I love the complex numbers (see all these posts). They’re the simple but magical awesome sauce of mathematics. (The general notion of an imaginary axis also underlies the quaternions and octonions.) This page is dedicated to my love of complex numbers…

I love the complex numbers (see all these posts). They’re the simple but magical awesome sauce of mathematics. (The general notion of an imaginary axis also underlies the quaternions and octonions.) This page is dedicated to my love of complex numbers…

The Imaginary Unit

It all begins with the imaginary unit, the notorious i, famously the square root of -1. Called “imaginary” because — according to grade school math — the square of a number is always positive, so there is no way to square a number and get -1.

But it turns out that math is broken without it [see Easy Complex Numbers and “Imaginary” Numbers (also: “Imaginary” Parabola)].

We need i to make the fundamental theorem of algebra true — that all polynomials have at least one root. It’s necessary for solving something as simple as x²+1 = 0. It pops right out when we rearrange that to x² = -1 and take the square root of both sides: x = √-1.

The magic of complex numbers comes from the fact that i² = -1. (That magic, and a bit more, applies also to the just mentioned quaternions and octonions. See Quaternions for an introduction.)

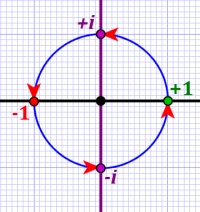

If we start with i² = i×i = -1, we can derive i³ = i×i×i = -1×i = –i and then i⁴ = i×i×i×i = -1×-1 = +1.

If we start with i² = i×i = -1, we can derive i³ = i×i×i = -1×i = –i and then i⁴ = i×i×i×i = -1×-1 = +1.

Note that this brings us back to where we started (because all multiplications implicitly begin at unity (i.e. one).

Using this strategy, we can derive a pattern for the powers of i:

This is our first indication that multiplication by complex numbers is the same as rotation (on the complex plane).

We can also derive the powers of negative i:

Which, of course, is different from:

Now the pattern goes:

Now the rotation goes backwards (clockwise). These patterns make sense when we view multiplication by i as a 90° rotation (and by –i as a -90° rotation, although it’s actually a positive rotation by 270° — rotation is canonically measured counterclockwise from the positive X axis).

Equating multiplication with rotation comes into fruition in the next section. For now, note that -1 represents two 90° rotations — 180° total. Associating -1 with a 180° rotation explains why, with regular numbers, multiplying a positive number by a negative number results in a negative number. Multiplication by a negative number rotates the positive number 180° to the negative axis.

More importantly, it explains why multiplying two negative numbers results in a positive number. With two negative numbers, there are two 180° rotations — 360° total, and that rotates back to the positive axis. [See Numbers Gotta Number for an in-depth look.]

Lastly, note that:

Because:

The Complex Plane

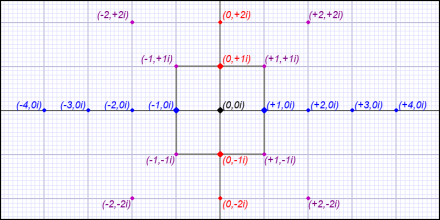

If we multiply any real number times i, we get an imaginary number.

Examples: 0i (aka 0), 2i, 3.1415i, -5i, 0.5i, and so on for any xi.

This implies an axis of such numbers — the imaginary axis — that is a copy of the real axis with its values multiplied by i. Because we see that multiplication as a 90° (counterclockwise) rotation, we orient this imaginary axis 90° (orthogonally) to the real number axis, intersecting it at their mutual zero points:

The real axis (blue) and imaginary axis (red) together form the complex number plane. The eight purple numbers are complex numbers (points) on that plane (so are the red and blues ones).

Two orthogonal axes with real coordinates form a Cartesian plane, variously called the Wessel, Argand, Gauss, or just complex plane. (The other names refer to mathematicians who explored the properties of complex numbers.)

Terminology: There is the imaginary unit, the imaginary numbers, and the imaginary axis. These are respectively analogous to the real number one (the real unit), the real numbers, and the real number axis. Combining a number from the real axis with one from the imaginary axis gives us a complex number — a single point on the complex plane.

The orthogonal imaginary axis inspired Carl Gauss to refer to the complex numbers as the “lateral” numbers — probably a better name than “imaginary” because there’s nothing imaginary about them.

A complex number are single points on the complex plane. They are therefore inherently two-dimensional (making them very useful in 2D geometry) but at the same time are indivisible components with two parts: a real part and an imaginary part. [See The Complex Plane for more.]

One thing that makes complex numbers different from the natural numbers, the integer numbers, and the rational numbers is that there is no sort order for the complex numbers. There’s no clear, obvious way to say one is “less than” another. This is generally characteristic of points on a surface and to some extent to uncountability.

Complex Number Forms

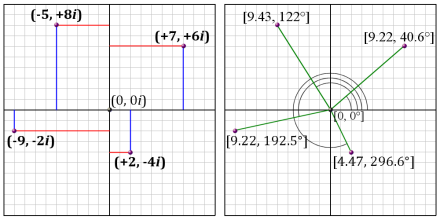

There are a number of different ways to represent complex numbers:

These divide into two basic groups, rectangular (or Cartesian) versus angular (or polar). Both require two numbers (because complex numbers are inherently two-dimensional). Cartesian coordinates use values from the real and imaginary axes. Polar coordinates use an angle (counterclockwise from the positive X axis) and a radius (or distance from the origin).

Two basic ways of representing complex numbers, rectangular (left) and angular (right). Because they are related through trigonometry, whole values in one form equate to messier values in the other.

Note that, regardless of how expressed, all complex numbers have an angle and a distance. These are called, in different contexts, the argument (or angle or phase) and the magnitude (or absolute value or radius). Here I will try to use angle and magnitude.

Taking the above forms from left to right:

First: z is the shorthand form. The form is abstract and neither rectangular nor angular. It’s convenient when developing or analyzing equations that use complex numbers. Obviously, actual calculations (usually) require the actual real and imaginary values (but there are some exceptions).

Second: a+bi is the standard or canonical form. The a and b are real number coordinates on the real and imaginary axes, so this is a rectangular form. The imaginary unit makes bi an imaginary number. The plus-sign between the terms emphasizes that a complex number is considered a single value. (But because the two terms come from orthogonal axes, the addition can never actually be calculated, and the sum always remains a two-term expression.)

Third: [x, y] is the pure Cartesian form. The comma and square brackets make this look like the 2D coordinate it actually is. This form is more common when using complex numbers for graphics because the x and y map directly to the display plane. It ignores the imaginary unit because graphics only cares about the real coordinates.

Fourth: [r, θ] is the polar coordinate form somewhat analogous to the Cartesian form in being straight-up 2D (no imaginary unit) but based on the distance (radius, hence the r) and angle theta (θ). The angle is measured counterclockwise from the positive real axis, which is 0° (so the positive imaginary axis is 90°, the negative real axis is 180°, and the negative imaginary axis is 270°. An angle of 360° (or any multiple of it) returns to the positive real axis.

Fifth: r·(cos θ, i·sin θ), is the Euler form. It shows the relationship between the rectangular and angular forms. In fact, it’s an expression that converts the angle and radius to the canonical (a, bi) form. To convert the other way:

Sixth: r·eiθ is the exponential form. It may look a bit exotic at first but turns out to be another angular form. It’s the other half of what’s called Euler’s Formula:

Which converts between the Euler and exponential forms. That formula also leads to a lovely bit of math known as Euler’s Identity:

[See the Beautiful Math post for details.]

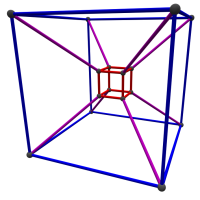

A complex number also has two matrix representations:

The first is the rectangular version; the second is the angular version. You may recognize the second version as a rotation matrix [see the Rotation Matrices page for more information]. This dual matrix representation illustrates how rotation and complex numbers are intimately connected.

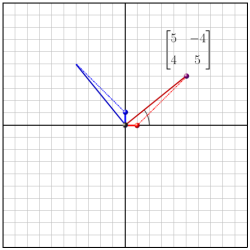

As a rotation matrix, the complex number matrix form represents a rotation (and scaling) of the complex point at 1.0+0i (i.e. the real number one) to the desired complex point. For example, the matrix that represents the complex point 5+4i is:

This rotates the complex number 1.0+oi to the complex number 5+4i:

The matrix transformation for 5+4i.

The matrix for 5+4i has two column vectors, i-hat [5, 4] and j-hat [-4, 5]. These transform the basis vectors x-hat [1, 0] and y-hat [0, 1] to [5, 4] and [-4, 5] respectively. [This is a standard linear algebra rotation/scaling. See Matrix Magic for more.]

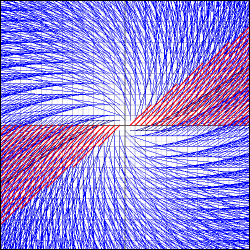

This (and multiplication by all complex numbers) rotates and scales all the coordinates (except the origin) in the space:

Transformation of the complex plane under the rotation/scaling described by the above matrix.

Complex Number Operations

We can perform operations with complex numbers similar to those used with scalar numbers (like real numbers and integers). We can add, subtract, multiply, divide, and exponentiate. There are some additional operations available for complex numbers, such as conjugate.

Complex Addition

Adding two complex numbers together just adds their respective real and imaginary parts. In canonical form:

Addition is messy in the angular forms. It’s usually easiest to convert to rectangular form where adding is easy. As an example:

Or in exponential form:

But in rectangular form it’s simply:

Addition using angular forms requires using the law of cosines to determine the new magnitude and the law of sines to determine the new angle.

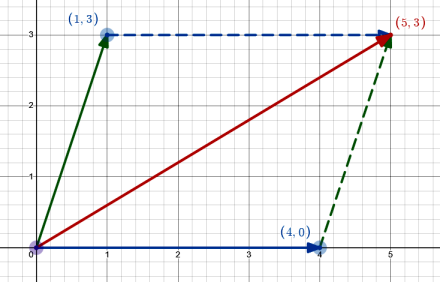

In fact, because complex numbers inhabit a plane and be interpreted as vectors, addition has a geometric definition sometimes called the parallelogram rule because of the shape created by the two vectors and translations of each to the tip of the other:

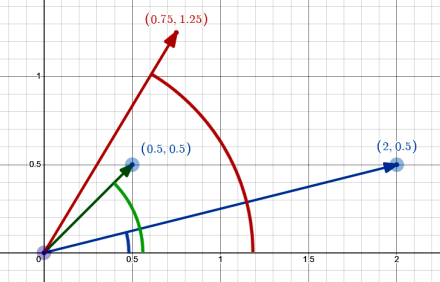

Note how the blue vector is copied to the tip of the green vector and vice versa. The sum is where the copied vectors meet (the red vector).

Complex Multiplication

Multiplication is a tiny bit harder:

But easier (and cleaner) in polar form:

Or exponential form:

Multiplication also has a geometric definition — the magnitudes multiply and the angles add. It is because the angles add that multiplication of complex numbers is rotation. Each complex multiplicand has an angle, and the product angle is the sum of those:

The angle of the red product vector is the sum of the blue and green vector angles. The magnitude is their product.

Here are some illustrative examples of multiplication of some basic values:

Put symbolically: 1×z=z. The complex number (1+0i) is the multiplicative identity in the complex numbers.

And minus one acts as we’d expect:

Put symbolically: –1×z=-z. Note this rotates z by 180°.

Suppose we multiply by i:

Note how the a and b terms swapped positions and that b is negated. This effectively rotates z by 90° (counterclockwise).

If we multiply by minus i:

Then z is rotated minus 90° (that is, clockwise).

Lastly, consider this one:

Which I’ll let you work out for yourself. What’s significant is that since squaring the left side gives us (0+i) — or just i — on the right side, the left side is the square root of i (√i).

In case anyone ever asks.

Complex Conjugate

Complex numbers have a complex conjugate:

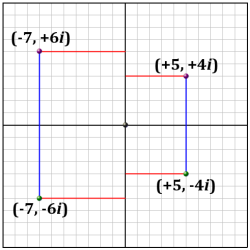

(The trailing star indicates the complex conjugate.) We create the conjugate by reversing the sign of the imaginary part. As such, the complex conjugate is a reflection across the real axis:

The two complex numbers on the left are complex conjugates of each other. So are the two on the right. Note how each pair is reflected across the X axis.

Multiplying a complex number by its conjugate results in a real number:

The square root of that value is the complex number’s magnitude. This is one case where we can use the shorthand form usefully:

The |z| notation means the “absolute value” of z, which for complex numbers is their magnitude. The shorthand notation makes the conjugate form more obvious: z* versus z. Compare that to:

There are two useful identities we can depict easily in shorthand form:

Adding a complex number to its conjugate (and dividing by two) gives the real part of z. On the other hand, subtracting its conjugate (and dividing by two) gives the imaginary part of z. These identities come from the more general:

The last two work because adding a conjugate vanishes the imaginary part (because it’s negated) whereas subtracting vanishes the real part but in subtracting the sign-reversed imaginary part, ends up adding it.

Cartesian Product

We can take the Cartesian product of two complex numbers:

We get the same four terms as when multiplying (because multiplying essentially is taking the Cartesian product). And because multiplication commutes, so does the Cartesian product. It doesn’t matter which number is where.

Outer Product

Rather fancifully, if we plug complex numbers into Dirac Bra-Ket notation, we can consider the outer product operation |x〉〈y|. This is similar to the Cartesian product but requires the use of the conjugate for the second number. In this, the ket |x〉 is a two-part column vector, and the bra 〈y| is a two-part row vector with conjugate values:

The outer product does not commute (the magic of complex number conjugates):

The two result matrices are similar but not identical. They are conjugate transposes of each other. Note that these matrices do not represent single complex numbers — not all 2D matrices do, only those that follow the form described above. (Because they contain imaginary values, they can be considered operators on a 2D Hilbert space.)

If we take the outer product of the same complex number:

We get a matrix where the sum of the four terms is a² + b² (because abi – abi = 0). This is what we’d expect when we multiply a complex number by its own conjugate — the magnitude squared.

Inner Product

Continuing down the silly rabbit hole, we can use the same Bra-Ket trick to consider the inner product 〈x|y〉 (which, in this case, requires that the bra 〈x| to be the conjugate row vector and the ket |y〉 to be the column vector:

As usual with an inner product, the result is a scalar — a single value, not a matrix. Taking the inner product of the same number reveals something familiar:

This is the same magnitude-squared value we get by multiplying a complex number and its conjugate (which is exactly what’s happening here). The two operations differ in that the inner product vanishes if the two numbers are orthogonal, whereas ab* does not.

Note that the a+bi form is similar to the general polynomial: rx³+sx²+tx¹+ux⁰. form in that the powers of x are incompatible with addition, so the polynomial — despite having plus signs — can never be summed. Likewise, a complex number can never be summed because the two parts, a and bi, are incompatible with addition.

As an aside, the similarity to polynomials is more apparent with quaternions, which have the form a+bi+cj+dk, where a, b, c, d are real numbers and i, j, k are all distinct imaginary units. As incompatible as powers of x in polynomials.

The point is that separate terms cannot be combined and must stand alone.

Ø

And what do you think?