I don’t mean the social kind of integration, which I learned as a child, but the mathematical kind of integration, which I never learned in any of my math classes. I didn’t even take calculus until The Company sponsored some adult education classes for employees.

I don’t mean the social kind of integration, which I learned as a child, but the mathematical kind of integration, which I never learned in any of my math classes. I didn’t even take calculus until The Company sponsored some adult education classes for employees.

But those calc classes only got me through basic derivatives (of polynomials, mostly), so integration has been a bit of a mystery to me. Lately, though, I’ve been trying to pick up the basics.

This post just records my first attempts — my math lab book, so to speak.

This story begins with the Cones Can Fool You! post last month, which was about the beguiling volume of cone-shaped glasses. Central to that post was the formula for the volume of a cone:

I’d seen an example of using integration to find a volume formula (I forget of what), and I got to wondering if I could derive that cone volume formula through integration (which I have no experience with).

As it turned out, I couldn’t. But I got close. Ultimately, I had to turn to the interweb for an answer (see Cone Volume below). In retrospect, I like to believe I would have gotten it eventually.

More happily, and why I can finally post this, is that just last night I finally got the one involving slicing a sphere to derive the sphere volume formula (see Sphere Volume 2 below).

My first approach didn’t work at all (though it might have given a numerical answer). I banged my head fruitlessly against what seemed a better approach for several days. I finally got a whiff of my prey, and a focused hunt last night captured it. Which was cool, even though this is entry-level calc — something a high school math student would likely find trivial (and indeed most of these really are).

Circle Circumference

Using the radius of a circle, and that it is 2π radians around, we can trivially derive the circle circumference formula by integrating a circular line 2π radians long.

Conceptually, we want:

Where r is the circle’s radius. The above is also an implementation, so we can proceed directly to moving the r (which is constant for a given circle) out in front:

Then we calculate the anti-derivative of 1 (which is x) and box the integration:

This evaluates to:

Which cleans up to:

The formula for the circumference of a circle. (This first example is trivial to the point of amounting to a tautology.)

Disc Area

Disc Area

Using the radius of a disc, and the circle circumference formula (2πr), we can derive the disc area formula by integrating a series of circles with radii from zero to the disc radius.

Conceptually, we want:

Where C(x) is a presumed function taking a variable and returning the circumference of the circle with radius=x.

We can implement this as:

Using the circle circumference formula and replacing the usual r with x.

The 2π is a constant as far as the integration is concerned, so we can move it out in front:

We calculate the anti-derivative of x (which is ½ x²) and box the integration:

This evaluates to:

(The 2 and ½ cancel each other out.) This cleans up to:

The familiar formula for the area of a disc.

Incidentally, this derivation shows why the formula for the circumference is the derivative of the formula for area (see Volume and Surface Area). It’s because we’re calculating the anti-derivative of that circumference formula.

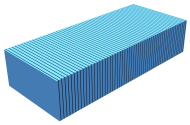

Square Tube Volume

Square Tube Volume

By slicing the tube into vanishingly thin rectangles along one dimension (call it the length), we can integrate the rectangular area along that length. The area of the cross-section rectangle is width × height, the other two dimensions.

Conceptually, we want:

Where A(x) is a presumed function taking a variable and returning the area of the cross section at a given x value.

Since that cross section is the same at all points along the length, we can ignore x and implement this as:

Where wh (width × height) is the rectangular cross section area of the tube (regardless of any x value). This area is a constant as far as the integration is concerned, so we can move it in front:

Now we calculate the anti-derivative of 1 (which is x) and box the integration:

This evaluates to:

Which cleans up to:

The formula for the volume of a rectangular solid (as with the first exercise above, this one is essentially a tautology, but the trivial ones helped me understand the integration basics).

Cylinder Volume 1

Cylinder Volume 1

Using the radius and length of a cylinder, along with the disc area formula (πr²), we can derive the cylinder volume formula by integrating the disc area along the length of the cylinder. This is similar to the square tube example above but for a cylinder.

Conceptually, we want:

Where A(x) is a presumed function that returns the area of the cylinder at point x along its length. As with the square tube, this area is constant all along the length, so x doesn’t matter, and we can implement this using the disc area formula:

Both π and r² are constant as far as the integration is concerned, so we can move them in front:

We calculate the anti-derivative of 1 (which is x) and box the integration:

This evaluates to:

Which cleans up to:

The formula for the volume of a cylinder (this one is essentially the same as the Square Tube exercise above but with a slightly more interesting area formula).

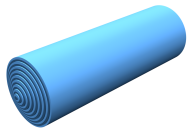

Cylinder Volume 2

Cylinder Volume 2

Using the radius and length of a cylinder, integrating a series of cylinder surfaces with radii from zero to the cylinder radius, we can derive the cylinder volume formula in a different way. The cylinder surface area formula treats the surface as a wrapped rectangle that is length × height, where height is 2πr (the wrapped circumference of the ends of the cylinder).

Conceptually, we want:

Where A(x) is a presumed function that returns the surface area of a cylinder with radius x.

We can implement this as:

Where x is the radius of the sub-cylinder, and l is the cylinder length. The 2π and l are both constant as far as the integration is concerned, so we can move them in front:

We calculate the anti-derivative of x (which is ½ x²) and box the integration:

This evaluates to:

Which cleans up to:

The formula for the volume of a cylinder.

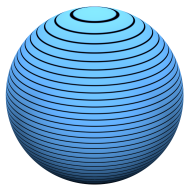

Sphere Volume 1

Sphere Volume 1

Using the radius of a sphere, and the surface area formula (4πr²), we can derive the sphere volume formula by integrating a series of spherical surfaces with radii from zero to the sphere radius.

Conceptually, we want:

Where A(x) is a presumed function taking a variable, x, and returning the surface area of a sphere with radius=x.

We can implement this as:

Using the sphere surface area formula and replacing r with x. The 4π is a constant as far as the integration is concerned, so we can move it in front:

We calculate the anti-derivative of x² (which is ⅓ x³) and box the integration:

This evaluates to:

Which cleans up to:

The formula for the volume of a sphere. (And here again we see the surface area formula being the derivative of the volume formula. This only happens with a few simple shapes.)

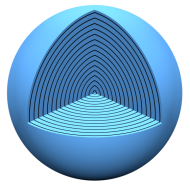

Sphere Volume 2

Sphere Volume 2

Using the radius of a sphere, along with the disc area formula (πr²), we can derive the sphere volume formula by integrating the disc area along a diameter of the sphere.

Conceptually, we want:

Where A(y) is a presumed function that returns the disc area of a slice of the sphere along a diameter scanned from –r to +r (assume this diameter runs from the “south pole” (–r) to the “north pole” (+r).

We need the radius of these disc slices given a y value along the diameter from pole to pole. Since we’re also given r, the radius of the sphere, we can use a version of the Pythagorean formula, x² = r² – y², to determine x, the radius of the disc slice.

We implement this as:

The disc area formula is πr², and since the Pythagorean formula above gives us x², we don’t need to square the terms in the parentheses. The answer they provide (radius squared) is exactly what we want. The pi is a constant as far as the integration is concerned, so we can move it in front:

We calculate the anti-derivative (this is the part that took me a while to get) and box the integration:

Evaluating this is a bit more complicated than the other exercises because the integration runs from –r to +r, whereas the others run from zero to some value. That means the evaluation includes both:

We evaluate the inserted +r and –r terms:

We reduce this to:

And reduce again to:

We need matching fractions, so:

This evaluates to:

Which cleans up to:

The formula for the volume of a sphere.

Cone Volume

Cone Volume

Using the radius and height of a cone, along with the disc area formula (πr²), we can derive the cone volume formula by integrating the disc area along the height of the cone.

Conceptually, we want:

Where A(x) is a presumed function that returns the disc area of a slice of the cone with a given height=x.

We can implement this as:

Where r/h provides a ratio between the cone’s height (h) and the radius (r) of the disc at the cone’s base. (It was this bit that I didn’t figure out myself and had to research.)

The π, r/h are both constant as far as the integration is concerned, so we can move them in front:

We calculate the anti-derivative of x (which is ½ x²) and box the integration:

This evaluates to:

Which cleans up to:

The formula for the volume of a cone.

§ §

That’s all for now. Fun for me, but probably dull reading. Unless maybe, like me, you’re trying to figure out integration for the first time.

Stay integral, my friends! Go forth and spread beauty and light.

∇

July 18th, 2024 at 12:08 pm

I think I’m actually getting integration! Or maybe not.

I recently posted a “mathematical limerick” over on Substack:

Translation:

The old text file I pulled the limerick from claims the math is correct, and the first time I tried it, it seemed to be. But redoing it here for this comment, I get a different answer. Either I don’t get integrals, or the person who made this made a mistake. In fact, the same mistake I did the first time I tried this.

I began by calculating the anti-derivative of z² (which is ⅓ z³) and boxing the integration:

Plug in the end and start values and evaluate:

And here’s where there might be a bug (or an error on my part). The first time, I evaluated the above as:

Which works out nicely, because:

Combined with the integral, we have ⅔ × 0.5 = ⅓. Which is what we need, because that’s what the right side of the equality amounts to:

The problem is that z³ isn’t 3 for (√3)³ but 5.196152… and ⅓ of that is 1.73205…

So, either I’ve got it wrong, or the original author made the same mistake I did.

Anyone out there smart enough to say for sure?

July 21st, 2024 at 12:45 pm

This was answered by a knowledgeable person on Substack. The limerick is not correct. (I was right that it’s wrong.) To make it work, the upper bound must be changed to ³√3 and the second text line to, “From 1 to the cube root of 3.”

One theory is that the formula and text were correct but somewhere along the line the formula got corrupted to just √3 and then someone must have altered the text to fit. That does end up repeating the “cube root” phrase in the second and last lines — “square root” and “cube root” would be nicer, I think.

I do wonder if the original author made the same mistake I did and created the limerick as is.

October 24th, 2024 at 4:31 pm

This is very cool!