Back on Tau Day (which is also my retirement anniversary), I posted about a scene in the superhero comic Invincible that involves a baseball orbiting the Earth at a very close distance (roughly airplane height). Regardless of superhero strengths, I found the scene impossible on multiple counts.

Back on Tau Day (which is also my retirement anniversary), I posted about a scene in the superhero comic Invincible that involves a baseball orbiting the Earth at a very close distance (roughly airplane height). Regardless of superhero strengths, I found the scene impossible on multiple counts.

At the time, I could only calculate the velocity of the ball given the circumference of the Earth and some guesses about the length of the presumed orbit. Suffice to say the answers sufficiently demonstrated the impossibility.

Here, I’ll use orbital mechanics for some hard data on putative baseball orbits.

The starting point was the Earth’s circumference, 25,132 miles, and dividing it by a reasonable number of minutes to wait for the ball to make the trip:

- 2 minutes: 753,982 MPH (0.112% lightspeed)

- 3 minutes: 502,654 MPH (0.075% lightspeed)

- 5 minutes: 301,592 MPH (0.045% lightspeed)

These speeds are way (way!) beyond Earth’s escape velocity of 25,000 MPH, so there’s no way the ball would stay in orbit. It would vanish into space. Assuming it survived moving at those speeds through any distance of atmosphere.

I didn’t mention this in the other post, but, per Wikipedia, the Solar system’s velocity around the galaxy is about 514,000 mph. The article even mentions that an object could circle the Earth’s equator in 2 minutes and 54 seconds, which correlates with the three-minute roundtrip in the list above.

Which means that, not only would the baseball escape Earth’s gravity, but it would also likely escape the Solar system’s gravity (at Earth’s orbital radius) of 95,000 MPH. The Sun has an escape velocity of 1,381,137 MPH at its surface but that drops to 169,924 MPH by Mercury’s orbit, so the ball would have to come to a point inside Mercury’s orbit to orbit or be captured by the Sun.

In any event, the ball is definitely not orbiting the Earth.

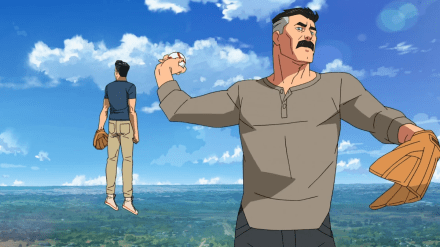

In the comic, they’re in costume (see image above), but in the Amazon Prime animated TV adaptation they’re not.

The obvious next question is — assuming air resistance issues are ignored — how long does the orbit take?

An important point at this point is that a given circular orbit is entirely fixed in terms of its radius, period (length of time), and velocity. Change any one of those three, and the other two necessarily change.

For Mark and Nolan’s game of catch, we’re given a radius based on how high above the ground we guess they are. This fixes the ball’s necessary velocity and the length of time it takes to orbit. As it turns out, the ball and the International Space Station (ISS) have nearly the same orbits.

Which isn’t surprising. The 417 km height of the ISS orbit, compared to the 6371 km radius of the Earth, makes the space station’s radius only 6.5% larger. Looking at it from the ISS, the Earth’s surface is about 94% of the station’s radius. Which means the orbital period of the ball should be roughly 94% of the ISS’s.

§

The formula for orbital period is:

Where T is the orbital period in seconds, a is the orbit radius in meters, G is the gravitational constant (6.6743×10⁻¹¹ N·m²·kg⁻²), and M is the mass of the body in kilograms (in this case, the Earth).

Plugging the Earth’s radius (6.371×10⁶ m) into the formula, we get 5060 seconds, or 84 minutes. The ISS has an orbital period of 93 minutes, so the math checks out give or take a few cents.

Bottom line, the only way Mark and Nolan could be playing catch is if they wait an hour-and-a-half between throw and catch.

§

Two formulas let us calculate orbital velocity, one from mass and radius, the other from radius and period.

Here’s the formula for orbital velocity given mass and radius:

Where v is the velocity in kilometers per second, G, a, and T are as described above. The quantity mu (µ), the product of G and M, is apparently easier to measure more accurately than either G or M alone.

Here’s the orbital velocity formula given radius and period:

With parameters already described.

Since we know both the radius and period of our orbiting baseball, we can use either formula to derive its speed. Both give us a velocity of almost 17,700 MPH.

Which is probably enough to destroy the ball from air friction. More importantly, air resistance would quickly slow the ball down to some much slower terminal velocity. At which point it would fall to Earth.

Here’s a graph showing how orbital velocity varies with orbital radius:

The horizontal axis is the orbital radius in meters, the vertical axis is the orbital velocity in meters per second. You can see the relationship is not even close to linear. As a reference point, the vertical black line demarks the geosynchronous orbital radius (and the red line, the velocity). Note how the velocity falls off slowly at greater radii but rises sharply for closer radii.

§

We can also ask, given a period of 2, 3 or 5 minutes, is there an orbital radius and velocity that lets us play catch?

For this we need the orbital radius formula:

Which uses terms described above. If we assume an Earth mass and plug in 2, 3, and 5 minutes, we get:

- 2 minutes: 525 km @ 61,589 MPH

- 3 minutes: 689 km @ 53,803 MPH

- 5 minutes: 969 km @ 45,379 MPH

Now all we need is a very dense tiny body with Earth’s mass but a radius of 500 km or so (about 8% of Earth’s).

Here’s another interactive graph, this one for orbital period:

The horizontal axis is orbital period, and the vertical axis is orbital radius. The horizontal green line is the surface of the Earth. Orbital radii below that are inside the Earth (or around a much smaller equally massive body as in the example just above).

Note how the curve is steepest when the radius is small, but it flattens out as the radius increases. The period/radius relationship also isn’t linear.

We can use the formulas to create a table for various orbits:

| Orbit | Alt (km) | Radius (km) | Period (min) | Speed (km/s) | Speed (MPH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catch 2 | 526 | 526 | 2.000 | 27,532.798 | 61,589.217 |

| Catch 3 | 689 | 689 | 3.000 | 24,052.115 | 53,803.137 |

| Catch 5 | 969 | 969 | 5.000 | 20,286.339 | 45,379.323 |

| Catch 10 | 1,538 | 1,538 | 10.000 | 16,101.278 | 36,017.593 |

| Surface | 0 | 6,371 | 84.346 | 7,909.926 | 17,694.030 |

| Catch (lo) | 3 | 6,374 | 84.406 | 7,908.034 | 17,689.798 |

| Catch (hi) | 11 | 6,382 | 84.558 | 7,903.312 | 17,679.234 |

| Elevator | 121 | 6,492 | 86.754 | 7,836.046 | 17,528.765 |

| LEO (lo) | 200 | 6,571 | 88.349 | 7,788.619 | 17,422.674 |

| LEO (hi) | 2,000 | 8,371 | 127.034 | 6,900.611 | 15,436.253 |

| Geosync | 35,786 | 42,157 | 1,435.678 | 3,074.973 | 6,878.531 |

| Moon | 362,600 | 368,971 | 36,215.468 | 1,048.485 | 2,345.399 |

The first four entries represent a game of catch with various orbital periods. The altitude and height are the same on these lines because I assumed a point source with Earth mass. Any equally massive body with a surface radius below the various catch radii would work.

The rest of the table indicates both orbital radius and height above Earth’s surface. Note how close the lower orbit periods are. It’s not until we get into high LEO that the orbital period starts to expand (never mind the oxymoron of a high low Earth orbit).

§

I discovered something very interesting while looking into theoretical surface orbits. The planets of the Solar system all have roughly similar surface orbital periods:

| Planet | Period (mins) | Speed (km/s) | Mass (kg) | Radius (km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 85.02 | 3.01 | 3.30e+23 | 2439.70 |

| Venus | 86.50 | 7.33 | 4.87e+24 | 6051.80 |

| Earth | 84.35 | 7.91 | 5.97e+24 | 6371.00 |

| Mars | 99.85 | 3.55 | 6.42e+23 | 3389.50 |

| Jupiter | 171.98 | 42.57 | 1.90e+27 | 69911.00 |

| Saturn | 238.93 | 25.52 | 5.68e+26 | 58232.00 |

| Uranus | 175.72 | 15.11 | 8.68e+25 | 25362.00 |

| Neptune | 154.75 | 16.66 | 1.02e+26 | 24622.00 |

| Pluto | 145.46 | 0.86 | 1.30e+22 | 1188.30 |

| Moon | 108.33 | 1.68 | 7.34e+22 | 1737.40 |

The larger planets naturally have longer periods, but I was surprised at how close they are, nevertheless. The longest, Saturn, is only 2.8 times the shortest, which happens to be Earth.

Of course, since the planetary radii vary considerably (as do their masses), the orbital speed is quite different from planet to planet. Here, the fastest, Jupiter, is almost 50 times faster than the slowest, Pluto (whose 0.86 km/s surface orbit velocity makes it a notable anomaly compared to the others). If we elide both Pluto and the Moon, then Jupiter is a bit more than 14 times faster than Mercury — still a much wider range than for orbital period.

I found that all interesting.

§

Two last formulas, the first for escape velocity from a given mass at a given distance:

Where d is the distance from the mass, M. (Note again the GM product known as mu.)

We can, for instance, plug in the Earth mass (5.9724×10²⁴ kg) and its radius (6.371×10⁶ m) to get the surface escape velocity, 11,186 m/s (25,000 MPH).

We can also plug in the mass of the Sun (1.988×10³⁰ kg) and the distance of Earth’s orbit (1.47×10¹¹ m) to get the escape velocity from the Sun from Earth’s orbit, 42,479 m/s (95,000 MPH).

The second formula is for calculating the gravity for a given mass at a given radius:

(Again, our old friend GM=μ.) If we use the mass and radius of a given body, we can calculate the surface gravity. For instance, using the Earth’s mass (5.9724×10²⁴ kg) and radius (6.371×10⁶ m), we get a surface gravity value of just under 9.820582.

§ §

Lastly, for those of you who dabble in Python, here’s a simple implementation of the formulas you can use for your own calculations:

002|

003| G = 6.67430e-11 ### units: N * m^2 * kg^-2

004|

005| def SurfaceGravity (mass, radius):

006| ”’Return surface gravity given body mass and radius.”’

007| # lambda m,r: ((G*m)/pow(r,2))

008| p = G * mass

009| q = pow(radius, 2)

010| return p/q

011|

012| def EscapeVelocity (mass, radius):

013| ”’Return escape velocity given body mass and radius”’

014| # lambda m,r: ((2*G*m)/r)

015| p = 2 * G * mass

016| q = radius

017| return sqrt(p/q)

018|

019| def OrbitalVelocityR (mass, radius):

020| ”’Return orbital velocity given body mass and radius.”’

021| # lambda m,r: sqrt((G*m)/r)

022| p = G * mass

023| q = radius

024| return sqrt(p/q)

025|

026| def OrbitalPeriod (mass, radius):

027| ”’Return orbital period given body mass and radius.”’

028| # lambda (2*pi*sqrt(pow(r,3)/(G*m)))

029| p = pow(radius, 3)

030| q = G * mass

031| return 2 * pi * sqrt(p/q)

032|

033| def OrbitalVelocityT (radius, period):

034| ”’Return orbital velocity given orbit radius and period.”’

035| # lambda r,t: ((2*pi*r)/t)

036| p = 2 * pi * radius

037| q = period

038| return p/q

039|

040| def OrbitalDistance (mass, period):

041| ”’Return orbital radius given body mass and orbital period.”’

042| # lambda m,t: pow((G*m*pow(t,2))/(4*pow(pi,2)), 1/3)

043| p = G * mass * pow(period, 2)

044| q = 4 * pow(pi, 2)

045| return pow(p/q, 1/3)

046|

047|

Each function also has, in a comment, a one-line lambda version.

Stay in orbit, my friends! Go forth and spread beauty and light.

∇

July 21st, 2024 at 12:48 pm

ATTENTION: The WordPress Reader strips the style information from posts, which can destroy certain important formatting elements. If you’re reading this in the Reader, I highly recommend (and urge) you to [A] stop using the Reader and [B] always read blog posts on their website.

This post is: Orbital Mechanics

July 21st, 2024 at 12:50 pm

For a number of reasons, I’m beginning to think I’m done with WordPress. After 13 years, maybe it’s time to move on. I’m finding Substack a lot more interesting than WordPress these days. I’m ever more seriously thinking of jumping ship.

July 21st, 2024 at 2:00 pm

Here’s a table that shows the orbital speed for the Sun in steps of Solar radii:

The last line shows the orbital velocity at Mercury’s orbit. Based on the table and a baseball speed of 500,000 MPH, the ball would have to travel within three Solar radii to be captured by the Sun. So, bottom line, the ball is almost certainly leaving the Solar system.