (red part of the graph). So, division by zero, when viewed as a limit, seems equal to both positive and negative infinity. (And, by the way, which infinity n/x approaches reverses when n is negative.)

Additionally, dividing any value by zero returns ±infinity, which is just as unhelpful as division by zero returning zero.

[One might argue this favors the n/0=0 interpretation because zero is between negative and positive infinity, so we could take their average. But we’ve already seen that a result of zero isn’t useful.]

So, the fraction n/0 also shows the problem with dividing by zero.

§ §

Another way to demonstrate the impossibility of division by zero looks at the operation of multiplicative inverses that transform the division answer back into the divisor or dividend (depending on which term is inverted).

In general, the multiplicative inverse of a number n is 1/n:

(The inverse of n can also be written as n-1.)

If we multiply any number by its multiplicative inverse, we get one:

One is the multiplicative identity, a cornerstone of multiplication. (Multiplying any number by one just returns that number.)

§

More to the point, if we multiply the result of a division by the multiplicative inverse of either of the two division terms, we get the other division term. Let’s return to the division problems from above and work them as fractions.

The first, 8 ÷ 2, we write (and solve!) like this:

Note how we split the single fraction, 8/2, into two fraction terms, 8/1 and 1/2. That allows us to express the division as a multiplication because 8 ÷ 2 is exactly the same thing as 8 × 1/2. Put formally, dividing a by b and multiplying a by 1/b are the same operation.

Now, if we multiply the answer, 4, by the inverse of either term of the multiplication, we get the other term:

And we do.

§

The next problem 2 ÷ 8, we write like this:

Note that 8 ÷ 2 and 2 ÷ 8 are the inverse of each other. This is readily apparent when we express the divisions as fractions: 8/2 and 2/8 are obviously each other’s inverses. That means their answers, 4 and 0.25 should be inverses, and this is also readily apparent when writing them as fractions: 4/1 and 1/4.

Which means this next step is the inverse of doing it in the first example (everything is “upside down”):

And again (of course), we got the expected result.

§

But when we try it with the third example, 8 ÷ 0:

For one thing, we ended up with what we started with (8/0) and then assumed it was equal to zero. But now we find that assumption means:

The first one works out okay (on the assumption that 1/0=0). We get back the second term, the divisor zero. But the second one fails. We expect to recover the 8/1 term, but we get zero again. (And in this case, we’re dividing by one, so the math is solid but returns the wrong answer.)

So, again, our process breaks down with division by zero.

§ §

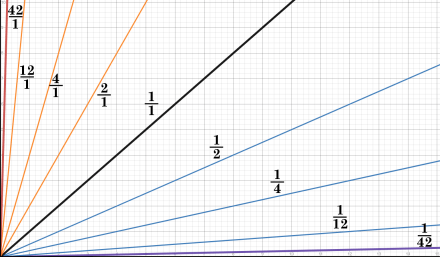

The last demonstration of the problematic division by zero has to do with slope:

Figure 5. Some lines with different slopes.

Which has nearly the same mathematical sense as it does when we refer to the slope of a hill going up (or down). We define it as the change in y divided by the change in x:

The Greek letter capital delta (Δ) in this context is taken to mean “change in”. This definition also makes clear the connection between slope and division. Slope is a fraction, and a fraction is division. (Note that slope will be negative (“downhill”) when delta-y is negative.)

More importantly, consider the slope of a line, y/0 for any non-zero value of y. As shown in Figure 5, the larger the fraction, the steeper the slope. We’ve seen above that, as x approaches zero in n/x (or in this case, y/x), the value approaches infinity. Which means the slope approaches infinity — a vertical line.

But such a slope is a problem because it can’t be quantified. The delta-y can be anything we want, and thus is useless. Infinite slope, because it has a division by zero, is undefined.

§ §

Bottom line, division by zero is undefined. It can provide no meaningful answer. Zero “goes into” a non-zero number as many times as we like, from zero to infinity.

[Division by zero is the secret trick embedded in many of those cute “proofs” that 1=0. In slipping a hidden division by zero into the steps, all bets are off, and the “proof” can “prove” anything.]

There is a single exception to all this: 0 ÷ 0 = 0. This is allowed because it doesn’t break anything.

Stay defined, my friends! Go forth and spread beauty and light.

∇

January 23rd, 2024 at 11:01 am

There is another exception, but it doesn’t apply to normal math. The Zero ring is a set containing only the number zero — depicted as: {0}.

In this case, the answer to any operation is zero, and all the numbers are zero. So, division by zero is fine in the Zero ring.

January 23rd, 2024 at 11:04 am

Incidentally, when mathematicians talk about a “singularity” they mean the sort of thing that happens with n/x as x approaches zero.

February 13th, 2024 at 1:49 pm

[…] You may have, at some point, seen one of those bits where a series of seemingly simple math operations somehow end up proving that 1=0 or something equally clearly wrong. Most of them accomplish their joke by sneaking in a hidden division by zero. From that point on, all bets are off (see Divide by Zero). […]

May 7th, 2024 at 8:35 pm

[…] that 2=0 (an alternate version “proves” 1=0 using the same trick: a covert division by zero, an operation whose undefined result breaks the chain of […]