Be a Tauist!

I’ve found it extremely difficult to focus this past week. Most of the blame is on Substack Notes, a part of Substack that’s very similar to Twitter or a Facebook feed. I never had Twitter, dumped Facebook ages ago, and barely know what Instagram, Snapchat, et cetera are.

I have no immunity to a doomscrolling feed of interesting micro-posts. Reading them is bad enough. The urge to jump in join the fun is all but irresistible. But days are passing with little to show for them: no books read, no posts worked on, no software projects advanced.

Now it’s Tau Day, and I can’t let that pass postless.

I’ve written plenty about the transcendental pi, as well as Pi Day and Tau Day. I don’t have anything new or interesting to add to that. I will say that my celebration of Tau Day has more to do with my affection for ordering two pizzas (of very different types) than any deep commitment to tau over pi.

Other than numerical pi, the only other kind of pie I love!

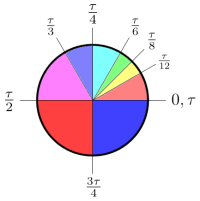

One reason is that I like how the formula for the circumference of a circle, 2πr, is the derivative of formula for its area, πr² [see Volume and Surface Area]. That doesn’t work with tau. That said, the ratio of diameter circle to circumference is better understood in terms of τ. Six of one, half-dozen of the other, dealer’s choice, whatever.

§

Pizza, and pie, and pi (and tau) all put me in a circular frame of mind. We don’t want to go around in circles endlessly, but a good spin once in a while clears the cobwebs. If you know me, you know I can go on for a while in a roundabout way, but I’m trying to turn over a new leaf, so I’ll come round to the point.

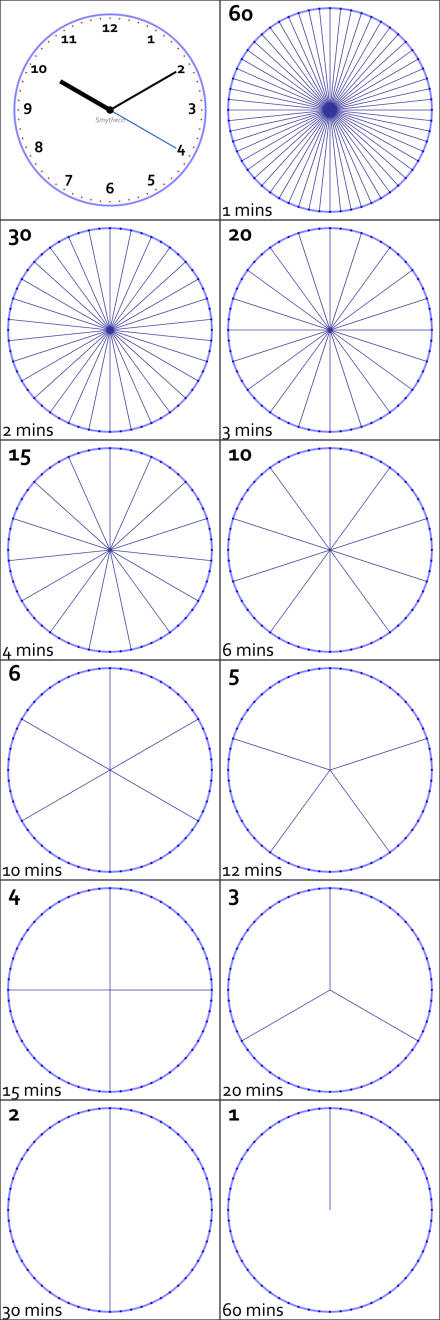

It might seem a bit arbitrary that we divide an hour into sixty minutes. Likewise, each minute into sixty seconds. Why sixty?

Turns out sixty can evenly divided a whole bunch of ways. A pizza divided into sixty slices would offer little more than slivers to sixty people, but they could be combined to equally feed thirty, twenty, fifteen, ten, six, five, four, three, two, or, obviously, just one.

This is because:

And besides the prime factors of two, three, and five, all possible combinations of any of those are also factors. Including one and sixty, there are eleven ways to slice the pie using a basis of sixty divisions — lots of ways to divide an hour into even chunks:

I recall how, when I was a field tech, The Company had us reporting time in tenths of an hour — you might charge 3.3 hours, for instance. It was a bit weird learning to think in six-minute intervals. Never really did get used to it. Or the whole keeping track of my time thing.

§

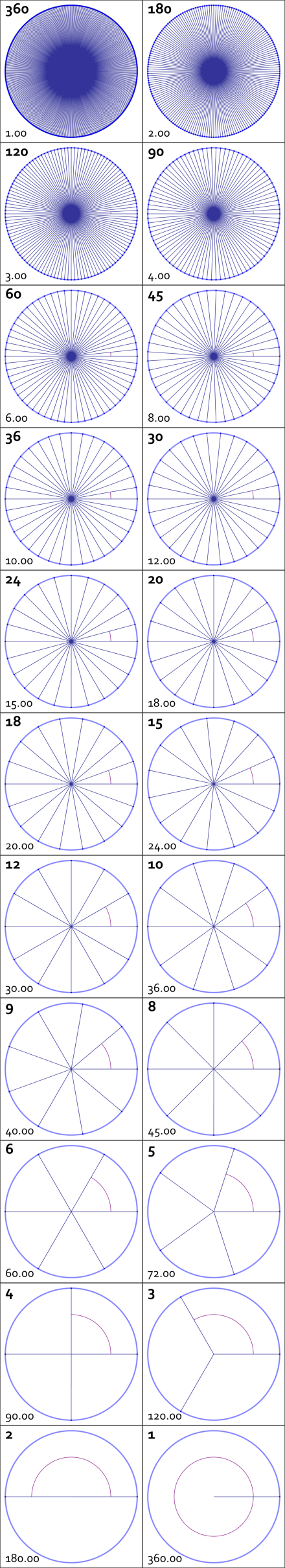

The eleven ways of dividing an hour have nothing on the twenty-two ways of dividing a 360° circle. The idea of dividing a circle into 360 degrees seems, at first, just as arbitrary as dividing hours and minutes into sixty.

There are six prime factors for 360:

Compared to the four for 60, so there are more combinations. Twenty-two, including one and 360.

In fact, degrees of a circle are divided into sixty minutes, and each minute is divided into sixty seconds. The whole sixty thing comes from ancient Babylonian astronomy. If you thought scrolling down the above image was something, get a load of this:

In physics, it’s common to use pi radians rather than degrees, but you don’t get this nice divisibility with pi radians. The circle is 2π radians around, and pi is transcendental, so there’s no apparent, let alone obvious, way to slice the pi.

Now, standby for a spin to something completely different (yet still circular).

§ §

I’ve mentioned the Amazon Prime show Invincible a couple of times but never posted about it in detail. I liked the show at first, but it didn’t wear well with me. Re-watching the first season when the second one came out reminded me more of the things that annoyed me than the things that engaged me. By the end of the second season, I wasn’t much of a fan anymore.

As with Resident Alien, I sought out the comic Invincible is based on, and that made the show even harder to like [in both cases, see Resident Alien]. The comic isn’t great (like Resident Alien was), but it was better than the adaptation. I considered posting about Invincible, too, but decided life was too short.

So, no rant about how much the Invincible adaptation annoyed me. Or why the comic didn’t grab me. (Suffice to say a big part of it is that I’m over superheroes.)

§

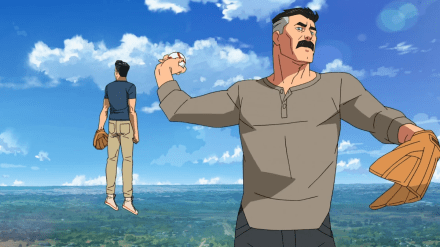

The circular topic I’ve been spiraling up to is a scene that’s in both the comic and TV show. The story involves a superhero, Omni Man, who is essentially Superman — including that he’s from another planet. Omni Man’s secret identity as Nolan Grayson includes an Earthly wife, Debbie, and a son they had together, Mark. The story begins with Mark, a teenager, finally getting the superpowers he inherited from his dad.

Mark follows in his dad’s footsteps as the superhero Invincible. (He’s obviously the main character of the series.) I’m deliberately leaving out some really important info in order to not spoil it.

What you need to know for this is that both Invincible and Omega Man can fly like Superman. They also have Superman-like super-strength. In this scene they’re playing catch — with a baseball — while hovering high in the air. The catch is that they’re back-to-back and throwing the ball around the world.

I’m not trying to be a spoilsport here. This is not just science fiction, but a graphic novel (slash animated TV show) about superheroes, so we’re fairly far into the speculative fantasy side of SF. Hard science fiction this ain’t.

That aside, it’s fun (at least for a mind like mine) to think about what they’re suggesting here (and whether there is a shred of reality to it — the short answer: no way in hell).

Because the editing of the TV show, not to mention the snapshot nature of graphic novels, makes it impossible to get a strong sense of the time involved — how long each is waiting for the ball to circle the Earth and return to their position. The implication from the flow of dialogue is that not much time is involved.

In fact, the flow suggests no more than two or three minutes, but I’ll use five minutes as a maximum. It’s more than enough to demonstrate the problem.

I’m forced to make some other assumptions. I can only guess how high Mark and Nolan are from the scenery behind them. It’s definitely several thousand feet. Another assumption — that they are throwing the ball in a circular orbit — necessitates that they are high enough for the ball to miss the tallest mountain along its path.

They’re necessarily throwing the ball in a great circle, but they can orient that circle in any direction. Some paths would offer lower obstacles than others. At the extreme, the path that intersects Mount Everest requires over 29,000 feet coverage. Clearly, they’re not that high here so we have to assume they found an orbit with everything well enough below, let’s say, 10,000 feet. And that, therefore, is the altitude Mark and Nolan are at.

That’s less than two miles, so it doesn’t add much to the Earth’s 3,959-mile mean radius. We’ll keep it pretty and round up to 4,000 miles. Then (here comes more pi):

So, Mark and his dad are tossing the ball a distance of over twenty-five thousand miles. Strong arms! Given the distance, and making an assumption about time, we can derive the speed of the ball. If we assume it only takes two minutes:

Which is astonishingly fast. It’s over one percent of one percent (0.112%) of light speed (670,616,424 MPH). Giving them three minutes doesn’t slow things down significantly:

Still pretty blazing fast — 0.075% lightspeed. Giving them a whole five minutes gets them down to less than half of the two-minute speed, but still:

It’s a lot — 0.045% lightspeed.

The baseball wouldn’t survive those speeds in any kind of atmosphere. The friction would quickly burn it up. Alternately, air resistance would slow it down in a hurry and it would fall to Earth.

There is also the matter of orbital speed. Even the five-minute “orbit” wouldn’t. The escape velocity of the Earth is just a hair over 25,000 MPH. Throw a baseball at that speed, and assuming it survived, it would head off into space.

Orbital speed, by the way, gives us one last occurrence of pi:

Where a is the length of the semimajor axis in meters and T is the orbital period.

§

My whole point being that the scene looks cool but — to anyone versed in the simple science involved — instant and obvious bullshit.

And that was a key objection I had to Invincible (and a lot of other media). All the instantly apparent obvious bullshit indicating extremely weak science backgrounds from people writing what purports to be a kind of hard science fiction.

And at its core it’s just one more example of a new term I heard and can’t get out of my head: “social entropy”. The breaking down of a once more organized and effective social system. The growth of ignorance and fantasy over knowledge and fact.

Yeah, it’s just a stupid superhero comic, but it and so many similar examples speak volumes to me about where we are compared to where we were.

§ §

Last night’s debate spoke even louder, but that’s gist for another mill.

Stay orbiting, my friends! Go forth and spread beauty and light.

∇

June 28th, 2024 at 7:39 pm

It is, by the way, eleven years to the day since I walked out of work for the last time. Retirement Anniversary! (And, man, do I love being retired!!)

June 29th, 2024 at 8:45 am

And today would have been my mom’s 100th birthday!

June 28th, 2024 at 7:43 pm

WTF? Now the WordPress Reader leaves that pointless sidebar up even while reading posts? WordPress, you continue to make this place worse and worse. No wonder people are leaving, and no wonder I’m thinking more and more I will, too.

June 28th, 2024 at 7:54 pm

Hahaha…Substack Notes got you in the end! I wonder if the ad-free environment had something to do with it?

June 29th, 2024 at 8:49 am

I definitely need tear myself away more reliably. Too many days have gone by with not enough productivity to show for them, and it’s starting to bug me. Just have to get used to and a bit bored with the new toy. I can say that, if there had been ads in the feed, it would never have been attractive to me. Definitely a huge selling point.

June 29th, 2024 at 9:44 am

What orb would be a reasonable replacement for Earth, given super human strength and an atmosphere there or not?

June 29th, 2024 at 10:55 am

I tried to use the formulas for orbital speed and orbital period, but am obviously getting something wrong, because I’m getting nonsensical answers (and I’m not even clear on what the units are supposed to be — kilometers or meters? and no clue on time units).

I’m no orbital mechanic, but I do know orbital speed (and thus period) depends on the mass of the body being orbited and the radius of the orbit. More mass, faster orbit. Bigger radius, slower orbit. So, I’m wild-ass-guessing that a small, massive body might have enough gravity for a quick orbit around a small circumference. The bigger the body, the slower the minimum orbital speed… 🤷🏼♂️

I found an online orbital calculator, but I’m not sure I trust the results. If I select “Earth” I get one answer, but if I select “Other” and plug in the Earth’s mass and radius, I get a different answer. But using the preselects, going through the Solar System, I was surprised that the close orbital periods were all in the 80-200 minutes range (Saturn being an outlier with a 251-minute orbit). What varied hugely was the orbital speed.

I’ve long wanted to know more about orbital mechanics. I’ll have to dig into it someday…

July 3rd, 2024 at 5:39 pm

Okay, I got the orbital mechanics formulas working (see below).

If we assume Mark and Nolan are at 10,000 feet (3,048 meters), their ball has an orbital radius of 6,374,000 meters. This requires an orbital period of 5064 seconds (84 minutes) and a velocity of 7,904 km/s (17,680 MPH). But the speeds calculated for an orbit as long as five minutes result in a speed of over 300,000 MPH. (Which is escape velocity and then some.)

So, if they were waiting almost 90 minutes between toss and catch, it would almost work, but air resistance makes it impossible anyway.

One answer your question is that, for a two-minute orbit around an Earth mass, they need an orbital radius of 526 km. Which would put them almost at the Earth’s core. But if there were a small, very dense body with Earth’s mass and a radius of, say, 400 km, or thereabouts, then they could play catch with a two-minute delay.

July 4th, 2024 at 9:58 am

That’s what I was hoping you’d design. An airless, dense mass around which a “moon” might orbit with a period acceptable to a pair of players playing catch with said moon.

July 4th, 2024 at 7:39 pm

Had a bit more fun with speculation. The smaller the mass, the lower the orbit. It was just easy with what I had at that point to plug in the two-minute period and get a radius assuming the Earth’s mass. But I did a run where I reduce that mass iteratively, and the two-minute orbital radius drops:

As a reference point, the mass of Mount Everest (according to one interweb source I checked) is about 8.1×10¹⁴, so the last rows are for a mass about that size. Those close orbits wouldn’t work unless the body was dense and small. Everest is almost nine kilometers tall. So, big factor here is density of the body being orbited. I suspect you could play a very fast game of catch around a very small black hole. I should do the calculation with increasing mass!

June 29th, 2024 at 9:51 am

This reminds me of the whole space elevator nonsense. So many bad assumptions with that proposal.

If we’d had 12 fingers and 12 toes I wonder if that would have made our development as an industrial and technically advanced species any easier?

June 29th, 2024 at 11:00 am

Hard to say. One number base is the same as any other number base, numbers are numbers regardless of how we spell them. Twelve (prime factors: 2×2×3; other factors: 4 & 6) isn’t hugely better than ten (factors: 2×5; no other factors). Four factors versus two.

Things could have gone the other way, as in so many cartoons. Four fingers and base eight!

July 3rd, 2024 at 4:53 pm

Below are some important formulas for orbital mechanics. Distances should be in meters, mass in kilograms, and time in seconds.

Orbital Period

The orbital period is how long a single orbit takes.

Where a is the orbit’s semi-major axis, G is the gravitational constant, and M is the more massive body (usually the body being orbited).

Inversely, to find the distance for an orbit given its period:

Using all the same variables as above.

Orbital Speed

The orbital speed is the average speed of the orbiting body. It can be determined from the orbital radius and period.

Where a and T are, as above, the orbital radius and period, respectively.

The orbital speed can also be determined with the radius and mass of the larger body:

The values of G and M can be hard to determine precisely, but apparently their product, GM, is not.

July 3rd, 2024 at 5:17 pm

Some orbital data:

Importantly, note the theoretical surface orbit, which imagines an orbit at ground-level. It’s immediately obvious that the speed is just a bit faster than the low end of a LEO. This has important implications for a supposed game of world-circling catch at any altitude up to LEO.

July 3rd, 2024 at 5:41 pm

Here’s some Python code implementing the four formulas (plus two others):

002|

003| def SurfaceGravity (mass, radius):

004| p = G * mass

005| q = pow(radius, 2)

006| return p/q

007|

008| def EscapeVelocity (mass, distance):

009| p = 2 * G * mass

010| q = distance

011| return sqrt(p/q)

012|

013| def OrbitalSpeed (mass, a):

014| p = G * mass

015| q = a

016| return sqrt(p/q)

017|

018| def OrbitalPeriod (mass, a):

019| p = pow(a, 3)

020| q = G * mass

021| return 2 * pi * sqrt(p/q)

022|

023| def OrbitalSpeed2 (a, period):

024| p = 2 * pi * a

025| q = period

026| return p/q

027|

028| def OrbitalDistance (mass, period):

029| p = G * mass * pow(period, 2)

030| q = 4 * pow(pi, 2)

031| return pow(p/q, 1/3)

032|

July 21st, 2024 at 12:40 pm

[…] on Tau Day (which is also my retirement anniversary), I posted about a scene in the superhero comic Invincible that involves a baseball orbiting the Earth at a […]