It’s happy hour and you and a friend go out for drinks. The bar is serving a new drink that catches your eye, and you both order one. They’re served in martini glasses (which are upside down hollow cones) and look quite tasty (see picture).

It’s happy hour and you and a friend go out for drinks. The bar is serving a new drink that catches your eye, and you both order one. They’re served in martini glasses (which are upside down hollow cones) and look quite tasty (see picture).

More to the point here, the glasses look acceptably full. Not a lot of “headroom” between the top of the drink and the top of the glass. Your friend, a mathematician, bets you they can pour all of your drink into their glass without spilling a drop.

Should you take that bet?

Well, firstly, it’s probably not wise to bet against a mathematician. At least not in any bet involving numbers or math or geometry. In this case, you will lose the bet, because cones are deceptive.

Let me lay out the bet in more detail. We start with two drinks in conical martini glasses:

If we measure the height of the liquid (which is identical in each glass — the bartender is a robot), we’d find that it comes up to 78% of the total height of the fillable inside of the glass. Which means the remaining 22% is the empty headspace between the top of the liquid and the top of the glass.

If we look edge-on, the glasses look like this:

Your friend bets you that the contents of your glass will fit into theirs without spilling a drop. And without first removing any liquid from either glass. The bet is that the contents of both glasses — as they are right now — fit into one glass.

Prima facie, this seems like a bet you can’t lose. How is it possible the contents of your glass can fit into the remaining headspace of your friend’s glass? And yet, as I’ve already said, this is a losing bet.

Your friend picks up your glass and carefully pours it into theirs:

Without spilling or stealing a drop. Seen from the side:

These aren’t trick glasses. The quick bottom line is that the volume of a cone is deceptive. And that martini glasses are a big win for bars. A conical glass that looks just over 75% full is, in fact, holding only half of its possible volume (specifically, 47.5% of the total volume of a completely full glass).

Even if the glass is 90% full (in terms of the height of the liquid), it still only contains 73% percent of the total possible volume. That last 10% of headspace still comprises over a quarter of it.

Half full or half empty?

Only when the glass is 99% full by height does its volume reach what we’d consider truly full: 97.0% (with the missing 3% in that 1% of headspace).

Going the other direction, a glass that’s 50% full by height contains a mere 12.5% of the total volume of the cone.

(So, if anyone ever brings you a half-full martini, you can be pretty sure they were sipping from it on the way. And at least this glass looks like it’s missing something.)

So, that’s the punchline. Cone-shaped glasses fool you. Because cone volume is sneaky.

That’s it for today (I thought it made a good Wednesday Wow). If you’d like to know a bit more about what’s going on here, keep reading. There’s some math, but I’ll throw in a chart to make it pretty.

§

Let’s start with the formula for the volume of a cone:

Where V is the volume, r is the radius of the base, and h is the height from base to point. Note that this assumes the cone isn’t truncated — the point isn’t cut off — and is fully symmetrical — the point is directly above the center. In other words, a basic no-frills cone.

We’re interested in a sub-cone that shares the apex with the main cone, and is the same shape as the main cone, but which has a height that’s some percentage of the total height. In the supposedly full happy hour drinks above, the percentage of the sub-cone was 78%.

We’re interested in a sub-cone that shares the apex with the main cone, and is the same shape as the main cone, but which has a height that’s some percentage of the total height. In the supposedly full happy hour drinks above, the percentage of the sub-cone was 78%.

Because the two cones are identical except for their height (and therefore the radius of their bases), the ratio between the two heights is the same as the ratio between the radius of two bases. So, if the height of the sub-cone is 50% of the main cone, then its radius is also 50% of the main radius.

We can adjust the volume formula to account for a sub-cone of a cone with a given radius and height:

Where s is the ratio of the sub-cone’s height to the main cone’s height. We use this to calculate the ratio of volume in the sub-cone to the main cone (which, unlike radius, is not linear).

First, though, we have to calculate the volume of an entirely full drink. We’ll assume a radius of 1.5 and a height of 2.0:

The result above shows an answer in cubic units. These can be inches, millimeters, feet, or even miles. Whatever we’re using, we have a total volume of 4.7 cubic units.

The happy hour drinks were filled to a height of 78% (0.78), so:

Only 2.2 cubic units of drink. Less than half of 4.7 — just 47.5% of that total volume. Cones will fool you.

[Note that we could have used this adjusted formula to calculate the total volume using s=1.0, which reduces to the original volume formula.]

We can also calculate the volume of a sub-cone that’s 50% as high as the main cone — a glass that’s, depending on your point of view, half full or half empty:

You are not reading that wrong. Only 0.6 cubic units, a paltry 12.5% of the total volume, which is why the glass looks pretty empty despite being “half full” (because it’s actually nowhere near).

Have I mentioned that cones are sneaky?

§

Changing the radius and/or the height changes the volume numbers — more volume or less volume — but does not change the ratio of volume between the sub-cone and the main cone. Regardless of the shape of the glass, if it’s full to 78% of its height, that is always only 47.5% of the total volume of the glass.

For example, a tall thin glass with a radius of only 0.8 but a height of 2.5 has a total volume of just 1.47 cubic units and a 78% full volume of 0.70 cubic units. Which is still 47.5% of the total possible volume.

Alternately, a wide short glass with a radius of 2.5 and a height of only 0.5 has a total volume of a whopping 3.27 cubic units and a 78% full volume of 1.55 cubic units. And again, that’s 47.5% of the total volume.

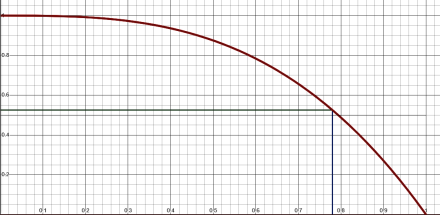

The red curve on the graph above shows the headspace of a cone compared to its sub-cone. The graph is normalized and represents any cone and sub-cone. The horizontal axis is the ratio of the height of the sub-cone to the main cone. Zero, at the left, is no sub-cone, and 1.0, on the right, is a sub-cone the same size as the main cone. The vertical axis is the amount of headspace from zero (none) to 1.0 (all headspace).

The dark blue vertical line marks 78% percent height. It meets the red curve just above the 0.5 horizontal indicating the volume of the headspace here is slightly more than 50% — and it is: 52.5% (which is 100% – 47.5%). The key point is that the headspace doesn’t really get small until the sub-cone is at least 90% of the main cone’s height.

Cones. Are. Sneaky. (Must be their pointy heads.)

In contrast, an ordinary cylindrical glass is straightforward. If it’s apparently half-full, it’s actually half-full. Likewise, if it’s visually 78% full, it’s actually 78% full.

§ §

As an aside, calling martini glasses “upside down hollow cones” does assume that cones do, in fact, have a right-side-up and that it is the pointy bit. But we do refer to the base of a cone. And given the difficulty of balancing a top-heavy cone on its point, it’s not a sight we see often (science fiction kinda likes it for that reason — unusual looking).

Also, volcanoes.

Stay conic, my friends! Go forth and spread beauty and light.

∇

June 5th, 2024 at 6:58 pm

Geordie looks at martini glasses as though they were the stupidest thing humans ever invented, and he’s right.

June 5th, 2024 at 7:09 pm

Smart little guy! He must be a secret mathematician.

June 6th, 2024 at 10:58 am

Keep in mind that the following would be trivial for any college (if not high school) calculus student, but I didn’t take any calculus until I took two corporate-sponsored adult education classes back in the 1990s. They only covered the basics and derivatives, so I never learned integration. This is the first integration problem I tried to solve on my own. I failed, but got close and, more importantly, finally find how it works it sinking in.

I wanted to see if I could figure out how to derive the volume formula for a cone by integration. The basic idea is to think of splitting the cone into a stack of infinitely thin discs. The radius of these starts at zero at the cone’s peak and increases linearly down the cone’s height to its base (where the disc radius is the radius of the cone’s base). Each disk is infinitely thin, so it has no volume, but does have an area (πr²). The volume of the cone would be the sum of the areas of all the disks. There are an infinite number of disks, so we need to integrate over them. Conceptually, we want something like:

Which integrates the πr² area of each disk over the height (h) of the cone. However, this version only works if r=x, which requires that r=h. This also doesn’t account for exactly how we set the problem up. Which is to imagine the cone oriented horizontally with its peak at the origin (0,0) and extending along the positive x-axis. The base of the cone is at x=h. (See this diagram.) The slope of the cone here is r/h, and this relates the radius to x. Now we can write a useable integration formula:

We can immediately pull out the constant pi out in front and separate the inner terms:

In this context we can also treat the radius and height as constants and pull them out in front:

And this even I can integrate (it’s almost the simplest possible example of integration):

Which evaluates to:

Throw a little algebra at it, and we end up with:

The formula for the volume of a cone.

I tried to solve this on my own, but eventually had to go ogle it. I was very close — essentially got the inner formula — but didn’t know where to take it next. Perhaps it was this attempt to solve it on my own, but after a lot of attempts, the lesson may finally have stuck. Nice to know I can still learn in my late 60s!

June 10th, 2024 at 11:23 am

I think I figured out how to get the formula for the area of a disc via integration on my own:

Which uses the circumference of a circle, 2πr, and integrates the area of a disc as an infinite set of circle circumferences from zero radius to r, the radius of the disc. In the above, x stands in for r, and the constants, 2π, have been pulled out of the integration. The anti-derivative is simple, giving us:

The formula for the area of a disc!

June 10th, 2024 at 11:33 am

And this seems to derive the formula for the volume of a cylinder using integration:

Which uses the area of a disc (derived in the previous comment) and integrates that the volume of a cylinder as an infinite set of disc areas from zero to h, the height of the cylinder. The constants, π and r² have been pulled out and put in front. The anti-derivative of one is x, so we have:

The formula for the volume of a cylinder.

I think I’m starting to get this, but my grasp seems tenuous still.

July 15th, 2024 at 1:06 pm

[…] story begins with the Cones Can Fool You! post last month, which was about the beguiling volume of cone-shaped glasses. Central to that post […]