Earlier this year, I posted about that math gag that seems to prove (very mathematically) that 2=0 (an alternate version “proves” 1=0 using the same trick: a covert division by zero, an operation whose undefined result breaks the chain of logic).

Earlier this year, I posted about that math gag that seems to prove (very mathematically) that 2=0 (an alternate version “proves” 1=0 using the same trick: a covert division by zero, an operation whose undefined result breaks the chain of logic).

Today I’m posting about another somewhat common mathematical (or rather, geometrical) gag — one involving chocolate! In the form of a magical chocolate bar that lets us remove an infinite number of bite-sized pieces but somehow remains the same size. It seems impossible.

And of course, it is. In this post I reveal the magician’s trick!

Common sense (backed by physics) tells us that removing a piece of chocolate from a chocolate bar necessarily reduces the amount of chocolate in the bar by exactly the size of the removed piece. There’s no rearranging of the pieces that makes the bar whole again — allowing infinite repetition of removing and rearranging. Obviously, there’s a trick here.

And there is. There always is with magic and magicians. The wonder, at least for some, isn’t in the putative magic but in the delight of the mechanics of the trick. It’s a matter of how clever the design and deception are.

On its surface, the gag is pretty simple. We have a magic chocolate bar — or rather, a triangular half of a magical chocolate bar:

The bar has been conveniently divided into different sections, ‘A’ through ‘E’ — the last one, a single square (highlighted in yellow in Figure 1).

The gag is that we can remove the ‘E’ piece, enjoy our bite of chocolate, and then rearrange the remaining four pieces like this:

Giving us the same sized bar we started with. Remove that single piece again, enjoy eating it, and again rearrange the bar to restore it to previous size. Repeat until full (or sick of chocolate).

Obviously, there’s a trick here, some unseen sleight of hand. But what?

§

The first thing we might try is adding up the areas implied by each piece and seeing how that compares to the area implied by the whole (triangular half-) bar.

The formula for a triangle’s area is one-half the product of its height and width because any triangle can be inscribed in a rectangle:

Figure 3. The area of a triangle is one-half the area of the rectangle containing it because it occupies exactly half that rectangle.

The product of height and width gives us the area of the rectangle exactly containing the triangle. View Figure 3 as having two blue triangles (joined by the dotted red line) to see how each matches the yellow area adjacent to it. The yellow and blue triangles on the left are the same, and so are the two smaller ones on the right.

Armed with that simple formula, we know that the chocolate bar triangle, which is five squares high and thirteen squares long, has:

Looking at the individual pieces, the ‘E’ piece is easy: one square. The ‘C’ piece has eight, and the ‘D’ piece has seven. These three sum to 16, which is readily apparent in the 2×8 rectangle they form in Figure 1.

The larger ‘A’ triangle has ½(3×8)=12 squares, and the smaller ‘B’ triangle has ½(2×5)=5 squares. Together, the two triangles have 17 squares.

Which adds up to 33 squares — an extra half-square compared to the 32.5 square area of a 5×13 triangle. And if we subtract the ‘E’ piece’s one-square contribution (by eating it), the four remaining pieces sum to 32 squares, which is a half-square short of comprising a 5×13 triangle.

So, something’s definitely rotten in our proverbial Denmark.

§

We can zero in on the problem by focusing on the three triangles, the main 5×13 one and the two it contains, 3×8 and 2×5. The ‘C’, ‘D’, and ‘E’ pieces, being rectangular, don’t easily allow sneaky tricks, so the “magic” must be in the triangles.

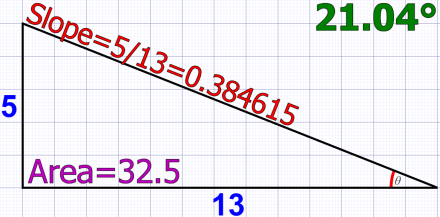

Figure 4. Area, slope, and angle of the main triangle.

The simplest thing to examine (even simpler than area) is the slope. All three triangles are similarly oriented right triangles that, as presented, should have identical slopes (because ‘A’ and ‘B’ share the slope of the main one).

Slope is just “rise over run” (or y over x), and those are the very (and only) numbers we are given for each of the three triangles. Figure 4, which examines the main 5×13 triangle, shows its slope to be 5/13 or 0.384615.

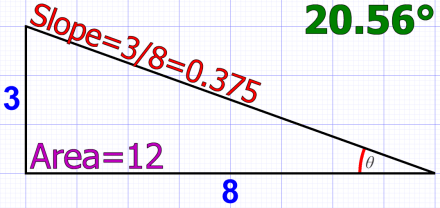

Figure 5. Area, slope, and angle of triangle ‘A’.

Already it’s apparent something is up, because we know the slopes of the two inner triangles are not 5/13. The ‘A’ triangle, with 3×8 squares, obviously has a slope of 3/8 (0.375), and the ‘B’ triangle, with 2×5 squares, equally obviously has a slope of 2/5 (0.400).

Figure 6. Area, slope, and angle of triangle ‘B’.

If we normalize the fractions for a common denominator (of 520), we have:

Which shows that the slopes are close, 195 versus 200 versus 208, but definitely not the same. The ‘A’ and ‘B’ triangles can’t fit exactly inside the main triangle because the slopes don’t match. (We could equally have compared the decimal values: 0.375 versus 0.384615 versus 0.400.)

As a final confirmation, using the slope with the inverse tangent (trigonometry) function gives us the angle (of the angle on the right, the one labeled θ (theta). Those angle values, shown in each of the three figures above (in green), also show the mismatch between the three triangles: 20.56° versus 21.04° versus 21.80°.

§

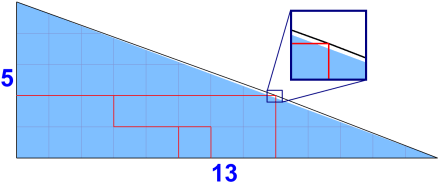

In Figure 1 and Figure 2, what appears to be the straight-line diagonal of the triangle is actually the two ever-so-slightly different diagonals of the respective ‘A’ and ‘B’ triangles. Since they have nearly the same slope, but varying in opposite directions, the overall diagonal appears straight.

A more precise drawing of the initial configuration makes this clear:

Figure 7. Revealing where the extra area comes from!

The blue shaded area is the actual 5×13 triangle, the black outline shows the cheat. Because the black lines meet the red lines (shown magnified in the insert) the ‘A’ and ‘B’ triangles are, as advertised, 3×8 and 2×5 respectively.

But if we drew the main triangle accurately, those two red lines protrude outside:

Figure 8: Why the main triangle (32.5 squares) is too small.

Which means triangles ‘A’ and ‘B’ are not 3×8 and 2×5 (respectively), but something just slightly less.

As noted above, the five-piece ensemble has 33 squares, whereas the triangular chocolate bar, drawn accurately, has only 32.5 squares. So, the gag is that we don’t draw it accurately. We draw the cheat revealed in Figure 7.

The reassembled (four-piece) chocolate bar triangle has, by piece count, 32 squares, which means it has a half-square less than an accurately drawn 5×13 bar. In this case, the cheat works the opposite way:

Figure 9. Revealing where the missing area goes!

The blue shaded area, as above, is the accurately drawn 5×13 triangle. Here the accurately drawn ‘A’ and ‘B’ triangles (which have swapped places) cause the apparent main diagonal to notch inwards, slicing off a shred of area — enough to add up to half a square.

If we drew the triangle accurately, there would be an open space where the red lines don’t meet the (now straight) black line:

Figure 10: Why the main triangle (32.5 squares) is too big.

In this case, the ‘A’ and ‘B’ triangles are bigger than they should be (and overlap).

So, the gag is that the straight line of the diagonal isn’t straight but just slightly kinked in both the five-piece and four-piece versions. First, kinked outwards, then kinked inwards. Because the first version has 33 squares and the second has 32, they’re both visually close to the 32.5 squares of the 5×13 triangle.

I think part of what makes this work so well is that both the 33- and 32-square versions error equally (by a half-square) but oppositely from what they are both represented to be. The first one is just a tiny bit too big, the second one an equally tiny bit too small. The only way to spot the difference is to put a straightedge along the diagonal.

Or compare the two with a blink test:

Or, as always, do the math!

§ §

Here the trickery was misrepresentation, a triangle that isn’t what it appears to be. In the depths of math, however, is the Banach-Tarski paradox, which isn’t a gag but a demonstration of the problem of real numbers. The Banach-Tarski paradox features a way to disassemble a solid ball into pieces and then reassemble those pieces into two solid balls, each with the same size as the original.

It’s a genuine conundrum. One that raises a question about just how real the real numbers actually are. It raises the great bumper sticker question about whether reality is rational but not real.

Stay chocolate, my friends! Go forth and spread beauty and light.

∇

May 7th, 2024 at 8:45 pm

With summer approaching, I’ve been wondering if I’ll be plagued by wasps in the house again (as I was last summer). I really got to wondering when I spotted one outside the bedroom window last week. A few days later, I found one in the house, in the usual place (but still no clue where they’re coming from).

None since but seeing one this early in the season has me creeped out a little. Is it going to get worse as things get warm? Just wish I knew where they were lurking!

May 7th, 2024 at 11:43 pm

Thanks for this. I could never figure that one out.

May 8th, 2024 at 10:34 am

You’re quite welcome. I’m glad someone found some value in one of my math posts!

May 8th, 2024 at 8:04 pm

Brilliant! I always wondered how that could work. And why it wasn’t what it appeared to be.

May 8th, 2024 at 10:14 pm

Thanks, now you know! A tiny matter of a 1.25° kink in a line — impossible to spot.

May 9th, 2024 at 2:32 am

His name is “Tarski”, not “Tarsky”. (An awesome logician.)

May 9th, 2024 at 3:35 pm

Ah, oops! Fixed, thanks! (I also get name-confused by the V.I. Warshawski books written by Sara Paretsky.)

May 9th, 2024 at 3:37 am

By the way, the Banach-Tarski paradox gives a way to chop a ball into finitely many pieces and rearrange those to form 2 balls each of the same size.

May 9th, 2024 at 3:44 pm

It’s not surprising I got this wrong (fixed now) — I don’t get the Banach-Tarski paradox despite some videos trying to explain it. I seem to lack the math fundamentals necessary. I think I was misled by a line in the Wikipedia page lede, “However, the pieces themselves are not ‘solids’ in the usual sense, but infinite scatterings of points.” Apparently, it’s the pieces that have something infinite about them.

I recall seeing the Banach–Tarski paradox mentioned in connection with the Axiom of Choice, which I’ve also struggled to understand (and may have given me the idea of infinite sets, apparently the context where the AoC becomes significant).

May 10th, 2024 at 10:20 am

Yes, in the Banach-Tarski paradox we chop a ball into finitely many pieces and reassemble these into two balls, but these pieces are “nonmeasurable”: they don’t have well-defined volume! That’s necessary, or else we couldn’t reassemble them into a set that has twice the volume of the original ball. We can only prove the existence of nonmeasurable sets using the Axiom of Choice. In simple terms this means there’s no way to concretely describe a specific nonmeasurable set, because defining a nonmeasurable set requires making infinitely many choices, and there is no way to concretely specify how we will make each one of these choices. The Axiom of Choice asserts that there is a way to make these choices, but doesn’t tell us how to make them.

In general the Axiom of Choice says that whenever you have an infinite collection of choices to make, there is some way to make all those choices. Logicians of the early 20th century, trying to clarify the foundations of mathematics, found that the Axiom of Choice is required to prove many desirable theorems, yet it also has consequences that shake our confidence in it. The Banach-Tarski “paradox”, not strictly a paradox, is a great example of the counterintuitive results that follow from the Axiom of Choice.

A deep dive into axiomatic set theory would be required to be really precise here.

May 11th, 2024 at 9:13 am

From the accounts I’ve seen (not that I’ve pursued this vigorously), it seems a topic that gets abstract and deep right off the starting block. Thanks for taking the time to write back!

As unreliable as intuition is, let me see if mine is anywhere in the vicinity. Say you have a set where each member is an open interval between two adjacent natural numbers: {(0,1), (1,2), (2,3),…} So, all the positive reals excluding the integers. If we wanted to make a subset with one number from each interval, then we’d need a way to pick that number in each interval. But we can’t use smallest or largest, because those intervals don’t have those properties. So, is the issue picking a selection function for a set of sets when the member sets may not lend themselves to such a function? But the AoC says there always is such a way? Or am I pitching way outside the zone?

In the case I described, one could use the average of the end points, so: {0.5, 1.5, 2.5,…}

May 11th, 2024 at 12:11 pm

You are indeed describing a situation where we could use the axiom of choice. You have an infinite collection of nonempty sets and you are trying to choose an element of each one. The axiom of choice guarantees you can do it. But you don’t need the axiom of choice here, because you can give a perfectly systematic procedure to do it: just choose the midpoint of each interval! The reason you can give this procedure the sets are described in a concrete manner that makes it easy to describe elements of them.

The axiom of choice would become important if instead you described your sets more abstractly. For example, suppose I tell you only that I have nonempty sets X₁, X₂, X₃, … You know that each set Xi has a member, because I told you so. But how do you know that there’s a sequence (x₁,x₂,x₃, ….) where each xi is an element of Xi? Now you need the axiom of choice! I’m not giving you enough information to describe a specific element of each set Xi. You need some axiom – some principle – that guarantees that because each set Xi is nonempty, there exists a sequence (x₁,x₂,x₃, ….) where each xi is an element of Xi. And this is the axiom of choice!

To be precise, for this task we only need a rather wimpy version of the axiom of choice, called the axiom of countable choice, because you are only making a countably infinite number of choices! The axiom of choice really comes into its own when we have to make an uncountable number of choices. But the idea is exactly the same.

May 11th, 2024 at 2:24 pm

Oh, thank you, I think the lightbulb may have just gone on. Let me see if I have this now:

The AoC is just the assertion that there always exists a sequence (x₁, x₂, x₃,…) — and this sequence always contains at least one member. (But perhaps only one?)

Therefore, given an abstract set of non-empty sets and a requirement to pick one member from each, one can assert the AoC and then say just take the first item from the sequence.

It’s like the Excluded Middle in asserting an axiom that ground other assertions. I know if something is not False, it must be True. I know I can always pick one item from each member set even without a concrete description of the sets.

If that’s right, I may have been over-thinking it. Intuitively, it does seem “obvious” that, given any set of bins, you can always reach into each and grab the first item you touch. But describing that formally does seem to require a formal definition of the bins.

May 11th, 2024 at 4:30 pm

I don’t know what it means for a sequence to contain a member: it’s sets that have members, not sequences, and the whole clause “this sequence always contains a member” is unnecessary. The axiom of countable choice says exactly this:

Suppose we have nonempty sets X₁, X₂, X₃, … Then there exists a sequence (x₁,x₂,x₃, ….) where each xi is an element of Xi.

Indeed, the axiom of choice is meant to capture something intuitively obvious. But as you probably realize, since “reach into each set and grab the first item you touch” is not math, we need an axiom to make precise our intuition that this is something we could (in principle) do, no matter how many nonempty sets we are given.

May 11th, 2024 at 5:52 pm

Ah, I had a misunderstanding. You’re saying that each xi corresponds to an Xi. I mistook the idea as each Xi having its own sequence of at least one item (so there would be as many sequences as member sets Xn).

But if xi maps to Xi then the AoC really does seem clear to me. I somehow thought there was more to it than the simple assertion that, given a set of non-empty sets, you can always make a sequence consisting of one member from each set. So, I’m guessing the fun for mathematicians is coming up with member sets for which the AoC fails?

May 12th, 2024 at 5:37 am

You keep using math terminology in a way that distresses me, but I guess that’s just the lot of a mathematician: we use language like a scalpel, and any wrong move could kill the patient. I wouldn’t say xi “maps to” Xi. Each Xi is a nonempty set, and the axiom of countable choice asserts that there is a sequence (x₁,x₂,x₃, ….) where each xi is a “member of” Xi, or – another way to say the same thing – each xi is an “element of” Xi.

But it sounds like you get the idea. The axiom of countable choice is meant to be blitheringly obvious. Nonetheless it is “nonconstructive”: it gives no procedure to find the desired sequence (x₁,x₂,x₃, ….), nor does it even give us a specific such sequence: it merely asserts that some such sequence exists! There are a lot of mathematicians who have decided that nonconstructive math is problematic. One reason is that it leads to strange results like the Banach-Tarski paradox. But there’s a lot more to the story. There was a huge battle over the axiom of choice in the early 20th century. Now many mathematicians realize that it’s pointless to argue about whether axioms of this sort are “true” or “false”; it’s better to explore both alternatives and see where they lead. Now with the rise of computers more mathematicians are embracing constructive math, since it’s closer to what can be implemented on a computer.

May 12th, 2024 at 12:59 pm

Sorry! 😊 My formal math training, quite some time ago, ended at early calculus — derivatives of polynomials. But I’ve encountered so much math in my hobbies and interests that I’ve been working on learning more. One big goal is getting a good grasp of the math of quantum mechanics (one of my long-time interests). Obviously, I still have a great deal to learn. And let me say I appreciate you spending time on my backwater blog helping me learn a little bit more. Thanks!

Funny thing: I stumbled a little over the word “map” in my previous reply. I know it has specific meaning to mathematicians and wasn’t positive it applied here. I think it was the indexing by i that felt like a mapping to me, but perhaps a mere correspondence doesn’t qualify. I’m a retired software designer, and I’ve long thought one good metaphor for writing software is writing a novel — a novel not only with a sensible (useful) plot and correct logic throughout, but also with perfect spelling and grammar. So, I totally get precision and the distress caused by others missing what seem clearly visible easy targets. And it always raises that social conundrum of silently going with the flow or speaking out in hope of education and growth. For the record, I’m firmly in the latter group and am grateful when others help me learn and grow. (So, thanks again!)

I have some sympathy for intuitionism and constructivism. I like the Kronecker quote, “God made the integers, all else is the work of man.” There may be something to it. (I suspect you dropped by because I linked to your series about problems with the reals?) Perhaps the reals are our idealizations of the physical world just as circles are idealizations of real-world circles but can never physically exist. I don’t know if everyone has a line where they go, “Now, that’s just some made up stuff!” but for me it’s transfinite numbers. I’m okay with uncountable infinity being bigger than a countable one, but I draw the line at games with different uncountable infinities. But it occurs to me that, to you, that may seem as naive as people I’ve met who draw the line at complex numbers. Which seem perfectly “natural” to me.

“One person’s ‘Duh!’ is another person’s ‘Huh?'”

May 13th, 2024 at 2:04 am

Yes, I dropped by because you linked to a post of mine.

It’s rather hard to “draw the line” at different uncountable infinities once you’ve accepted Cantor’s rather simple argument that the number of subsets of a set must be larger than its number of elements. You can accept this and only accept the existence of finite sets, but once you admit a single infinite set this argument shows there must be larger and larger infinite sets, going on forever. I know mathematicians who deny Cantor’s argument and only accept a single infinity, the countable one. But I’ve never heard of a mathematician who accepts two infinities – a countable one and an uncountable one – and stops there!

Of course one can also “draw the line”, not by disbelieving Cantor’s diagonal argument, but simply by losing interest in larger infinities – i..e., treating them as not very interesting. That’s my usual attitude: most of math I pursue never uses them. For years I avoided learning more than the basics. But then I realized it was silly for me to actively avoid learning a branch of math, so I spent some studying larger infinities. The subject definitely has a certain addictive charm (like many subjects). It’s just not very relevant to most of what I’m interested in.

May 13th, 2024 at 9:46 am

Heh, not the first time I’ve linked to your continuum series. It’s one of my “Keeper” links (so is your Crackpot index page — a vital resource). I’ve been following your blog for years because, although it often gets over my head, I learn a lot from what I can follow. I also appreciate how mathematically eclectic it is. Takes me to foreign math places I didn’t know existed!

I think “losing interest” is perhaps a better way to put it, although I still wonder about invention/discovery distinction when it comes to non-physical infinity. Merely countable infinity leads to the Hilbert Hotel, so we’re already firmly in Abstractlandia. I do get the powerset argument, and I see your point about how it forces you to accept all those alephs and omegas, but don’t find it meaningful because it’s abstraction upon abstraction. Definitely Kronecker’s “work of man” territory and, like string theory, I don’t see how it applies to anything interesting.

The distinction between countable and uncountable infinity, though, fascinates me. So do the conundrums of the real numbers. (Which is why I so took to your continuum series.)

May 11th, 2024 at 4:57 pm

I was curious to see if I could account for the difference between the 5×13 triangle and the misrepresentation the gag depends on. I wondered if I could calculate the “shaved off” parts of triangles A and B. And, yep, it was pretty easy.

Refering to Figure 7 in the post and note the difference between the blue-shaded triangle — the true 5×13 triangle — and the outline in black (which isn’t really a triangle but a polygon with four sides). The outlined “triangle” has 33 squares while the blue-shaded one has 32.5 squares.

The difference lies in the slivers along the A and B triangles and in the tiny corner that protrudes. Note the white space in the tip of that corner. That space isn’t part of the 32.5 squares of the blue triangle.

The B triangle is simple, the slope (of the blue triangle) times the length of the base gives us the rise to the peak:

Which, ah ha, isn’t quite the expected value of 2. This triangle only rises to 1.923, which makes it smaller than the advertised 2×5 triangle. The width is still exactly 5, but the height is less.

The A triangle is ever so slightly more complicated because this time we want to know the (truncated) base length. We can’t use the basic rise-over-run formula, we need the run-over-rise (to calculate how long the triangle’s base is). So, we invert the 5×13 slope (effectively rotating triangle A by 90°) and use the height as the multiplier:

Which, again, isn’t the expected value of 8. The smaller version — the one limited by the 5×13 blue triangle — only has a base of 7.8, so again smaller than the advertised 3×8 triangle. This time the height remains the same, 3, while the width is less.

Now that we have accurate width and height data, the area is easy to calculate:

Exactly 11.7 (compared to the expected 12 for triangle A). And the B triangle’s area:

Compared to the expected 5 squares.

Keeping things rational for precision, the total area of the legit 5×13 triangle by adding the two triangles (whose area we’ve just calculated) plus the 2×8 rectangular block (pieces C, D, and E in the post’s Figure 1:

Adding the 16 squares of the rectangle gives us 32.5-and-change, which, huh, isn’t the expected answer of exactly 32.5. Is that and-change a math error?

Ah, but we forgot that corner of the rectangle that sticks up beyond the blue-shaded space! We know its outside point is (8,2) because that’s the rectangle’s size. Since its other points are points of triangles A and B — points we just calculated, we have the coordinates necessary to calculate its area:

Which is exactly the extra area from the previous calculation. Mystery solved!

May 11th, 2024 at 6:30 pm

I was also curious to see if I could account for the difference between the 5×13 triangle and the second misrepresentation — the one in the post’s Figure 2. I wondered if I could again reconcile the numbers.

Refer to the post’s Figure 9 and note the difference between the blue-shaded triangle — the true 5×13 triangle — and the outline in black (which isn’t really a triangle but a polygon with four sides). The outlined “triangle” has 32 squares while the blue-shaded one has 32.5 squares.

The difference lies in the slivers along the A and B triangles. And note how the upper right corner of the 3×5 rectangle (outlined in red) falls short of the edge of the blue-shade boundary. Importantly, note how — per the blue shaded area — the lower-right tip of triangle B overlaps with the upper-left tip of triangle A.

The A triangle is simple, the slope (of the blue triangle) times the length of the base gives us the rise to the peak:

Which, of course, isn’t the expected value of 3. This triangle rises to 3.077, which makes it bigger than the advertised 3×8 triangle. The width remains exactly 8, but the height is greater.

As above we invert the 5×13 slope to rotate the B triangle so we can calculate the run-over-rise (the length of the base):

Where we were expecting just 5. Given the slope of the 5×13 triangle, this triangle should be larger. This time the height remains the same, 2, while the width is less.

Now we can calculate the area of triangle A:

More than the expected 12. And the area of B:

Again more than the expected 5 squares.

Keeping things rational for precision, the total area of the legit 5×13 triangle by adding the two triangles (whose area we’ve just calculated) plus the 3×5 rectangular block (pieces C and D in the post’s Figure 2:

Adding the 15 squares of the rectangle gives us 32.5-and-change, and the and-change looks familiar (see above).

This time, however, it comes from the overlap of triangles A and B. We can include the full area of one triangle but not both. The amount of the overlap must be deducted.

The upper right corner of the rectangle (red lines) again forms one point of the triangle we need to calculate. The other two, as before, are the triangle’s points we calculated above. So (and this should look familiar because it’s the inverse of above):

Which is exactly the extra area from the previous calculation. Mystery again solved!

June 21st, 2025 at 3:58 pm

[…] functional and decorative elements. Be aware that slight variations in angles or slopes can create visual illusions when sections are rearranged, similar to the principle behind certain chocolate bar […]