The previous post, Our Memories, suggested that — in large part because they become faded self-imaginings— we might want to consider not clinging to our event memories as much as we sometimes do. We might want to focus on what we are more than where we’ve been.

The previous post, Our Memories, suggested that — in large part because they become faded self-imaginings— we might want to consider not clinging to our event memories as much as we sometimes do. We might want to focus on what we are more than where we’ve been.

Put it this way: What matters is what you are (and can do), not what facts or moments you can recall. Which is likely why I always resisted memorizing dates or formulas I can easily look up.

Which touches indirectly on a counterpoint to what I wrote yesterday…

A key reason I’ve long resisted learning factoids is the perception that they are readily available. Why burden oneself with details that must first be memorized and then likely later refreshed. Even when I was a student back in the Pliocene one could find these things in books. Now looking up a date or formula is trivial.

Consider, for instance, the formula for the volume of a sphere:

Not that hard to remember, especially if used with regularity, but still a specific detail to be memorized.

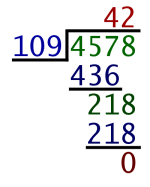

In contrast, consider the process of long division we learned in grade school.

In contrast, consider the process of long division we learned in grade school.

[Alternately, we could compare memorizing the trigonometry identities with learning how to drive or ride a bike.]

There is a (I think fairly big) difference between remembering factoids and learning a process. As they say, “You never forget how to ride a bike.”

What they don’t say is: you never forget the date of the War of 1812 or who’s buried in Grant’s Tomb.

Okay, maybe those were bad examples, but I think you take my point. And as the Wiki links show, even if one is as confused as a trump voter, those things are still easy to look up.

§

Along with a natural resistance to factoid memorization — perhaps driven by my seriously stunted details and events memory — is a quote from a Sherlock Holmes story that grabbed me at a young age (grade school).

The bit is in A Study in Scarlet (1887), the first Holmes/Watson story ever published. It starts with Watson’s stunned shock when Sherlock reveals he neither known nor cares whether the Earth revolves around the Sun or vice versa:

My surprise reached a climax, however, when I found incidentally that he was ignorant of the Copernican Theory and of the composition of the Solar System. That any civilized human being in this nineteenth century should not be aware that the earth travelled round the sun appeared to be to me such an extraordinary fact that I could hardly realize it.

(I wonder if Watson’s perceptions still ring true in the 21st century. I no longer trust us all to be on the same page when it comes to physical facts, especially ones with no bearing on most people’s lives.)

Sherlock — to me memorably — replies:

“You see,” he explained, “I consider that a man’s brain originally is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose. A fool takes in all the lumber of every sort that he comes across, so that the knowledge which might be useful to him gets crowded out, or at best is jumbled up with a lot of other things so that he has a difficulty in laying his hands upon it. Now the skilful workman is very careful indeed as to what he takes into his brain-attic. He will have nothing but the tools which may help him in doing his work, but of these he has a large assortment, and all in the most perfect order. It is a mistake to think that that little room has elastic walls and can distend to any extent. Depend upon it there comes a time when for every addition of knowledge you forget something that you knew before. It is of the highest importance, therefore, not to have useless facts elbowing out the useful ones.”

So, why clutter the “attic” with factoids we can always and easily look up? The important thing is our knowledge and acquired skills right now, and to Sherlock’s point, those should be useful in whatever it is we do in life.

But this is just repeating what I wrote yesterday and not my point.

My point, as I said, is counterpoint.

Our Highly Documented Lives

One of the many things different in our modern culture is the way we document ourselves, those around us, and the things that happen in our lives. Just about everyone carries with them, not just a camera, but a video camera. And one of increasingly good quality.

[My dog Samantha (1994-2004) predated digital cameras (at least for me), and in consequence I have only about a dozen photos of her. Actually, there are more, but black dogs are hard to photograph, especially against white snow. My pal Bentley on the other hand, is one highly documented dog. On my personal website, I have a Bentley photo page with over 500 images and constantly growing. There are also over a dozen videos. And I’ve written about here a lot here and on Substack (#dogstack). She will never has to fade in our memories.]

So, we no longer need to rely on only our memories or our notes. Looking up factoids is easier than ever these days, and so is recording our memories.

This changes the dynamic of what I wrote about yesterday. We can now refresh our event memories fairly accurately by viewing the video (or even pictures) of the event.

That said, I recently came across some pre-cellphone digital camera pictures I took of a company luncheon event (Nov 28, 2007):

And while I recognized many faces — certainly those of the people that were co-worker friends back then — my memory of the event is through a very dark glass. Even some of the names are gone, though I remember the face.

Oddly, one thing I do remember clearly is ordering hot apple ciders (with cinnamon sticks in them), a winter phase I went through back then. I think it may stand out because I’m not one for hot beverages. Won’t touch hot cocoa (chocolate is a solid, damn it, so even chocolate soda repels me), never drink coffee (ever), and only occasionally drink hot tea.

Being actually into hot cider was unusual and probably why I remember it. But any conversations I had, or things that happened, or even what the event was for? Gone. (And I’m okay with that.)

Likewise, I sometimes stumble over some pre-cellphone digital camera photos a friend took that time we saw Little Feat at the Medina Ballroom (1999 or so? — I don’t recall):

What I do recall is having a very good time but really only one specific. They were doing Dixie Chicken, and — having heard it many times — I got up to visit the rest room and get another beer. Because lines, it was about 20 minutes before I got back to my seat (as you see, our table was right up against the stage).

And they were still jamming on Dixie Chicken. In fact, by that point, they’d taken it to where it no longer sounded like Dixie Chicken, so when they brought it back home, it was like, “Oh, yeah, right, they started playing that 25 minutes ago.”

I do love a good jam band. I was never much of a musician, but I did develop some ability to jam, and it’s a rush.

Bottom line, perhaps all this documentation of our lives doesn’t mean as much as it seems to. How often do we go back and actually look at old photos or videos and relive those moments? I took a bunch of photos and some video at the Peter Gabriel concert in October of 2023. Other than a few times shortly after, I haven’t looked at them since (see the linked post for those photos). Does having so many of them make them harder to revisit?

Or maybe it’s just me and my sense to leave the past behind.

I do wonder if memories of events become even less memorable when we’re busy filming it. Is the act of capturing a digital memory a distraction from actually living the event and forming a memory? Does the low effort required and the sheer number of pictures and videos devalue them?

I also wonder if, in abdicating our memories to our phones, are we losing the ability to remember anything at all? For those born before, say, 1990, how many phone numbers did you carry around in your head? How many do you carry now?

A while back, while out shopping, I was embarrassed by having to enter my home (landline) phone number… and couldn’t remember it. Had to look it up on my phone. Granted, that number is one I almost never have to recall — in fact, I don’t even answer my landline anymore. It’s always robots. My friends call my cellphone. Or rather, text my cellphone.

[Which is nice because I don’t like the interruption and distraction of a phone call.]

So, assuming it isn’t just me, maybe we’re in a weird place where our lives are indeed highly documented but our memories may be getting so bad that even that doesn’t help as much as we might think. And all that documentation might not amount to as much as we hoped.

There are some tech-heads who’ve undertaken using technology to document every second of their lives. Yet what will that ultimately amount to but more ignored bits in a vast and rapidly growing sea of data?

§ §

Stay documenting, my friends! Go forth and spread beauty and light.

∇

August 14th, 2025 at 4:26 pm

I’m moving- to a much smaller space. I have 150 framed pictures- photos, paintings etc. All of which memories are attached. Maybe I have room for only 30 in the new space. Some are 50/80 years old. I can, of course, rotate them.

“Out of sight, out of mind..?

You bring up interesting points. Thanks

August 15th, 2025 at 11:46 am

You’re welcome.

One thing you might consider is buying one or more of those digital picture frames and then scan your photos to load into them. Then you can have them all in a much smaller space and can even easily add new ones.